Snake Oil Salesman

Man Cheated Would-Be Investors in Oil Boom Housing

Convicted fraudster Ronald Johnson showed this photo to investors in his Bakken housing project to convince them that their money was being used as intended—but this construction site was not the property the investors had visited. This was an initial clue that the investment was a scam.

Like many who are looking for economic opportunity, Ronald Johnson saw the oil-booming Bakken region in North Dakota and Montana as a chance to make money.

Yet unlike oil workers putting in an honest day on the job, Johnson was a con artist who simply separated innocent investors from their money while enriching himself.

The Bakken Formation, a vast, oil-rich territory that runs from North Dakota to eastern Montana and north into Canada, has experienced an influx of workers in recent years who need housing while they work in the oil industry. When Johnson visited Watford City, North Dakota, he noticed oil workers were parking their RVs in indoor RV parks to get out of the cold and take advantage of shared services, like laundry. He decided to pitch investors on the idea of building indoor RV parks for Bakken workers.

His sales pitch offered investors “memberships” that would entitle them to a percentage of rental and other income generated by the parks based on how much they invested. Johnson also sold his scheme as a good deed to help oil workers who needed warm, indoor housing in the harsh North Dakota winters.

“Some of the victims were completely taken in by the concept of a financial investment with the opportunity to help people,” said Special Agent Christopher Lester of the FBI’s Minneapolis Division, who investigated this case along with Special Agent Julie Barrows of the Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigation. “He preyed on their values to get them excited about investing in something that had the potential for profit and also to help these workers in the Bakken.”

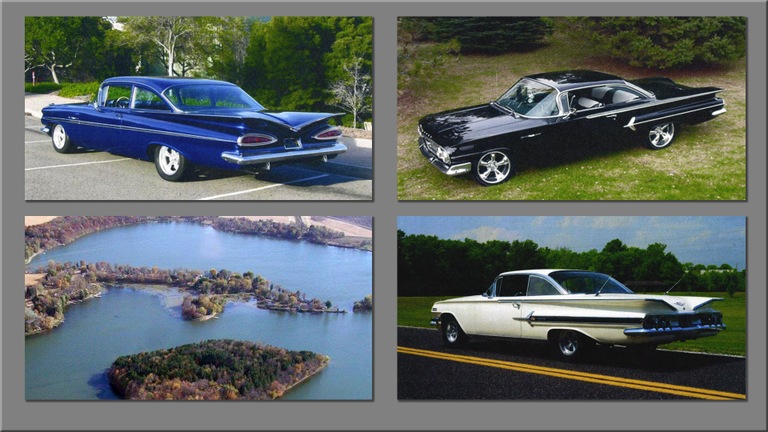

Johnson told his investors he would buy property in North Dakota and begin the building process. Instead, he stole their money and spent it on himself or repaid previous investors clamoring for their money back. He also funded his own cattle farm, bought land (including a Minnesota island), and purchased more than a dozen vintage cars.

Johnson’s investors soon started questioning him about the park and what he had done with their money. He went to great lengths to cover his tracks, including sending one investor a picture of a construction site that wasn’t actually of the property the investors had visited. Once they found each other and began comparing the stories Johnson had told them, Johnson’s scheme began to unravel. Through search warrants, interviews, and other investigative tactics, the FBI and IRS-CI discovered Johnson was not simply a bad businessman—his intent was to defraud his victims all along.

“His sales pitches were very targeted to what the person was looking for,” Lester said. “If they wanted a solid investment, he’d point to existing RV parks and their success. If another person was more interested in the philanthropic aspect, he would highlight how these poor workers were freezing outside, and it was God’s work to help them.”

“Johnson is a smooth talker, just a career con man who would basically say anything to separate a person from their money.”

Christopher Lester, special agent, FBI Minneapolis

These vintage cars and private island in Minnesota were just some of the ill-gotten gains obtained by Ronald Johnson as a result of his scheme.

Some of Johnson’s victims were close to him—such as his former girlfriend and his pastor—making them more susceptible to the pitch. Other victims were a couple in the RV business Johnson recruited by offering a business partnership, as well as a Minnesota businessman looking to help the Bakken workers. The victims lost anywhere between $200,000 and $800,000 each.

Thanks to the asset forfeiture process, some victims will recoup a fraction of their money through the sale of Johnson’s ill-gotten gains, but it will be a minimal amount compared to what they lost. Losing such a significant amount of money has had life-altering effects on the victims. At Johnson’s sentencing hearing, one victim said she will have to change her retirement plans and will struggle to take care of her aging mother.

“Johnson is a smooth talker, just a career con man who would basically say anything to separate a person from their money,” Lester said. “We understood it was important Johnson had his day in court. If he didn’t, he was just going to continue to defraud people.”

Johnson was convicted of wire fraud and money laundering in June. In November, Johnson was sentenced to more than 10 years in prison.

“Mr. Johnson took advantage of every opportunity—and dollar—provided to him,” said Acting Special Agent in Charge Hubbard Burgess of the IRS-CI St. Paul Field Office. “Investment decisions are difficult enough without individuals like Mr. Johnson trying to steal hard-earned dollars. Fortunately, the IRS-CI and FBI work side by side in a united front against financial crime and to help keep the public safe.”