Father-Son Plane Hijacking in 1961 Prompted Focus on Airplane Crimes

FBI investigated four hijacking cases in four months

A string of airline hijackings in 1961—including one by a father-son duo that was diffused by a persuasive FBI agent in El Paso—led to new federal penalties for crimes aboard aircraft during what many regard as the golden age of flying.

By the summer of 1961, there had already been three hijacking attempts—two successful—in the U.S. that year. Then on August 3, a paroled bank robber named Leon Bearden and his son Cody, 16, boarded Continental Airlines flight 54 in Phoenix along with 72 other passengers. They sat next to each other in coach as the plane took off for El Paso, Texas.

Not long after take-off, as many passengers dozed, the father and son signaled for a flight attendant to come to their seats. As she leaned in to quietly ask what they needed, Leon Bearden shoved a snub-nosed revolver into her ribs and demanded that she take him to the pilots.

Entering the cockpit, Bearden ordered the pilots to fly to Mexico, intending to force them to fly from there to Cuba. When he was informed there was not enough gas for the southern trip, he agreed to allow the plane to land in El Paso as planned. The plane landed just after 2 a.m.

The control tower alerted law enforcement as soon as they realized the flight had been hijacked. Members of the FBI, El Paso Police Department, El Paso Sheriff’s Office, the Texas Department of Safety, and others all raced to the airport. FBI El Paso Special Agent in Charge Francis Crosby took command of the joint operations post and began to evaluate the crisis.

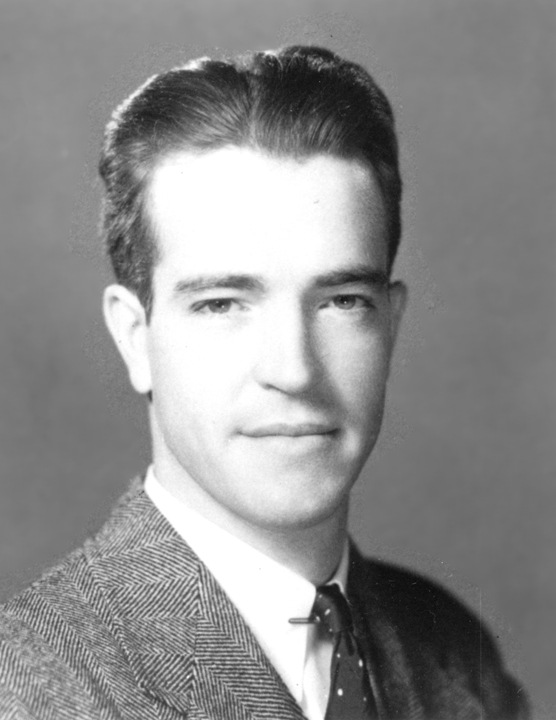

FBI El Paso Special Agent in Charge Francis Crosby investigated the Bearden hijacking in 1961.

Inside the plane, the crew stalled for time. As re-fueling continued, the Beardens demanded the passengers remain seated with the doors closed. After the hijackers agreed to allow a pregnant passenger to get off the plane, they were persuaded to allow most of the other passengers to exit as well. Six crew members and four passengers who had volunteered to stay on board remained. Among the volunteer hostages was a Border Patrol agent.

Standard hijacking procedure at the time was to watch and wait to avoid escalating the crisis and risking injury or aircraft damage. Unless, that is, the hijacker ordered the plane to take off.

By 6 a.m. that morning, refueling was dragging on, and the hijackers were becoming increasingly nervous. They demanded the plane leave. As the fuel trucks moved away, the plane’s engines fired up. Agents, however, were ready to execute a plan agreed to by FBI Headquarters and Continental executives. As the pilots slowly taxied toward the runway, Crosby ordered his agents to shoot out the tires.

The plane was soon surrounded by law enforcement and would go no farther on its flat tires. The temperature on the tarmac climbed from the 70s towards the 90s, and the airplane air grew stifling. The air conditioning was not working.

At this point, Bearden allowed Crosby to come on board and discuss matters. Crosby made it clear that the plane was not going to take off and that no replacement would arrive. The Beardens would be prosecuted criminally. In other words, the only mitigation was cooperation. Crosby told Bearden he should surrender. Bearden, in turn, said he and Cody didn’t want to harm anyone, but thought this was the only way they could get to Cuba.

As Crosby and Bearden talked, additional back-up infiltrated the cockpit of the plane. Shortly before noon, they made their presence known, and Crosby and the Border Patrol official immediately secured Leon Beardon and his son. The two were arrested and led off the plane.

They were immediately arraigned on several charges. Cody Bearden pleaded guilty under the Juvenile Delinquency Act and served prison time until he turned 21.

Leon Bearden was quickly convicted at trial and on October 31, 1961, was sentenced to life imprisonment for kidnapping and other crimes. The kidnapping charge was eventually vacated by the Fifth Circuit court on account of the possibility that pre-trial publicity tainted the jury, but Bearden’s conviction on obstruction of interstate commerce by extortion was upheld. He was sent to federal prison.

The Bearden case followed successful hijackings that year on May 1 and July 24 and an unsuccessful attempt on July 31.

After the Bearden case became the fourth hijacking in as many months, Congress amended the 1958 Federal Aviation Act to add a number of federal charges to address crimes committed aboard an aircraft. Bearden, of course, could not be charged under the new law, but it did increase the tools the government had at its disposal to go after these criminals.

Hijacking Was Nothing New to Pilot

Pilot Byron Rickards had been victimized in one of history’s first airplane hijackings attempts. In 1931, after landing a plane in Arequipa, Peru, revolutionaries tried to force him to fly them around to drop propaganda leaflets on the countryside. Rickards refused, and after a 10-day standoff, the revolutionaries released him.

Three decades later, he was going through his pre-flight checklist. On August 3, 1961, Continental Airlines flight 54 was scheduled to fly from Los Angeles to Houston with stops in Phoenix, El Paso, and San Antonio.

The first stage of the trip went off without a hitch. The plane arrived in Phoenix around dusk, and the crew welcomed 74 passengers on board, including a paroled bank robber named Leon Bearden and his 16-year-old son, Cody.