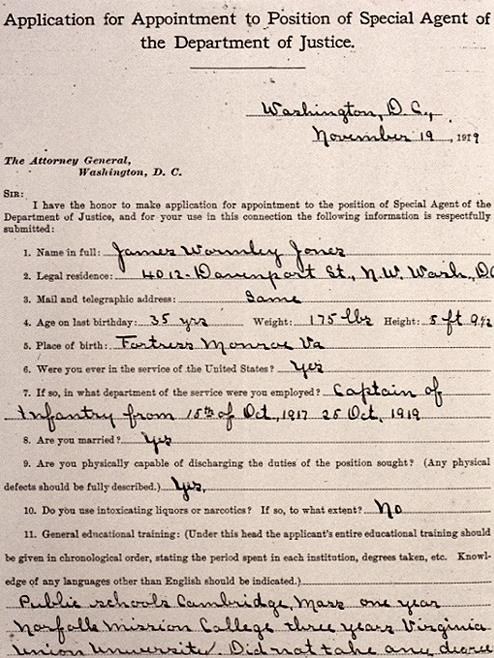

One hundred years ago, an African-American named James Wormley Jones applied to be a special agent of the Bureau of Investigation, the forerunner of the FBI.

Jones was eminently qualified. Born on September 22, 1884 at a military base in Hampton, Virginia, he had distinguished himself on the field of battle as an Army captain during World War I and as a police officer on the streets of Washington, D.C. His education included taking high school-level classes at Norfolk Mission College and college classes at Virginia Union University in Richmond. He later married and began raising two children with his wife Ethel. He was also an expert in explosives, having taught soldiers in Europe the proper handling and inner workings of bombs and grenades.

His application was approved, and with little fanfare, Jones began work.

Looking back, it was a historic appointment. The Bureau’s early personnel records are incomplete, but Jones is believed to have been the first African-American special agent—hired just 11 years after the creation of the organization that ultimately evolved into the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Other Stories in This Series

During Black History Month and throughout 2019, the FBI is proud to honor Special Agent Jones and the many African-American pioneers and professionals who have followed in his wake over the past 100 years, serving this organization and our country with distinction. The road has been far from easy for the FBI’s minority agents, but their countless contributions over the last century have played an invaluable role in making the Bureau stronger and the nation safer.

With his record of service, sacrifice, and courage, Agent Jones was a fitting trailblazer. He had joined the D.C. Metropolitan police force in January 1905 as a private first class. His older brother, Paul, joined the department in 1907. By 1910, James Jones was a private third class, eventually becoming a motorcycle officer.

In 1917, both brothers left the force to serve in the U.S. Army during World War I. James Jones was trained as an officer and assigned as the captain of Company F of the 368th Infantry, 92nd Division; his brother served under him as a lieutenant. One of the segregated African-American forces in the Army, their company was sent to Europe and fought bravely in the trenches at Argonne and Metz in France, near the Belgium and German borders.

In the book The American Negro in the World War by Emmett J. Scott, Captain Jones is said to have led his troops through heavy fog one night in 1918 and forcibly taken “over a mile of land and trenches which for four years had been held by the Germans” in an extremely dangerous and daring raid.

After the war ended, the brothers returned to D.C. and resumed their careers with the Metropolitan Police in early 1919. Paul Jones remained with the force for 17 more years, becoming a successful detective known for his skill in catching bunco artists, or con men. Tragically, he died in the line of duty in 1936. James Jones continued to rise through the ranks and was promoted to detective by 1919.

As an FBI special agent, Jones was assigned to the General Intelligence Division, created in response to terrorist bombings; his experience fit well with the mission.

Like other early African-American agents, Jones was tasked with handling the sensitive, difficult, and often perilous job of working undercover. Among his prominent cases serving in this capacity were the investigation of black nationalist Marcus Garvey, who was convicted of mail fraud in 1923, and the probe of the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), a Harlem-based radical group that promoted a separate black state. The ABB faded quickly as an organization, with its remaining elements folding into the Communist Party.

Jones went on to conduct a variety of investigations that were among the most common FBI cases of the day, including automobile theft and interstate prostitution.

Jones left the Bureau in April 1923, joining the Pittsburgh Police Department as a detective. He died in December 1958 at the age of 74.

As the Bureau marks a century of service by African-American special agents, its commitment to fostering diversity remains a top priority. As Director Christopher Wray noted recently, a diverse FBI is critical to its effectiveness and credibility and is “vital to getting the job done for our country.” The Bureau looks forward to celebrating the vital work of African-American agents over the coming year.