FBI Seattle History

Early 1900s

The first official FBI office in Seattle opened around 1914 under the leadership of Special Agent in Charge Fred Watt. The office played a role in the Bureau’s national security efforts during World War I, and in the 1920s it pursued automobile thieves, impersonators, and others who violated federal criminal law.

During these early years, the office was located in the Douglas Building at 4th Avenue near University Street. One employee from this period remembered that the Seattle FBI consisted of “the special agent in charge, eight or ten special agents, a chief clerk, and a stenographer. The division covered the state of Washington, and agents conducted their investigations on foot or by taking the street car or the bus. They were not issued guns at the time, but the office did have one handgun that was locked in a safe; however, there was no ammunition.”

1930s

In 1930, the office moved into the new Northern Life Tower (now known as the Seattle Tower) at 3rd Avenue and University Street. Two years later, the Seattle office was closed, and a new FBI office in Portland took over its territory.

Early Seattle Division

During this time, a major Bureau investigation unfolded in Washington state. On May 24, 1935, George Weyerhaeuser, the nine-year-old son of prominent lumberman J.P. Weyerhaeuser, of Tacoma, was kidnapped on his way home from school. After the family paid a sizable ransom, the boy was released on June 1. Bureau agents quickly identified the kidnappers and recovered much of the ransom money.

On March 11, 1937, Ray C. Suran was directed to proceed to Seattle and “assume the duties of Acting Special Agent in Charge of the Bureau Field Division to be opened there.” He reestablished the office in the Vance Building at 3rd Avenue and Union Street. It has been in continuous operation ever since.

The division soon had a major national case on its hands. On December 27, 1936, 10-year-old Charles Mattson was kidnapped from his Tacoma home. Two weeks later, his body was found by a hunter. The ensuing investigation—codenamed MATTNAP—was first opened by the Portland Division but soon fell to Seattle to continue. The search for a killer was lengthy and exhaustive—as late as 1945, the office still had eight agents assigned to the case. Unfortunately, the search was also unsuccessful, and the murderer was never found.

1940s and 1950s

With the onset of war in Europe, the Bureau began to expand its national security work. Since Seattle was a major port city and a center for U.S. wartime production, especially around Puget Sound, the division played a central role in this growing priority, even before the U.S. entered the conflict. In May 1939, FBI executive Ed Tamm suggested to Director J. Edgar Hoover that it was important to prevent sabotage at the Boeing Plant in Seattle, which was producing planes for the U.S. Army. Tamm also proposed that an agent should be exclusively assigned to investigate espionage, counter-espionage, and sabotage cases in Seattle and in several other key Bureau divisions.

This work expanded quickly. In January 1940, Seattle reported that it was handling five national security-related investigations, including two espionage cases. Of particular concern was the espionage activity being conducted by Japanese nationals ostensibly studying the English language on the West Coast. The key role of Manhattan Project researchers at the nuclear reactor in Hanford, Washington—part of America’s effort to develop an atomic bomb—was also a concern, leading to a significant increase in the number of agents assigned to the Seattle Division and its Richland Resident Agency. The work of these agents continued after the war as the arms race began to heat up. By 1945, the division was handling hundreds of national security cases, including ones related to the Boeing Company, the Navy Yard, the Hanford Nuclear Reactor, and the entire coast line, which was considered a target for possible attacks.

During World War II and into the early years of the Cold War, the FBI was conducting background checks on U.S. government employees involved in atomic energy, working in defense plants, and holding other sensitive positions, leading to additional work and leads for the Seattle Division. In 1946, Seattle’s ongoing counterespionage work paid off when agents arrested Nicholas Redin, a Soviet purchasing commission agent.

By 1949, the division had grown to more than 250 agents and support staff. The office had moved to the U.S. Courthouse at 5th and Spring Street in 1940. The Seattle office quickly outgrew its space there, and by 1951, it had moved to the new Federal Reserve Bank Building at 1015 Second Avenue.

During the 1950s, criminal investigations continued to be important. With more than 100 steamship companies and 19 stevedoring companies (which were responsible for unloading a ship in port) operating in the cities of Seattle and Tacoma, interstate shipment theft was a serious concern. As a result of Seattle’s location on the northwest coast, the division also played a key role in working with the FBI’s office in Anchorage on a variety of cases. In 1958, more than half of the division’s cases were criminal investigative matters, a quarter were national security investigations, and the rest were applicant investigations and other duties.

One long-serving employee who joined the FBI in 1958 remembered what it was like for support staff in the Seattle Division during this time:

“New employees were always assigned to the mail run to pick up and deliver mail twice a day. I was also trained in radio, and ‘bad kids’ were sent to closed files for the day to file. I was asked if I wanted to go into the reception room and type. There were two of us, and we used a Dictaphone for transcribing. We literally greeted every visitor and complainant that came into the FBI. When I became pregnant…I was assigned to the ‘steno pool’ with about 35 (all female) stenos and typists. The stenos were able to take shorthand and would go to the agent’s desk to take dictation. Our FD-302s [investigative reports] had a total of nine carbon copies, and on the typewriters in those days you really did your best to be accurate.”

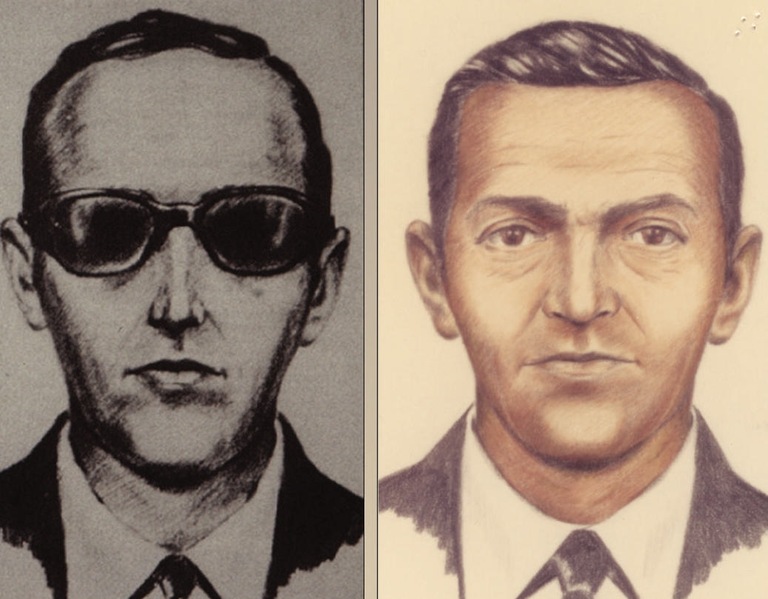

Sketches of D.B. Cooper

To help pass the time during this long and detailed work, FBI Headquarters authorized the Seattle Division to play music in the work area occupied by its clerical and stenographic forces for a 30-day trial period. Seattle was instructed to ensure that the music was “well selected and subdued” and that copyright and patent regulations were not violated.

1960s and 1970s

The transportation industry continued to have an impact on the Seattle FBI’s national security work and criminal investigations in the 1960s. In 1966, for example, Special Agent in Charge J.E. Milnes reported that the Pacific Northwest was experiencing tremendous economic and industrial growth, largely due to the expansion of the Boeing Company, which is headquartered in the city. The rise in jobs and population in the metropolitan area led to a corresponding increase of work for the Seattle FBI.

Towards the end of the decade, a rash of hijackings also began to plague air travel. One of the most famous—and still an enduring mystery—had a Seattle connection. On November 24, 1971, the day before Thanksgiving, a man traveling under the name Dan Cooper boarded Northwest Orient Flight # 305 headed to Seattle from Portland, Oregon. Before the night was over, Cooper had hijacked the plane and parachuted into the driving wind and rain with $200,000 in ransom money. A massive investigation by the FBI followed, with the Seattle Division playing a prominent role. The case remains unsolved to this day.

In August 1974, the division moved to the new federal building at 915 Second Avenue, occupying the seventh floor and half of the sixth floor.

1980s and 1990s

Like the rest of the Bureau, the Seattle FBI started to work more closely with its many partners in the 1980s and 1990s as cases began to grow more complex and crossed jurisdictional lines with increasing frequency.

One such investigation involved the so-called “Green River Killer.” On July 15, 1982, two boys discovered the body of a 16-year-old prostitute floating in the Green River. By August 16, the bodies of five more young women had been found along a one-mile stretch of the river, and the FBI was asked to prepare a psychological profile of the killer. A task force was formed by local authorities to investigate the murders; the FBI joined the investigation in the summer of 1985 after two victims were found in a suburb of Portland, Oregon. In January 1986, 10 additional FBI agents were assigned to the investigation—known to the FBI as Major Case 77, GREENMURS. On November 30, 2001, Gary Ridgway was arrested by police after his DNA had been positively identified on one of the victims. In November 2003, he pled guilty to 48 murders and was later sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. While officially admitting to 48 murders, Ridgway may have killed many more women and remains one of the most prolific serial killers in U.S. history.

In 1984, the Seattle Division joined a major manhunt for Robert Mathews, the founder of a white supremacist group called The Order. Created in 1983, the group launched a campaign of armed robbery to raise money for its plans and propaganda efforts. On June 18, 1984, members of The Order killed a Jewish radio talk show host named Allen Berg in Denver, carrying out a plan likely conceived by Mathews. Mathews became the target of an intense manhunt in November 1984 when he escaped from the FBI in Portland, Oregon following a gunfight that wounded an agent. A month later, he was tracked to a house near Smuggler’s Cove on Whidby Island, Washington. Following a 35-hour stand off, a gun battle ensued between Mathews, Seattle agents, and more than 75 other law enforcement officers. Mathews died when the house caught on fire as a result of the gunfight. The Order’s legacy of terror ended four months later when 23 members were indicted by a federal grand jury in Seattle and arrested by the FBI. Twelve members pled guilty and the others were convicted at trial of racketeering, conspiracy, counterfeiting, armed robbery, and murder. They received sentences ranging from 40 to 100 years.

During this time, the division also investigated a violent, white supremacist neo-Nazi group called the Aryan Nations. In a case called BRINKROB (because it began as an investigation into the robbery of a Brink’s armored truck), Seattle joined other FBI offices in what expanded into a racketeering/domestic terrorism probe. In 1985, 23 defendants were charged with a variety of crimes, including the robbery of two armored cars in Seattle; a $3.6 million Brinks robbery in California; counterfeiting; possible involvement in the murder of Allen Berg; and the bombing of a synagogue in Boise, Idaho.

Gary Ridgway in 2001

Beginning in June 1986, the division investigated a serious product tampering incident that resulted in two deaths. That month, a Seattle man named Bruce Nickell and another Washington state woman died after swallowing poisoned medicine capsules. After an exhaustive investigation, Seattle agents determined that Nickell’s own wife Stella—hoping to cash in her husband’s life insurance policy—had laced the capsules with cyanide and placed additional bottles of the contaminated medicine on store shelves randomly to make the deaths look like the work of a serial killer. On May 9, 1988, Stella Nickell was convicted in federal court of product tampering that resulted in the deaths—the first such prosecution in the United States. She was sentenced to 90 years in prison. In 1992, the division also successfully identified another poisoner whose tampering with off-the-shelf medicines left two people dead and another ill in a strikingly similar case (only this time, a man was trying to kill his wife but failed).

On March 20, 1988, following an anonymous tip, Seattle agents arrested Ten Most Wanted fugitive Danny Michael Weeks in north Seattle. Weeks had been serving a life sentence for murder when he escaped from the Louisiana State Penitentiary in 1986. Following his escape, Weeks committed a number of crimes. After his arrest by the Seattle Division, Weeks was convicted of abducting two women (one in Alexandria, Louisiana and another in Houston, Texas); transporting a stolen motor vehicle across state lines; and using a firearm in the commission of a violent crime.

On June 25, 1992, Seafirst Bank in the Madison Park neighborhood of Seattle was robbed by a man wearing a professional Hollywood-type disguise. Over the next four years, the man—who would come to be known as “Hollywood”—and his accomplices robbed 14 more banks, with a total take of almost $2.3 million. Their luck ran out on November 27, 1996, when they robbed a Seafirst Bank in the Ravenna area as the FBI’s Puget Sound Violent Crimes Task Force was staking out a bank nearby. A chase and gunfight ensued, but Hollywood escaped on foot, leaving behind two wounded accomplices and $1.8 million in loot. The next day, as police were responding to a report of a man hiding in a backyard near the scene, the robber killed himself and ended the mystery of his identity. Friends and family were shocked to learn that Scott Scurlock—a popular, good looking, well-educated 30-year-old resident of Olympia, Washington with no criminal record—was the Hollywood Bank Robber.

The Seattle Division also joined a major national security case at the end of the decade, as the U.S. and the world prepared to celebrate the millennium. On December 14, 1999, Ahmed Ressam aroused the suspicion of an alert border guard at Port Angeles, Washington and was arrested when it was discovered that he was attempting to enter the U.S. with components used to manufacture improvised explosive devices. Following an investigation by FBI offices in Seattle and New York, Canadian and Algerian officials, and others, Ressam admitted that he planned to bomb Los Angeles International Airport on the eve of the millennium celebrations. The investigation also revealed that Ressam had attended Al Qaeda training camps and was part of a terrorist cell in Canada. He was convicted and sentenced to 22 years in prison in July 2005.

Post-9/11

The attacks of 9/11 led to significant changes across the FBI, including in the Seattle Division, with the prevention of terrorist attacks becoming the top priority. Along with the rest of the Bureau, Seattle deepened its commitment to national security—strengthening its Joint Terrorism Task Forces, bolstering its partnerships, and improving its intelligence capabilities across all investigative programs.

It wasn’t long before the division had an international terrorism case on its hands. In July 2002, Earnest James Ujaama (aka Bilal Ahmed) was arrested and later charged with supporting terrorism, including attempting to set up a training camp for terrorists in Bly, Oregon. On April 14, 2003, Ujaama pled guilty to conspiring to provide goods and services to the Taliban in Afghanistan. As part of the plea agreement, federal prosecutors dropped charges alleging that Ujaama had plotted to establish the terrorist training camp and Ujaama was sentenced to 24 months in prison. Ujaama was later charged again after fleeing the country, pleading guilty in 2007 to various terrorism charges, including working to facilitate violent jihad in Afghanistan.

Seattle agents have also pursued environmental terrorists like members of the Earth Liberation Front and worked a range of criminal cases, from cyber crime and white-collar frauds to gangs and organized crime. Heading into the FBI’s second century of service, the Seattle Division is committed to protecting the people of Washington state from a host of major national security and criminal threats.