The Pizza Connection

Painstaking Work Leads to Landmark 1980s Heroin Bust

Thirty-five years ago, in early April 1984, the FBI closed in on a real-life Mafia godfather.

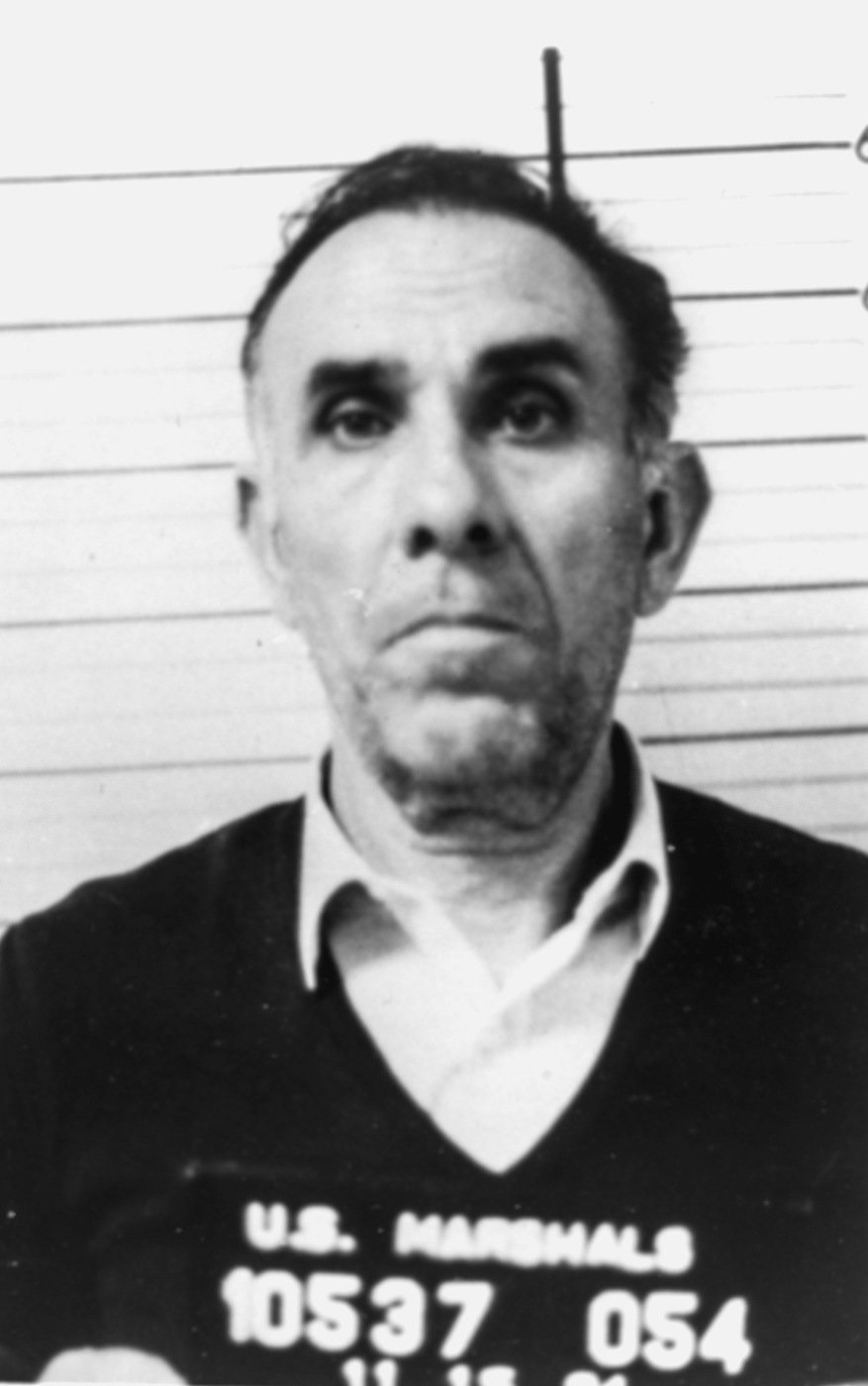

His name was Gaetano Badalamenti, and he was the former top boss of the Sicilian Mafia. Though banished from Sicily by rival mobsters in 1978, Badalamenti had continued to secretly lead one of the world’s most prolific drug cartels. Frequently on the move, he ultimately traveled with his wife and oldest son to Madrid. Pietro Alfano, a nephew who was his top operative in the American Midwest, took a flight from Chicago to meet them.

Little did Badalamenti know that Spanish authorities, acting on information from the FBI, were watching closely. On April 8, Badalamenti and Alfano ventured out onto the streets of Madrid and were quickly taken into custody. His son was arrested soon after.

The next day, the FBI conducted a carefully coordinated roundup of nearly 30 Mafia members and associates who worked with Badalamenti in the United States. Under the leadership of FBI New York, agents in six Bureau offices made arrests and carried out search warrants, seizing drug paraphernalia, large amounts of cash and weapons, and a trove of documents.

Among those swept up in the dragnet was Salvatore “Toto” Catalano, the owner of a bakery in Queens and a major figure in the Bonanno Mafia family based in New York. Catalano served as Badalamenti’s primary nexus to the American Mafia and the leader of his U.S. crew, a group of Sicilian immigrants known as the “Zips.”

The trial began on October 24, 1985, with 22 total defendants, all Sicilian-born men. As the government made its case over 16 grueling months—giving rise to the longest criminal jury trial in U.S. history to this day—two men pleaded guilty to lesser charges. One was brutally murdered, likely a victim of friction between Catalano and Badalamenti (Alfano was later shot and nearly killed in retaliation). That left 19 defendants by the time the jury delivered its verdict on March 2, 1987.

Federal prosecutors—including Louis Freeh, who would later become Director of the FBI—argued that the men were part of a vast, long-running drug conspiracy that touched four continents. The scheme involved purchasing morphine base from suppliers in Turkey, processing it into heroin in Sicily, smuggling it into the U.S., and then selling it through pizza shops and other Mafia-run businesses stretching from New York to Illinois and Wisconsin. Cocaine was also being imported from South America as part of the operation.

It was a lucrative business. From January 1975 until April 1984, an estimated $1.6 billion worth of heroin was shipped to this country in the plot. The cash profits were then illegally laundered through a web of banks and brokerages in the U.S. and overseas.

The case, dubbed “The Pizza Connection” by the news media because of the frequent use of pizza parlors as fronts for drug sales, was enormously complex and laborious. Undercover FBI agent Joe Pistone, who had infiltrated the Bonanno crime family in 1976, delivered crucial intelligence that helped set the case in motion. Over time, the investigation snowballed into a massive multi-agency and multi-national effort, with key contributions coming from the New York Police Department, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), U.S. Customs, and international authorities (including FBI international legal attaché offices) in Italy, Sicily, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, Brazil, Canada, Great Britain, Germany, and Mexico.

Over more than four years, the FBI and its partners gathered a mountain of records and evidence and utilized an array of investigative capabilities. They conducted surveillance on multiple players on multiple continents, sometimes around the clock. They traced and analyzed thousands of telephone calls, often from remote pay phones. Since the conspirators mostly spoke Sicilian and used coded phrases to conceal their true activities, turning their many covert conversations into plain English was especially challenging, requiring a team of expert translators from the FBI and elsewhere.

In the end, the painstaking efforts paid off. All but one of the final 19 defendants were convicted, with Gaetano Badalamenti and Catalano receiving hefty prison sentences.

The case has had some lasting downstream benefits as well. By fortifying partnerships, it helped pave the way for the expansion of the FBI’s network of legal attaché offices, so vital today in addressing global threats like terrorism and cybercrime. The first major drug bust after the Bureau was given concurrent jurisdiction with the DEA over narcotics violations in 1982, the probe also set an investigative standard for similar cases by employing the same suite of tools and approaches used by the FBI to address organized crime—most notably, the use of Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, to take down larger illicit groups and not just isolated actors.

Director Freeh would later put the case’s importance in perspective, calling it “the FBI’s first major, transnational criminal enterprise investigation and prosecution” and “a historic turning point for international police cooperation and coordinated enforcement action.”

The Pizza Connection was clearly a watershed, and 35 years later, it continues to pay dividends for policing and public safety.