FBI Mobile History

Special Agent in Charge John J. Gleason

1940s

On January 13, 1947, Special Agent in Charge J.J. Gleason opened the Mobile Division. His staff consisted of 18 agents and a dozen temporary professional support staff on loan from nearby Bureau offices. The new office resided on the fifth floor of the old Federal Court and Customs House and remained there for another 40 years.

All investigative matters in Alabama prior to the creation of the Mobile office were handled by the FBI division in Birmingham. In 1947, Mobile assumed responsibility for investigations in southern Alabama and all of the Florida panhandle as far east as Jacksonville. A decade later, a newly reopened Jacksonville Division took over the northern judicial district of Florida from Mobile. Since that time, the Mobile Division has covered the 36 counties in the middle and southern federal judicial districts of Alabama.

1950s and 1960s

In its formative years, the division handled a range of criminal and national security issues, from strikers wrecking trains and other railroad property to selective service investigations. In 1951, Mobile agents arrested their first Ten Most Wanted Fugitive—Courtney Townsend Taylor, a notorious passer of fake checks. But it was the growing national focus on the denial of civil rights to African-Americans, especially in the South, that led to some of the Mobile Division’s most difficult and important work. In 1959, for instance, agents conducted important investigations into the denial of voting rights to Macon County residents. The number of election violations and other civil rights cases continued to increase into the 1960s, often in the face of strong local protests and interference. The terrorist activities of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and other white supremacist groups also were a key focus. Federal violations arising from the evolving integration of public schools in the division’s territory added to this workload.

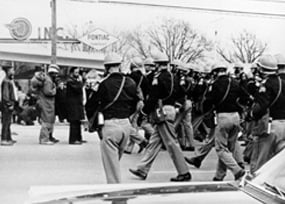

Growing violence against civil rights advocates, especially during the 1965 Selma to Montgomery protest march, became major cases for the division and the focus of national attention. The 1965 murder of civil rights worker Viola Liuzzo, however, was quickly solved, since one of the FBI’s KKK informants was in the car with the person who fired on the victim. With the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act, the division’s civil rights case load continued to increase, as did its complement of investigators.

1970s and 1980s

Bank robberies, car thefts, fugitive matters, and many other federal violations were a concern to the division as it headed into the 1970s. In 1971, for instance, Mobile personnel successfully investigated the murder of a Millry, Alabama police chief. In 1973, agents of the Phenix City, Alabama and Columbus, Georgia Resident Agencies became involved in a gun fight when a fugitive they were tracking unexpectedly emerged from his hotel room and began to fire at the agents after they identified themselves. The fugitive—John Anderson—was killed by return fire; the Bureau’s agents were unharmed. Violent kidnappings, bank robberies, and a growing number of complex gambling business and organized crime cases—including the multi-office undercover investigations known as UNIRAC (Union Racketeering)—became increasingly important during this time. The division also handled crimes on local Indian reservations.

The use of undercover operations and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act of 1970 led to many cases for the division in the 1980s. Political corruption, illegal drug distribution, bribery, fraud, and extortion cases all were put together by Mobile personnel using these and other techniques and authorities. Cases ranged from the mishandling of federal disaster relief funds and other illegal activity in the wake of devastating Hurricane Frederic in 1978…to the interception of tens of thousands of pounds of marijuana in 1981…to the conviction of a con artist who used a fake charitable foundation called “Save the Whales Foundation” to defraud local banks.

1965 Selma to Montgomery protest march

In August 1986, the division relocated its Headquarters office to One St. Louis Centre, its first move in four decades. Within months, the division saw success in a major investigation of a violation of the Hobbs Act—an anti-extortion law often used in political corruption matters. In 1987, an investigation begun two years earlier culminated in the arrest of multiple Mobile County officials and their prosecution for extortion in connection with their duties to manage clearances and permits for municipal waste removal and treatment. In the 1989 case known as ALACAP, the division worked closely with the Birmingham Division to uncover a scheme to bribe Alabama legislators into creating a dog-racing track.

1990s

In the coming years, the division worked with many other agencies on a wide variety of investigations. In 1990, for instance, an Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force case developed that involved the Mobile FBI, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the U.S. Customs Service, the Internal Revenue Service, and the Montgomery Police Department. Earlier, an undercover Mobile agent had helped the task force build a case against a number of area drug dealers with extensive foreign contacts. In one of the division’s largest and most complex investigations—informally called “the case of the invisible government”—Mobile agents also identified and put together cases against many influential businessmen who conspired with politicians and others to defraud the city, the county, and local businesses of millions of dollars. More than 10 federal and state convictions resulted from this five-year investigation.

On June 1 1992, under the Department of Justice’s Safe Streets program, Mobile personnel established the Mobile Violent Crimes Joint Task Force with the Mobile Police Department; the Prichard Police Department; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms; and the U.S. Marshals Service. Within a year-and-a-half, the task force made more than 227 arrests. Many convictions arose from its investigations of local offshoots of the Crips and Disciple gangs, carjackings, and even a kidnapping by a pair of violent fugitives.

In 1992, the division launched another major investigation called “Soft Assets” involving a network of fraudulent insurance and reinsurance companies based in multiple countries. The network operated individual insurance agencies under it much like a Ponzi scheme, collecting insurance premiums with a promise to pay on claims, yet defaulting at a later point, hiding its assets abroad, and claiming bankruptcy in the United States. In 1993, the principals in the case were arrested and eventually convicted, earning significant jail time and tens of millions of dollars in fines.

Civil rights cases continued, and in the mid-1990s, a large number of church burnings raised national concern. In 1997, Mobile investigated two such burnings that occurred around the same time and within close proximity. In cooperation with numerous other agencies, agents identified and arrested five suspects. Further investigation built an even more complete case against them and led to several more guilty pleas and convictions on civil rights charges.

The next year, the division faced another major hurricane. As Hurricane Georges headed towards Mobile, FBI personnel kept the office operational and communications working even as city power failed and the storm passed directly over the area. Following the storm, the division investigated a number of fraud matters involving unscrupulous individuals trying to take advantage of the disaster.

Post-9/11

Following 9/11, preventing terrorist attacks became the top priority of the FBI. The Mobile Division responded to this mandate, working through its Joint Terrorism Task Force, its newly created Field Intelligence Group, and other resources.

In September 2002, the office assisted a large task force from the Washington, D.C. metropolitan region in investigating the sniper attacks that terrorized that region, checking out a related local murder that ultimately played a key role in solving the case.

On February 2005, Debra Mack was named the special agent in charge of the Mobile Division, one of first two African-American females to ever head an FBI field office. She served until 2009.

In the fall of 2005, the region was hit hard by yet another storm—Hurricane Katrina. Many FBI employees in Mobile were among those who lost their homes, but the office was back in full operation within a week.

In recent years, the division has tackled a rising number of child pornography and child predator cases as well as a variety of other cyber crimes. Extortion, fugitive matters, white-collar frauds, and many other crimes and national security concerns have also been pursued by the Mobile office using its growing suite of post 9/11 intelligence capabilities.

Today, the more than 100 special agents and support staff in the Mobile Division—including its five resident agencies in Auburn, Dothan, Monroeville, Montgomery, and Selma—work to protect communities in 36 counties in the southern half of Alabama from a full range of national security and criminal threats.