Serial Killers

Part 4: White Supremacist Joseph Franklin

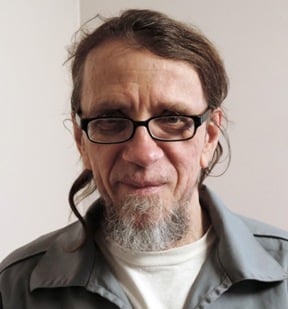

Joseph Paul Franklin. Image courtesy of Missouri Department of Corrections.

It was a deadly mix: a mentally troubled man from an abusive, broken home turned radical racist and then serial killer.

His name was Joseph Paul Franklin, and he went on a horrific killing spree beginning in 1977 at the age of 27. Before his reign of murder ended in 1980, he took the lives of at least 15 men, women, and children in some 11 states. He also admitted shooting civil rights leader Vernon Jordan and paralyzing pornography publisher Larry Flynt.

Franklin—born James Clayton Vaughn, Jr. before changing his name to reflect his admiration for Benjamin Franklin and Nazi Joseph Goebbels—was drawn to white supremacist ideologies as a teen. Dropping out of high school following a severe eye injury, he got married, became an abusive husband, and began racking up minor legal violations.

As his association with white supremacist groups grew, Franklin became increasingly confrontational toward minorities. By the mid-1970s, he had rejected even the most radical hate groups because he didn’t think they took their hatred far enough. He wanted to attack, not just sit around complaining. His self-directed “mission,” he later suggested, was to incite his fellow supremacists to action.

The summer of 1976 marked a turning point. On Labor Day weekend in Atlanta, Franklin followed an interracial couple and sprayed them with mace. This was his first known physical attack…it escalated from there. On July 29, 1977, he bombed a Tennessee synagogue; a few days later in Wisconsin, he killed two men—one black and one white—after encountering them in a parking lot.

For the next three years, Franklin drifted across the country, robbing banks (with some proficiency, according to law enforcement investigators) and using a sniper rifle to target his victims. He killed possibly more than 20 people and seriously injured six more.

By 1980, the FBI and its partners were closing in on Franklin. The often vast miles and lack of evidentiary connections between his crimes—as well as his skill at living the life of an anonymous drifter—kept Franklin under the radar for a time. This changed in September 1980, when an observant police officer in Kentucky noticed a gun in the back of a car Franklin was driving. A records check showed an outstanding warrant, and Franklin was brought in for questioning. He escaped while being detained, but the Bureau was on his trail.

Evidence from the car suggested multiple connections to the racially motivated sniper attacks across the country. The Bureau’s behavioral analysts contributed their insights, and the FBI shared its growing knowledge of Franklin’s characteristics and tactics with law enforcement and the public. Two details were crucial—Franklin’s racist tattoos and his reliance on blood bank donations for cash while between bank robberies.

Within weeks, a blood-bank operator in Florida contacted the Bureau about a man matching Franklin’s description. FBI agents immediately tracked him to Lakeland, Florida and arrested him on October 28, 1980.

Franklin faced legal action across the U.S. for the next two decades, eventually being convicted of multiple murders, attacks, and other crimes at both the state and federal levels. He was sentenced to life in prison and received the death penalty in several states. On November 11, 2013, he was executed in Missouri for the 1977 murder of a man standing in front of a synagogue in St. Louis.