Civil Forfeiture

Sale of Child Abusers’ Home Benefits Organization That Serves Victims

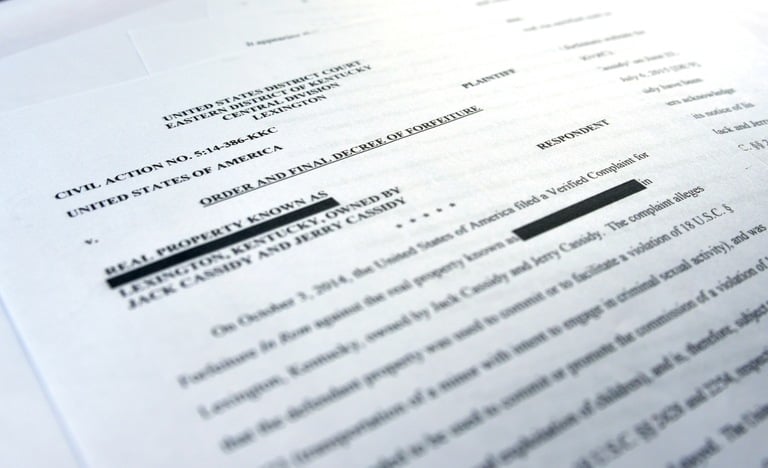

The home of Jack and Jerry Cassidy, who were convicted of sexually abusing children, was subject to civil forfeiture because their home was “used to commit or to facilitate” their crimes.

A Kentucky home where two brothers abused dozens of children over more than two decades has been sold following its civil forfeiture, and the proceeds will benefit a local advocacy group that serves young abuse victims.

The unique arrangement emerged following the investigation of twins Jack and Jerry Cassidy, of Lexington, who pleaded guilty in 2015 to state charges of child pornography and sexual abuse of minors. The brothers were longtime Boy Scout leaders and trusted members of the community, and many of their criminal acts were committed in the house where they held their meetings. Because the property played a central role in the crimes—including facilitating the movement of minors across state lines—local investigators and prosecutors worked with the U.S. Attorney’s Office to seize the property under federal asset forfeiture laws. The effort set in motion a novel approach to supporting a program for young victims like those the Cassidy brothers abused from 1963 to 1986.

“It’s a good example of what can be done for the good of the community,” said Wade Napier, an assistant U.S. attorney who helped implement the civil forfeiture.

The “good” in the case was how officials used a powerful federal law enforcement tool to punish criminals and benefit the community where so many—at least 30 victims—were affected.

Here’s how it worked: Proceeds from the auction of the Cassidy brothers’ house went to the FBI, which shared the funds with its partners in the case—the Lexington Police Department, which led the criminal investigation, and the Fayette Commonwealth Attorney’s office, which prosecuted the state criminal case. The sharing framework is outlined under the federal government’s asset forfeiture equitable sharing program, which says the FBI can transfer up to 80 percent of forfeiture proceeds to local law enforcement who assist in a case, and partners can then share up to $25,000 a year with community-based organizations that serve a law enforcement purpose. In this case, the beneficiary was the Lexington-based Children’s Advocacy Center of the Bluegrass, a non-profit serving abuse victims across 17 counties in Central Kentucky.

“The civil asset forfeiture was directly applicable to the terrible conduct we saw from the defendants in this case,” said Napier, who serves in the Eastern District of Kentucky.

The Cassidy brothers’ crimes were uncovered on August 11, 2014, when police responding to a 911 call by a concerned friend found Jack Cassidy at the front door of the rambler, refusing their entry, and his brother on the floor bound and motionless—apparently the result of a consensual game. When they finally got inside, police saw framed photographs of young, semi-naked boys in suggestive poses, many with taped-on labels of “sweet,” “pretty,” and “wow.” Police also discovered the brothers’ hand-written journals documenting their victims and the abuse that occurred in the house and on Scout trips.

“This is a great example of how we can work together as one for the community.”

Kimberly Kidd, special agent, FBI Louisville

Special Agent Kimberly Kidd, who investigated the case out of the FBI’s Louisville Field Office, said “there was no question” of whether the brothers’ home should be seized. “It’s not like the abuse happened just one time in this house,” she said. “For decades, they were molesting children in this home.”

As the investigation progressed, Lexington Police Department officers focused on the criminal case while Kidd traced the brothers’ travels to determine if federal crimes occurred. The brothers, who were in their 70s at the time of their arrest, ultimately pleaded guilty to nine state charges, assuring they would spend the rest of their lives in jail.

Meanwhile, the federal focus turned to seizing the home, since Kentucky state law doesn't have a pathway for real property seizures and forfeitures in child exploitation cases. For Kidd, who has had numerous cases that relied on the use of the Children’s Advocacy Center, it seemed like a natural fit to help fund the center with proceeds from the brothers’ assets.

“They are always available to support law enforcement, and I would love to see law enforcement give back,” Kidd recalled thinking. “This is a great example of how we can work together as one for the community. We’re in this together and we recognize that.”

The brothers were each sentenced to 20 years in jail; Jerry Cassidy died in September at age 79. Investigators documented more than 30 victims, but the case was cemented on the testimony of three individuals who told the court how they were exploited decades ago. Kidd described the case as unnerving because the Cassidy brothers were in positions of authority and trust in their own community. “They completely took advantage of that for three decades,” Kidd said.

The auction of the Cassidy brothers’ home netted proceeds of about $84,000, which was distributed through the equitable sharing program with the Lexington Police Department and commonwealth’s attorney’s office. Under the arrangement, the agencies are giving the money to the Children’s Advocacy Center, which has already put the funds to work in the form of a new roof, upgraded technologies and new recording equipment in the center’s forensic interview suites.

Winn Stephens, executive director of the center, said the funding and support from the FBI and the local agencies affirmed his organization’s role with law enforcement.

“They have the option of expending those funds themselves or passing them through to an organization like ours,” he said. “I think it really made us feel validated in the work that we do and the type of partners we are that they were so willing to share those funds with us.”

Proceeds from the sale of the Cassidy brothers' home is benefiting the Lexington-based Children’s Advocacy Center of the Bluegrass, a non-profit serving abuse victims across 17 counties in Central Kentucky.