Cryptanalysts

Part 1: Breaking Codes to Stop Crime

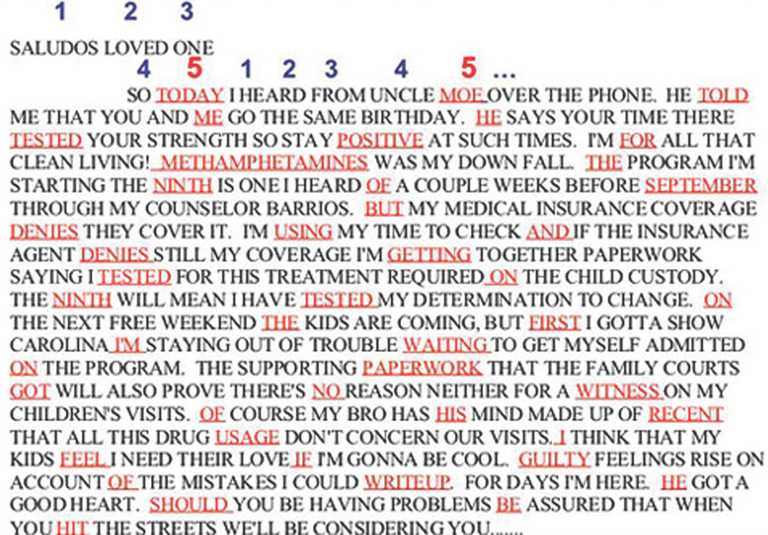

The letter from a gang member in prison to a friend on the outside seemed normal enough. “Saludos loved one,” it began, and went on to describe the perils of drug use and the inmate’s upcoming visit from his children.

But closer inspection by examiners in our Cryptanalysis and Racketeering Records Unit (CRRU) revealed that this seemingly ordinary letter was encoded with a much more sinister message: every fifth word contained the letter’s true intent, which was to green-light the murder of a fellow gang member.

Breaking such codes is CRRU’s unique specialty. Despite the FBI’s extensive use of state-of-the-art computer technology to gather intelligence, examine evidence, and help solve crimes, the need to manually break “pen and paper” codes remains a valuable—and necessary—weapon in the Bureau’s investigative arsenal.

That’s because criminals who use cryptography—codes, ciphers, and concealed messages—are more numerous than one might expect. Terrorists, gang members, inmates, drug dealers, violent lone offenders, and organized crime groups involved in gambling and prostitution use letters, numbers, symbols, and even invisible ink to encode messages in an attempt to hide illegal activity.

Breaker, Breaker

Breaking any code involves four basic steps:

1. Determining the language used;

2. Determining the system used;

3. Reconstructing the key; and

4. Reconstructing the plaintext.

Consider this cipher: Nffu nf bu uif qbsl bu oppo.

Now apply the four steps:

1. Determining the language allows you to compare the cipher text to the suspected language. Our cryptanalysts usually start with English.

2. Determining the system: Is this cipher using rearranged words, replaced words, or perhaps letter substitution? In this case, it’s letter substitution.

3. Reconstructing the key: This step answers the question of how the code maker changed the letters. In our example, every character shifted one letter to the right in the alphabet.

4. Reconstructing the plaintext: By applying the key from the previous step, you now have a solution: Meet me at the park at noon.

Bookies, pimps, and drug traffickers, for example, all keep records of their dealings, explained Dan Olson, chief of CRRU, which is part of the FBI Laboratory. “If there is money and credit involved in a transaction,” Olson said, “there has to be an accounting of that at every step of the way, even if it’s on a match pack, hotel stationary, or the back of a cocktail napkin.”

The unit’s forensic examiners are often tasked with decoding encrypted evidence after subjects have been arrested. But CRRU also plays an important role in thwarting crime by intercepting coded messages—like the prison letter above—particularly among inmates and gang members. “We solve crimes,” Olson said, “but we actually prevent more crimes than we solve.”

The art of breaking codes is an “old-fashioned battle of the minds” between code makers and code breakers, Olson added, explaining that CRRU is the only law enforcement unit anywhere that deals exclusively with manual—as opposed to digital—code breaking.

“We would love to find our counterparts somewhere in the world,” he said, “but so far we haven’t been able to. No one seems to have the niche that we have.”

Becoming a cryptanalyst requires a basic four-month training course and plenty of continuing education to learn the age-old patterns and techniques of code makers. Olson insists that almost anyone can learn basic code-breaking skills (see sidebar), but certain personality types seem best suited to the job, including those who like solving puzzles and who are determined and tenacious.

The unit’s examiners include linguists, mathematicians, and former law enforcement officers like Debra O’Donnell, who worked drug and gang cases in New Jersey before joining the Bureau. “This is very rewarding work,” O’Donnell said, “but you have to have the right temperament for it, because you can’t break every code.”

Still, since World War II, when Bureau cryptanalysts were responsible for cracking Nazi spy codes, CRRU has been getting results—not only for FBI cases but also for local, state, and federal investigators who request our training and assistance.

“We’ve evolved with the crime trends over the years,” Olson said, “but at the same time we’ve kept our previous missions. As long as there are criminals,” he added, ”there will be a need for cryptanalysts.”

Part 2: Helps us crack a code in an open murder case.

Resources:

- More about the Cryptanalysis and Racketeering Records Unit

- Try your hand at code breaking