Corruption in a Small Texas Town

Investigation Dismantles Family-Run Criminal Operation

Public corruption arrests and convictions in major metropolitan areas usually garner a great deal of national attention. But big cities don’t have a monopoly on crooked politicians—they can be found anywhere.

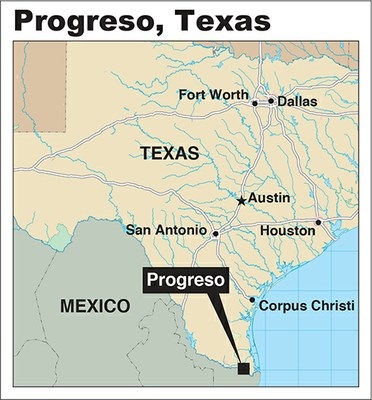

Like Progreso, Texas, a small town a few miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border. For almost a decade—from 2004 to 2013—several members of the same family, all Progreso government officials, used their positions to exact bribes and kickbacks from city and school district service providers. Through their illegal activities, they distorted the contract playing field, cheated the very citizens they purported to serve, stole education money from the children whose educations they were supposed to ensure, and lined their own pockets in the process.

Until the FBI got wind of what was going on, that is, and opened a case. Our investigation—which included confidential sources, undercover scenarios, financial record examinations, and witness interviews—collected plenty of evidence of wrongdoing and ultimately led to guilty pleas by the defendants. And on August 11, 2014, they were all sentenced to federal prison terms.

Until the FBI got wind of what was going on, that is, and opened a case. Our investigation—which included confidential sources, undercover scenarios, financial record examinations, and witness interviews—collected plenty of evidence of wrongdoing and ultimately led to guilty pleas by the defendants. And on August 11, 2014, they were all sentenced to federal prison terms.

Jose Vela, the patriarch of the Vela family and leader of the corruption scheme, served as maintenance and transportation director for the Progreso Independent School District (PISD), which from 2004 to 2013 received more than a million dollars per year in federal program grants and funds from the U.S. Department of Education. But Vela’s scope of influence was much broader than his job title suggested, thanks in part to the positions of his sons—Progreso Mayor Omar Vela and Michael Vela, president of the PISD Board of Trustees.

The elder Vela let it be known that contracts with the school district could be bought, and he accepted bribes and kickbacks from contractors willing to pay. Jose Vela maintained control over the PISD and its board of trustees through a system of reward and retaliation: He distributed bribe money he received from contractors to trustees who voted as he directed; when trustees didn’t vote with him, they were retaliated against—usually demoted, transferred, or ultimately forced out of their positions.

Vela’s influence was not just over the PISD. With his sons’ help, he took bribes and kickbacks from any entity—like construction companies and architectural firms—that wanted a public project contract with the city of Progreso. Vela, in effect, created a “pay to play” contracting environment in the city for such projects as municipal parks and libraries. He even extracted money from the lawyer who was supposed to be advising the school board.

Omar and Michael Vela assisted their father by collecting bribes from contractors and delivering the payments to him, keeping a portion for themselves.

A third Vela son was sentenced to a federal prison term as well for his role in a separate but related scheme. Orlando Vela, employed by the PISD as a risk manager, also headed a company purportedly in the business of supplying office products to school districts and admitted submitting thousands of dollars worth of phony invoices to the PISD for office supplies never received by the district.

And finally, also caught up in the overall corruption scheme was Jesus Bustos, who admitted to paying bribes and kickbacks to obtain contracts for his architectural firm. He was sentenced on August 27, 2014.

Public corruption at any level of government cannot be tolerated, and the FBI—uniquely situated to investigate it—will continue to address these allegations wherever we find them.