Getting the Word Out

Navajo-language posters aim to reach critical audience

A radio broadcaster at a Navajo station in Farmington, New Mexico, reads from FBI posters seeking information about missing and murdered indigenous persons in New Mexico and Arizona. The FBI translated the posters into Navajo to better serve communities where a significant segment of the community speaks only Navajo. Download | Transcript

The FBI investigation into the violent murder of a 75-year-old Native American man seven years ago in New Mexico is picking up steam following novel efforts to generate new leads, including an initiative to translate the Bureau’s iconic Wanted posters into Navajo.

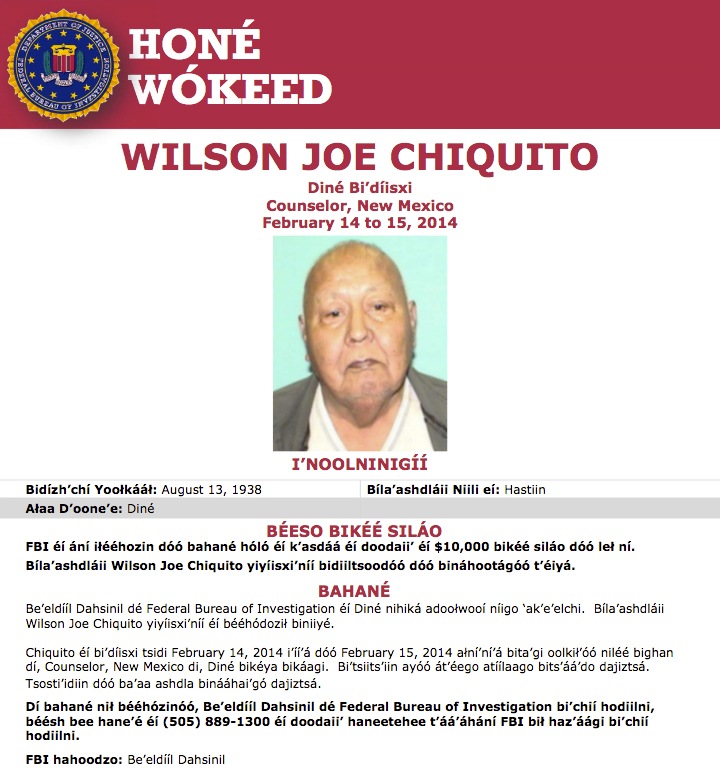

Wilson Joe Chiquito was killed in his home on the Navajo Nation Reservation in Counselor, New Mexico, in February 2014. He died from blunt force trauma to the head, but there were few leads to follow. Last year, in a renewed push to solve the case, the FBI office in Albuquerque released a new Seeking Information poster of Chiquito bearing his photograph, a $10,000 reward, and a full description of the crime—in Navajo. Since then, FBI offices in Albuquerque and Phoenix have released more than 15 posters in Navajo, with still more to come.

“It’s a huge benefit, and it really connects to our community,” said Phillip Francisco, chief of the Navajo Police Department, which has just under 200 officers policing 27,000 square miles and 180,000 people. “Our community really appreciates the outreach and embracing the culture and understanding that we have differences in the way we communicate. This will hopefully lead to resolutions that our people really so desperately want on some of these cases—especially the missing people cases where our families are going years without knowing what happened to their relatives.”

The work on the posters occurred in parallel with broader federal efforts to solve the alarmingly high number of missing-person and murder cases on tribal lands. In 2019, the Department of Justice launched the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons initiative to develop a more coordinated response, including better data collection, regional coordinators, and FBI rapid deployment teams that can reach remote locations relatively quickly. The initiative remains a top priority; the White House designated May 5 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day—a clear pronouncement that more needs to be done to support Native Americans in this effort.

Presidential Task Force

The FBI has investigative responsibilities over the most serious crimes in Indian Country—which includes nearly 200 federally recognized reservations across the U.S.—and we share the federal jurisdiction with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

In New Mexico, the Albuquerque FBI office has a long history of working with the Navajo Police Department. The Navajo Nation’s tribal lands cover large swaths of terrain in the upper reaches of New Mexico and Arizona and along the southern borders of Utah and Colorado. The rugged geography and spotty infrastructure—like lack of broadband technology—present challenges to communications. When FBI Albuquerque published Chiquito’s poster in Navajo last spring, the plan was to meet with tribal leaders to promote and coordinate an ongoing effort. But COVID-19 set in, closing borders and making it impossible to meet face-to-face, even a year later.

The initiative moved forward, however, and the FBI sought out ways to reach those who might have information to break a case. Agents plastered posters in post offices, grocery stores, and other heavily trafficked areas. Frank Fisher, the public affairs officer for FBI Albuquerque, collaborated with a radio station on the reservation to broadcast posters over the air in Navajo for listeners. The effort hasn't yet yielded any strong leads, but the gesture was appreciated and may yet yield fruit.

“Getting that word out to people in the community who only speak Navajo is a huge benefit and will hopefully get some tips to solving these cases.”

Phillip Francisco, chief, Navajo Police Department

Wilson Joe Chiquito

Wilson Joe Chiquito was killed in February 2014 at his residence in Counselor, New Mexico, when he was 75 years old. The cause of death was blunt force trauma to the head. A reward of up to $10,000 is available for information leading to the arrest and conviction of his killer. The FBI hopes that the Navajo translation of Chiquito's Seeking Information poster, seen here, will help generate leads in the case. More information

Additional Indian Country Cases

The FBI is seeking public assistance and information on multiple Indian Country cases, many of which involve missing or murdered individuals. Several of these cases have corresponding posters that have been translated into Navajo.

“I thought it was a very, very good idea to do that, because some of our elders and our older generation, they don't speak English. They only communicate in Navajo,” Francisco said. “So getting that word out to people in the community who only speak Navajo is a huge benefit and will hopefully get some tips to solving these cases.”

The push to translate FBI posters into Navajo originated at FBI Headquarters, where a small advisory committee pushed in recent years to include Navajo among the scores of languages the FBI qualifies and certifies its linguists to support. The American Indian and Alaska Native Advisory Committee (AIANAC) suggested using fluent Navajo-speakers already on staff to provide translations and interpretations to support work in the field. And in late 2019 and early 2020, two employees became the first to be recognized as qualified to provide Navajo language support across the FBI.

“Once that happened, it was a game-changer,” said Melinda Nakai, a native and fluent Navajo speaker who works as a community outreach specialist in the FBI’s Salt Lake City Field Office. “Now we can receive products from all over the FBI and translate them.”

Nakai’s job is to focus on the Native American communities in the Salt Lake City office’s jurisdiction, which reaches as far north as Montana. She grew up on a reservation in Arizona and has been with the Bureau for almost 30 years. She said when she learned about efforts to formally include Navajo in the FBI’s language translation offerings, she couldn’t say no.

“I feel like it’s a social responsibility,” said Nakai, whose father taught English and Navajo in their home when she was growing up. “I immediately thought, ‘I need to do this.’ And I went back to my early years when my father said, ‘You need to speak your language.’ And this was one of those times when I needed to do this.”

Public affairs personnel at FBI Headquarters immediately saw the value of translating materials into Navajo.

“I was thinking about the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons initiative and our investigative publicity posters and realized that we translate these into other languages, so why not Navajo now that we have official resources?” said Courtney Miller-Hileman, who is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina and served as chairperson of AIANAC. “We asked Frank (Fisher) if he was interested, and he ran with it.”

“Anybody who has responded to these homicides will tell you that these victims deserve justice.”

Frank Fisher, public affairs officer, FBI Albuquerque

Fisher was on the Evidence Response Team that assisted tribal police on the scene after Chiquito was killed. He said developing and innovating ways to connect can help communities like Chiquito’s cope and heal. And building up trust that the FBI is doing everything it can to solve a case can go a long way in an investigation that relies heavily on the public’s help.

“This was a well-loved member of the community who was beaten to death,” Fisher said. “Anybody who has responded to these homicides will tell you that these victims deserve justice,” Fisher said. “Their relatives deserve justice.”