Assisting Crime Victims

A Navajo FBI employee serves victims after crimes occur on indigenous lands

After shoveling her SUV from a late-winter snow, Blanda Preston buckled in with her coffee and set off from her office in Flagstaff to Tuba City, Arizona, about 80 miles north on the Navajo Nation. The FBI victim specialist had a meeting there with a local victim advocacy group, so she was looking at about 90 minutes of what she calls "windshield time."

"One-way, it can take me one to four hours,” Preston said matter-of-factly, describing her more remote meetings and call-outs. “By the time I’ve met with one or two of my contacts, it’s sometimes just enough time to head back. So travel’s a challenge."

Navigating to distant, obscure, and sometimes missing pins on a map is part of the job in what the federal government refers to as Indian Country, where the FBI investigates the most serious crimes on nearly 200 reservations. More than 150 special agents work alongside tribal and federal partners on Native American lands. Federal law requires that victims of crimes like murder, child and adult sexual abuse, kidnapping, and violent felony assaults receive resources and support. For the FBI, that role belongs to the Victim Services Division (VSD) and victim specialists like Preston.

The familiar drive up Highway 89 took Preston in the direction of Preston Mesa, a modest landform in the desert named for her Navajo ancestors. She passed the site of her old jewelry stand, where, as a child, she sold beaded necklaces to tourists. And she slowed past the roadside memorial to her 14-year-old nephew, who was hit by a car and killed after some older kids furnished him with liquor and left him in the middle of the road at 2 a.m.

Digging out from a late winter snow at the Phoenix Division's Flagstaff Resident Agency is part of the job. A boundary marker on Highway 89 marks the southern edge of the Navajo Nation in Arizona. The Phoenix Field Office and its resident agencies have federal jurisdiction over 22 Native American reservations.

Preston’s intimate connection to the region and the Navajo Nation is part of what has made the 60-year-old former social worker such an asset to the Phoenix Field Office. It was also advantageous to the Albuquerque Division's Gallup satellite office, where she worked for 18 years before getting to Phoenix. She is one of seven victim specialists covering the state of Arizona and more than 20 reservations spanning thousands of square miles.

"It’s not difficult for me," said Preston, was born on the Navajo Nation and views the vast expanse as home. Her grandmother watched over the family when her parents worked summer jobs in Utah. She’s the fourth of 10 children, and has seen up close how Native American families struggle with alcohol, domestic violence, and isolation—in large part the result of historical racism and trauma. She graduated from Northern Arizona University with a degree in sociology/social work and a plan to help her community.

Preston was a young mother working as a social worker for the Navajo Nation Department of Social Services in Tuba City when she was attacked by a stalker in her home.

She remembers it clear as day: Almost everyone in her neighborhood was at a basketball game. Kids were playing outside. She was home with her 5-year-old daughter, who was holding an ice cream cone as they waited for a propane delivery.

She answered a knock at the door.

The man pushed his way in, grabbed her hair, and tried to pull her inside. With all her strength, she held the doorknob and screamed as he pulled. The man relented and then grabbed Preston’s purse and fled. She kicked him on the way out and then went to hold her daughter, who sat frozen on the couch as ice cream melted down her arm.

The police tracked the man down. But the cold legal process she endured at the time informs everything she does today.

"That experience is why I’m here," Preston said. "There was no victim services for me.

"I knew I had to do everything on my own. I had to appear in court. I had to write a letter to the judge. This was all something I had to do on my own. And that’s why I’m doing this—to ensure victim services are provided."

“She is trusted by the community she serves—she is a healer of her community.”

Jennifer Runge, executive director, Victim Witness Services for Northern Arizona

Blanda Preston speaks on her phone outside Victim Witness Services for Northern Arizona's Tuba City, Arizona, office.

For nearly 30 years, the FBI has worked on Safe Trails Task Forces alongside tribal law enforcement and federal partners—like the Bureau of Indian Affairs—on reservations across the country. But the U.S. government’s spotty history with Native Americans has left many on reservations justifiably guarded. And locals are often skeptical of law enforcement, in part because of entrenched violent crime and the lack of resources available to fight it. So building rapport and trust with crime victims is challenging. And it often falls to FBI victim specialists because investigators need to focus primarily on solving the crimes.

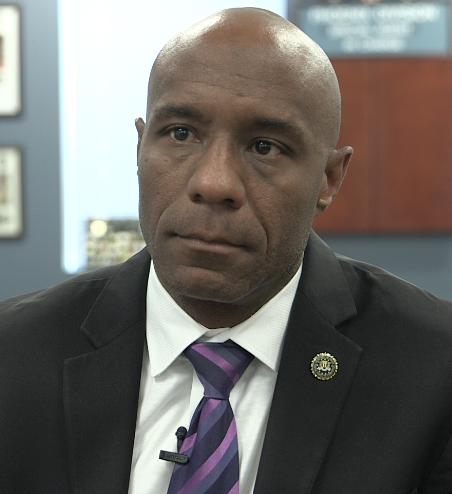

"They’re integral with everything we do because our focus is really on trying to catch the alleged offender and put them in jail," said Special Agent Jerry Grambow, who leads an Indian Country program and a squad covering some of the 22 reservations under the Phoenix Division’s jurisdiction. He said victim specialists are present throughout investigations, helping victims with necessities like getting to appointments and navigating the myriad resources available to them.

Shepherding victims through what might be the most difficult and confusing period in their lives isn't just the right thing to do, Grambow said. It also makes for more successful cases and criminal prosecutions.

"We need to make sure that our victim is well taken care of because good victims make good witnesses," Grambow said. "If we get to court or it goes to trial, it’s important that the victims have someone that they can lean on and have a rapport with prior to any of those situations."

Jerry Grambow, special agent, FBI Phoenix

Phylishia Todacheenie, a criminal investigator on the Navajo Nation in Tuba City, said victim specialists like Preston fill gaps in the patchwork of local services and service providers that are trying to help crime victims navigate the process. A victim of child sexual assault, for example, may have to travel for hours across rural tribal lands to reach a child advocacy center in Flagstaff or to meet with one of the FBI’s child and adolescent forensic interviewers (CAFIs)—a small, specially trained cadre of interviewers skilled at gathering evidence without further traumatizing children and others with mental or emotional disabilities.

"We live in a community where not everybody has money or transportation to get to these services," Todacheenie said. “By them helping us either transport the family or help pay for gas to get there, that really does help us a lot.”

Preston’s jurisdiction includes the western region of the Navajo Nation, as well as the Kaibab Paiute, San Juan Paiute, Hopi, Yavapai-Apache, and Yavapai-Prescott tribes. Over the years, her efforts in those communities showed a need for local victim advocacy resources, with staff who live in or near the communities they serve. Local advocates can get to victims’ homes faster than Preston can. And they sometimes meet her halfway to team up and escort victims and their families on long journeys.

"One of the areas we really collaborate on is connecting with Blanda and making up response time," said Laurelle Sheppard, program director of the Tuba City office of Victim Witness Services for Northern Arizona. "I think the victims really benefit from having a lot of different people on deck to support them."

“We need to make sure that our victim is well taken care of because good victims make good witnesses, which makes for good cases.”

Jerry Grambow, special agent, Phoenix FBI

More than a quarter of the FBI’s nearly 200 victim specialists and half of its CAFIs are assigned to jurisdictions that include Native American communities. In 2019, homicide was the fifth leading cause of death for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) males—and the seventh leading cause of death for AI/AN females, according to a 2021 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The analysis was part of a larger and ongoing federal effort to understand the dynamics behind what appears to be a growing number of missing or murdered indigenous persons.

The same CDC report paints a bleak picture of high levels of physical and sexual violence, and higher rates of adverse childhood experiences. These challenges are caused and compounded by a mix of historical, intergenerational, and ongoing traumas.

"Layers of trauma," said Sheppard, who is Navajo and was born in Tuba City. "Those things should be considered when you’re out there visiting families."

For Preston and Sheppard, it’s no mystery why children sometimes sequester in back rooms when federal officials show up on their doorsteps. In the 19th century, the federal government forced many Native American children into far-off boarding schools for assimilation. More recently, the growing awareness of child sexual abuse—in some cases spanning generations—has resulted in children being removed from homes for their own protection. It’s against this backdrop of deep-seated trauma and mistrust that Preston works every day, earning the confidence of victims and their families.

"I know the culture," Preston said. "I know the language. And it helps them to trust me—to trust that if we recommend some kind of forensic services for the victim, they’ll follow through with it."

Laurelle Sheppard, program director, Tuba City office of Victim Witness Services for Northern Arizona

Fiona Tuttle, a CAFI who works out of the Sacramento Field Office, works frequently with Preston. The FBI’s CAFIs provide regional coverage. So, when she's needed, Tuttle flies to Phoenix. She then meets Preston in Flagstaff or drives out to the victim's tribal community. She said Preston’s rapport with victims and families sets a firm foundation for her interviews.

"She has the face and the language of the people she serves," Tuttle said. "She really is kind of that bridge connecting me to the parents to trust me to tell their story. If we can build the trust with the parent or the caregiver, that goes such a long way for a child who has to disclose a very terrifying, heinous event, and know that their family, through Blanda, trusts me."

Albert Nez, a criminal investigator for the Navajo Nation, said the trust has been built over many years and at many crime scenes. "She always answers her phone," Nez said—a remark that carries a lot of weight from someone with more work than there are hours in the day.

Regina Thompson, assistant director of the Bureau's Victim Services Division, said the mission's success relies on relationships like these.

"At the heart of our victim services mission is understanding people and the context in which they live, which is why we have victim specialists stationed across the country, living and working in the communities they serve," Thompson said.

Preston’s phone rang while she was in Tuba City. It was her father, speaking in Navajo, calling to say a friend noticed his daughter was in town. It was a revealing moment of small-town word-of-mouth. And it crystallized how valuable it is for the FBI to reflect the communities it serves.

“She has the face and the language of the people she serves. She really is kind of that bridge connecting me to the parents to trust me to tell their story.”

Fiona Tuttle, child and adolescent forensic interviewer, FBI Sacramento

Blanda Preston and her father pose for a picture near Tuba City, Arizona.

"Definitely being part of that culture and that community brings a lot of credibility to our agency as outsiders," said Oscar Ramirez, a special agent in the Phoenix Division who has worked in Indian Country for more than 22 years. Ramirez recruited Preston to the FBI 18 years ago after seeing her work on the reservation. "What makes her unique is just who she is," Ramirez said.

Special Agent Grambow agreed that victim specialists who've established their bonafides make agents’ jobs easier. "I’m an outsider," he said. "They don't know me. But if they know that victim specialist who’s part of that community, that really does help make our cases."

FBI Phoenix Special Agent in Charge Akil Davis said his office is working on strengthening partnerships with state, local, and tribal partners. This spring, the office co-sponsored several events on tribal lands aimed at generating leads in scores of missing persons cases. Still more are planned with the Gila River Indian Community, the Tohono O’odham Nation, the Pascua Yaqui, and the Navajo Nation.

Meanwhile, the larger FBI is an active member of the Department of Justice Steering Committee to Address Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP), which works with tribal leaders and stakeholders to develop guidelines and practices to improve the law enforcement response on Native American lands.

And the Victim Services Division at FBI Headquarters recently launched an effort to hire more victim specialists for multiple locations with Native American reservations, including the Flagstaff office where Preston is based.

"We’re really trying to lean into these communities to let them know we’re here for them," Davis said.

Akil Davis, special agent in charge, Phoenix Division

After her meetings in Tuba City, Preston reflected on a career that has always been about helping her tribe—first, as a social worker for the Navajo Nation Department of Social Services and Ramah Navajo Social Services, and then, as an FBI victim specialist in the Bureau’s Gallup and Flagstaff offices.

"Coming back and giving back—it was one thing I wanted to do and worked for," Preston said.

Preston has three children and two grandchildren and still meets her dad for lunch when she's in town. He said a prayer in Navajo for her safety before tucking into his ice cream. Next to family, Preston said, work is fulfilling because it’s about doing something "valuable." And she's beginning to see the fruits of that labor on the Navajo Nation. She pointed to the proliferation of advocacy organizations stepping up to help crime victims in her own community.

"Blanda and Laurelle are advocates at heart, and they love their culture, their homelands, and their community," said Jennifer Runge, executive director of the Flagstaff-based Victim Witness Services for Northern Arizona, which opened the Tuba City branch. Runge said Preston always answers her calls, even on Christmas Day. "Her compassion is obvious, and her willingness to provide action on behalf of her client is evident immediately. She is trusted by the community she serves—she is a healer of her community."

Late in the afternoon, Preston steered her truck back toward Flagstaff.

"We’re getting there," she said, still nursing the coffee she began her day with. "My goal is to have victim advocates out in the community. I want to make sure that when I leave the Bureau, they can take on these responsibilities providing services to children and adult victims of crime. We’re getting there, and I’m really proud of that."

“At the heart of our victim services mission is understanding people and the context in which they live, which is why we have victim specialists stationed across the country, living and working in the communities they serve.”

Regina Thompson, assistant director, FBI Victim Services Division