International Law Enforcement Training

Celebrating 20 Years of Partnership and Excellence

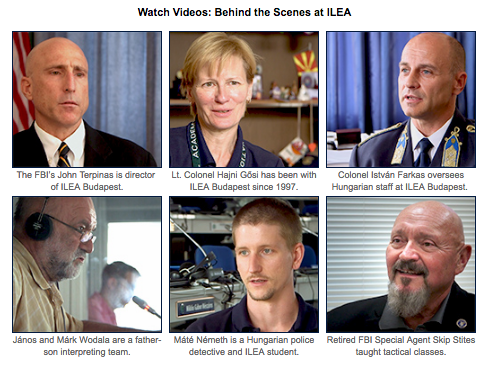

FBI Special Agent John Terpinas, director of the International Law Enforcement Training Academy (ILEA) in Budapest, Hungary, speaks at a July 17, 2015 event there celebrating the organization’s 20th anniversary and the graduation of its 100th core class.

American law enforcement celebrated a milestone today in Budapest, Hungary: the 20th anniversary of an international training program whose success continues to prove that despite diverse cultures, politics, and religions, police officers everywhere share many more similarities than differences.

The FBI was instrumental in establishing the International Law Enforcement Academy (ILEA) in Budapest in 1995, and since that time, instructors from a variety of U.S. federal agencies have provided expert training to more than 21,000 law enforcement officers from more than 85 countries. Just as importantly, the program encourages officers of different nationalities to build lasting professional relationships to better fight crimes that increasingly spill across borders. The concept has worked so well that other ILEAs—all funded and run by the U.S. Department of State—have been opened in Thailand, Botswana, El Salvador, and America.

View videos below.

View videos below.

“It’s one of the program’s biggest strengths,” said FBI Special Agent John Terpinas, director of ILEA Budapest. “Beyond the classroom instruction, we help to build relationships, and those relationships—that ILEA network—have opened a lot of doors over the last 20 years that might otherwise have been closed.”

“From the perspective of the U.S. government and particularly the FBI, I can’t emphasize enough how important ILEA is for the entire international law enforcement community,” noted Robert Anderson, Jr., executive assistant director of the FBI’s Criminal, Cyber, Response, and Services Branch. Anderson was on hand at events in Budapest to celebrate the anniversary, along with foreign dignitaries and U.S. Ambassador to Hungary Colleen Bell.

Also in attendance was former FBI Director Louis Freeh, who in 1994—only a few years after the fall of the Berlin Wall—led a U.S. delegation to meet with representatives from 11 nations in Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Europe. The mission was to determine if new joint programs with these emerging democracies could be created to fight the growing threat of transnational crime.

The former Soviet countries had little experience with Western methods of policing and operating a criminal justice system under the rule of law, and they asked Freeh for FBI training.

“Many newly appointed police chiefs were democratically minded but had little previous police experience and no experience in Western law enforcement leadership and methodology,” said Miles Burden, a retired FBI special agent and former ILEA director who was on the 1994 trip. “They had no experience in things as basic as serving a warrant. You couldn’t wave a magic wand and change that without extensive training.”

A little more than a year later, ILEA Budapest was offering instruction to its first class, and in the spring of 1996, Freeh was there for the first graduation ceremony. “The reasons for the academy’s success are apparent to anyone who looks in realistic ways at the world around us,” he said at the time. “Crime of all kinds has grown to alarming levels on an international scale. No country by itself, no matter how strong it may be, can face all of this crime alone and hope to succeed.”

While most of the Eastern European countries that participate in ILEA Budapest today are no longer emerging democracies, the need for joint training and partnerships is as important as ever.

“ILEA is more relevant now in the world that we live, particularly with law enforcement challenges, than when it was established 20 years ago,” Freeh said this week, adding that he was “extremely proud” of what the program has accomplished and the dividends it is paying. Early ILEA participants, for example, have now assumed leadership roles in their organizations.

“Some of our students have risen all the way to the ministerial level in their governments,” Terpinas explained. “We hope that their ILEA experience will help them influence their government’s policy and decision making toward good governance and shared values that promote democracy.”

ILEA Budapest owes much of its success to the Hungarian government that hosts the academy and the Hungarian staff who take care of the day-to-day operations—tending to students who speak different languages and may have never traveled across their own border or met an American law enforcement officer before.

“We are really lucky here in ILEA Budapest because we have an outstanding relationship with our Hungarian partners,” Terpinas said. “The staff here is spectacular. Some have been here since the day the door opened.”

Police Colonel István Farkas, who oversees the Hungarian staff at ILEA Budapest, explained that the Americans who serve as director and deputy director of the academy usually rotate every three years, while the Hungarian staff remains constant. “What makes this academy function at high quality is that its staff has been almost the same during the course of all these years,” Farkas said through an interpreter.

Farkas, who has been a senior leader at ILEA Budapest for 16 years, added that the U.S. government takes the international training program very seriously. “The American law enforcement professionals are not conducting a marketing activity here,” he said. “What they do is they transfer true knowledge.”

ILEA’s core course of instruction—based on the FBI’s National Academy program for U.S. law enforcement personnel—is a seven-week program with blocks of instruction in various disciplines. Each class consists of about 50 mid-career officers from three or four different countries.

FBI instructors teach blocks on public corruption, counterterrorism, and tactics, while the U.S. Secret Service teaches about counterfeiting, and the Drug Enforcement Agency teaches about drug trafficking. “Everybody comes and teaches their expertise,” Terpinas said. The instructors are among U.S. law enforcement’s most experienced members.

In addition to the classroom and tactical instruction, students are encouraged to exercise and are required to participate in a variety of team-building activities—which help them form bonds intended to last a lifetime.

ILEA Students Wearing Headsets for Translations

ILEA Students Wearing Headsets for Translations

Located in a Ministry of Interior facility consisting of historic buildings that have been refurbished with state of the art equipment, ILEA Budapest overcomes the language barrier for students through the use of seasoned interpreters.

“Our classrooms are like a mini United Nations,” Terpinas said. “The students are all wearing headsets, and we can translate up to four languages simultaneously. So the instruction is in English, the materials that the students are looking at on their laptops are in their language, and then they are receiving the instruction, simultaneously, in their language from our interpreters.”

János Wodala, a longtime ILEA interpreter, likened his role to a soccer referee. “If it’s a good game,” he said, “you don’t even notice that the referee is on the field. So if interpretation goes well, and if it goes smoothly, you don’t even notice that there’s an interpreter.”

Máté Németh, a Hungarian police detective who was part of the 100th core class that graduated today to coincide with the 20th anniversary, spent the past seven weeks with fellow Hungarian officers and classmates from Macedonia and Bulgaria. Prior to his ILEA experience, he had never encountered police officers from those countries.

“I never met Macedonians or Bulgarians,” he said, “not on the professional level. So it was a really good time to get to know some colleagues from the surrounding and neighboring countries.” He added, “The biggest point of the whole ILEA is networking—getting to know these people. Because the criminals don’t stop at our borders, so we shouldn’t stop there either.”

More information:

- FBI International Operations

- ILEA Budapest

- Department of State Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement

- Video: U.S. Embassy Budapest Documentary on ILEA Budapest

Watch Videos