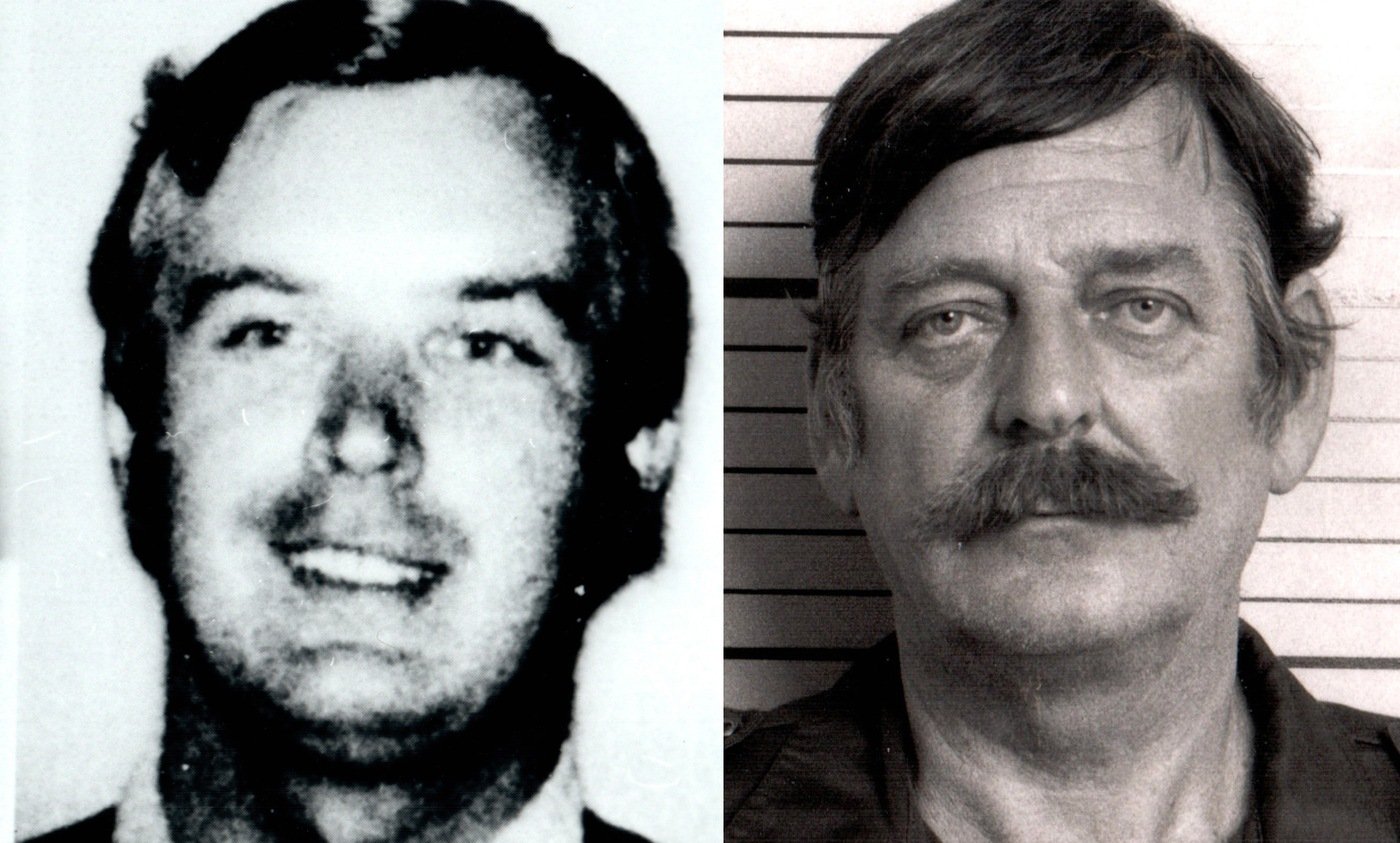

Marian Zacharski was young, charming, and handsome. In his mid-20s, he was a sales rep and rising star in the U.S. operations of the Polish American Machinery Corporation and was living a leisurely life in the suburbs of Los Angeles in the late 1970s.

He was also a spy.

Zacharski was an “illegal”—a foreign intelligence agent living on U.S. soil, operating undercover and unknown to American authorities, much like the Russian spies arrested by the FBI in 2010 that partly inspired the television drama The Americans.

In 1977, Zacharski was sent to California by the Polish government, then an Eastern bloc country working in concert with the Soviet Union, to uncover military and industrial secrets in the aerospace industry.

It wasn’t long before Zacharski found an ideal target.

His name was William Holden Bell. A longtime engineer at Hughes Aircraft Company—an aerospace and defense firm founded by Howard Hughes in 1932—the nearly 60-year-old Bell had a security clearance and access to vital classified information. Just as important, he was struggling financially and emotionally and was vulnerable to recruitment.

The previous months had been trying for Bell. His debt was mounting. His childhood sweetheart and wife of nearly three decades had divorced him, saddling him with a regular alimony payment. He had worked long assignments in Europe, further increasing his expenses. Compounding his misery was the loss of his youngest son in a fatal accident.

After remarrying, Bell moved to an apartment complex in the beachside community of Playa del Rey. One of his new neighbors was Zacharski. The two shared an interest in machine technology and a love for recreational tennis. They soon began spending time together both on and off the court. Bell would later tell a Senate committee that Zacharski eventually became his best friend. Or so it seemed.

Financially, Bell’s troubles lingered, and he declared bankruptcy. To make matters worse, his community was being converted into condominiums, and he would have to move. Zacharski offered to help. He asked Bell to help him make connections for his company at Hughes. Perhaps, Zacharski proposed, Bell could share some of his knowledge on various engineering matters as a paid technical consultant. Bell agreed, and the money began to flow. But ultimately Zacharski wanted more: classified information.

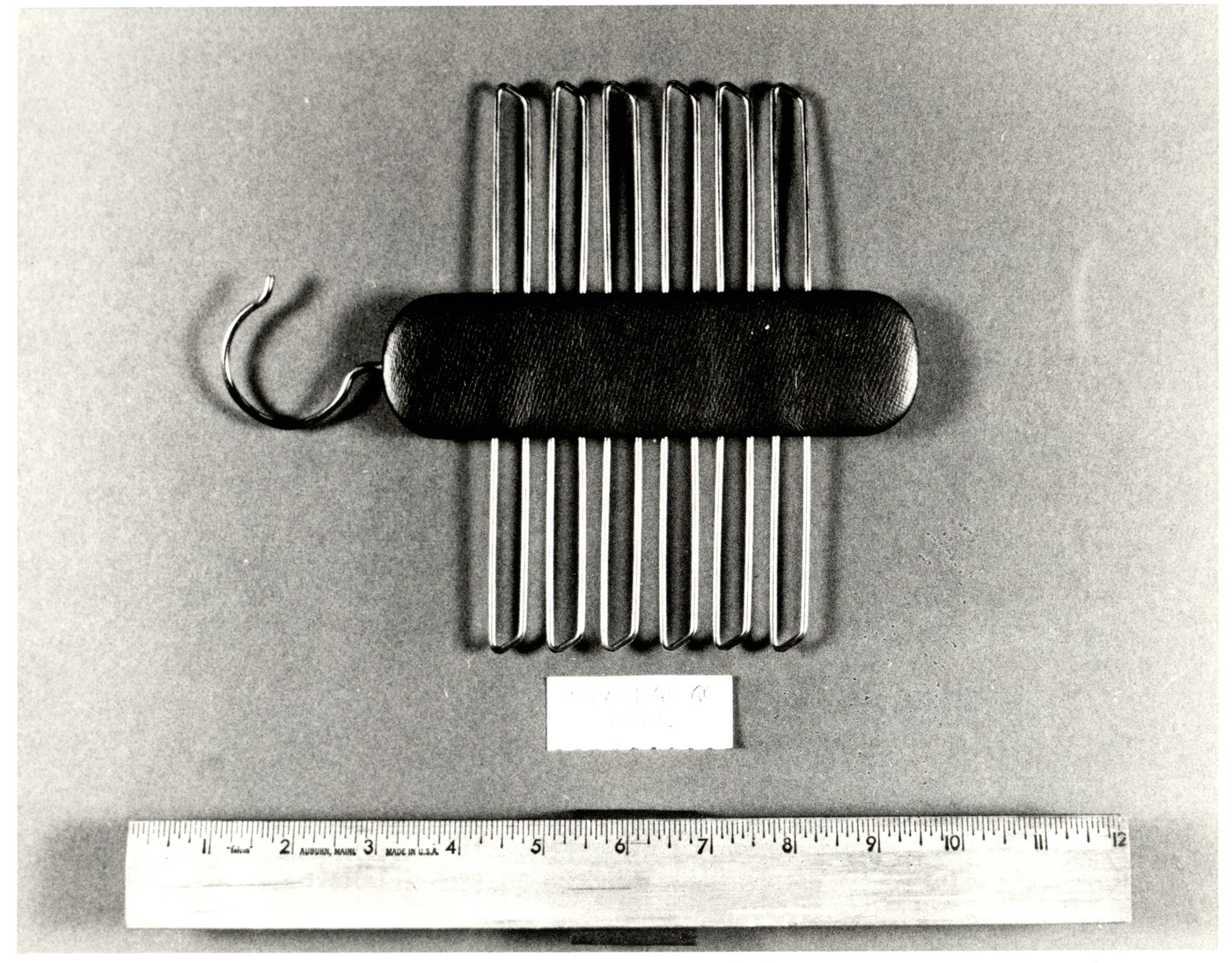

Bell began to show Zacharski projects he had worked on, like sophisticated radar systems and fixed weapons platforms. Zacharski supplied a camera and special high-resolution film so Bell could make photographs of confidential and secret plans and schematics. He would later receive other concealment devices like a tie rack and a large wooden chess piece.

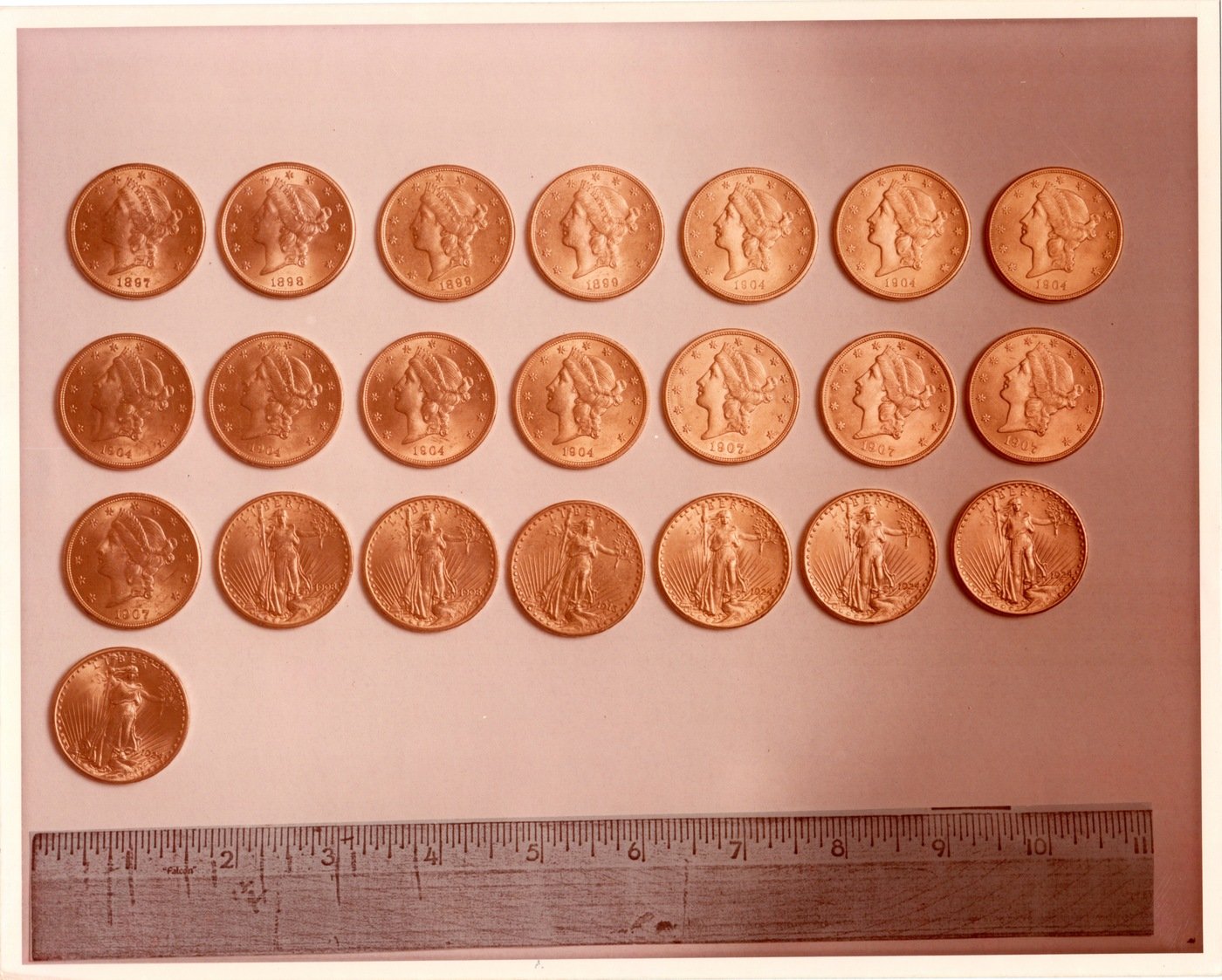

As Zacharski paid him a steady stream of cash and gold coins—ultimately totaling over $110,000 and possibly much more—Bell knew he had crossed a line from neighborly friendship to American turncoat. But Zacharski was skillful, keeping Bell in line with clever manipulation and possibly even threats to his family. The demands for information just continued to grow, including a series of trips overseas to deliver it.

Meanwhile, the FBI had become aware of Zacharski’s activities and had identified Bell as one of his sources. Agents began following both men, but not before Bell compromised another American radar system.

Coordinating counterespionage work here and overseas while building a case that can hold up in U.S. court is difficult, but the Bureau methodically gathered information and evidence. On June 24, 1981, agents from FBI Los Angeles confronted Bell. He soon confessed and allowed the FBI to use microphone surveillance at his next meeting with Zacharski. Four days later, both men were arrested and charged with espionage-related crimes.

Bell agreed to plead guilty and cooperate in the prosecution of Zacharski. By the end of the year, Zacharski was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Bell was sentenced to eight years. In 1985, Zacharski and three other Soviet bloc agents were exchanged for 25 people held in Iron Curtain jails for dissenting against Eastern European communist regimes.

Bell’s betrayal of his country mirrors the story of many others ensnared by foreign spies both past and present. Over time, vulnerable Americans are drawn in with money, companionship, attention, and other “carrots” in exchange for information, which gradually increases in importance, classification level, and quantity.

The threat remains. Espionage agents are as skilled, dangerous, and active as ever. To learn more about the risks, watch the FBI’s Game of Pawns video that tells the story of a regretful modern-day American who was led down the path to espionage and landed in jail.