FBI Miami History

Early 1900s

The exact date when an FBI office was opened in Miami is unknown, but we do know that one was operating by October 1924, with L.E. Howe serving as special agent in charge. Soon after, the office was closed and made a resident agency of the Jacksonville Division.

The early Miami Resident Agency pursued a wide-range of investigations, from automobile theft to interstate prostitution. In 1929, it made national news when its investigation of Chicago gangster Al Capone led to his arrest for skipping out on a bench warrant. Capone had claimed that he ignored a subpoena because he was laid up with pneumonia, but Miami agents learned he had been to the race track and taken a boating trip, among other excursions.

In late 1936, FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C. decided that Miami needed its own field office because of its growing caseload and population. In January 1937, a division was re-established with Robert L. Shivers as special agent in charge. The Jacksonville office was then made a resident agency under Miami and operated as one for the next two decades.

During this time, Miami agents handled a number of public corruption and organized crime investigations (because of Florida’s popularity as a vacation spot, many gangsters visited the state) as well kidnappings and interstate prostitution. One notorious case took place in 1938, when five-year-old James Cash was kidnapped and killed. At the request of local authorities and the Cash family, the Miami Division investigated the incident and turned over information and evidence to its partners. A mere 19 days after the kidnapping, Franklin Pierce McCall was captured and pled guilty to the crime.

1940s and 1950s

The onset of World War II in 1939 and U.S. entry into the conflict in 1941 meant a vast increase in work across the Bureau—including in Miami, which was a major port and a southern economic hub.

The division played an important role in one of the most famous war-time cases. In June 1942, two groups of Nazi saboteurs came ashore in the U.S. after being dropped off by German submarines. The first group landed in Long Island, New York; the second in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. FBI agents from the Miami Division located explosives and supplies that the Nazis had buried on the beach. The continuing investigation developed information that helped many other divisions as they tracked the saboteurs from Florida to Chicago and New York, where they were arrested within days. Throughout the war, the division continued to receive a great many reports of possible enemy landings, flashing lights, and submarine sightings from a concerned public. Each one was evaluated and run to ground.

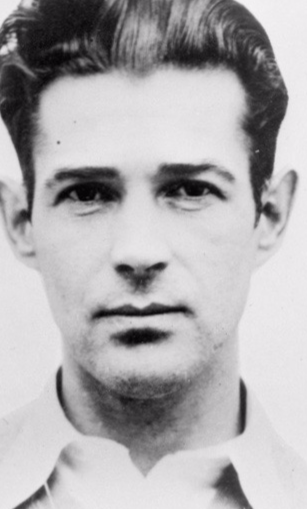

Mug shot of Al Capone in 1929

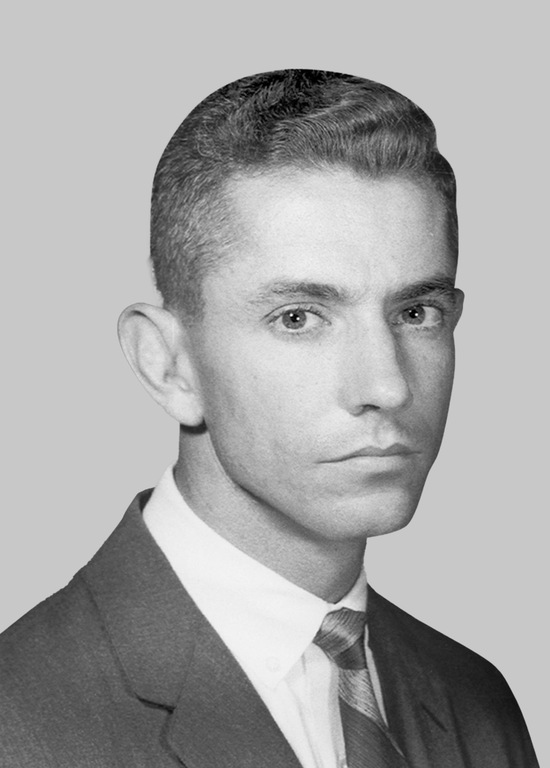

Gerhard Arthur Puff

By the early 1950s, Miami was staffed by more 150 special agents and support personnel. Resident agencies were located in Daytona Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Jacksonville, Lakeland, Orlando, St. Augustine, St. Petersburg, Sarasota, Tampa, and West Palm Beach.

The division continued to investigate a wide range of crimes. In 1952, Miami agents apprehended Ten Most Wanted Fugitive George Heroux, who was sought for an alleged bank robbery in Kansas. Clues obtained during the investigation also led to the capture of another Top Ten Fugitive—Gerhard Arthur Puff—in New York.

Because of its proximity to Cuba, the division has long been responsible for liaison (at least before communist revolution in the country in 1959) and cases involving the island nation. In 1950, for example, Lt. Sigfredo Diaz Biart, Chief of the Cuban Bureau of Investigation, visited Miami to observe the Bureau’s firearms training. Later, as revolution brewed, Miami agents thwarted an attempt to deliver stolen government submachine guns to revolutionary forces in Cuba in violation of U.S. neutrality laws.

1960s

During the 1960s, the Miami Division investigated cases of fraud, bribery, extortion, illegal gambling, and theft. A growing number of cases involved Cuba. Whether it was a hijacked plane flown in the direction of Havana or potential terrorist attacks against Cuba from groups operating on American soil—such as the MIRR (the Movimento Insurreccional de Recuperacion Revolucianaria) in 1964 and 1968—the division was kept busy with investigations involving its island neighbor.

In one case, a Bureau agent who was operating undercover prevented a scheme by a Cuban national that involved kidnapping an anti-Castro leader to discredit the United States. The plan was to put the leader in a boat loaded with arms and ammunition. Upon his arrival to Cuba, he would be arrested and charged with directing an invasion against the Cuban people for the U.S. government.

In 1966, the division investigated a case involving another foreign nation. On November 2, the Bureau learned of a plot to destroy a railroad bridge in the Republic of Zambia later that year. An American citizen named Franklin Boyd Thurman had been offered $50,000 as payment for the job. Miami agents located Thurman in a local motel and later uncovered evidence of his plan and associates. Thurman pled guilty, and another defendant was convicted.

Violent crime and extortion were also on the rise in Miami during this period. In 1963, Miami agents arrested Jerry Clarence Rush, a Ten Most Wanted Fugitive, who was sought for unlawful flight to avoid confinement, assault with the intent to murder, and bank robbery. The next year, the division prevented John Wesley Davis and Joel Leo Vedder from bombing the Florida East Railway by disarming the bomb before it exploded. And in August 1969, Miami agents arrested Henry Kiter, Jr. only two days after learning of his threat to blow up Delta Airlines planes unless he was paid $300,000.

In December 1968, the Miami Division joined one of the strangest cases in FBI history. A 20-year-old college student named Barbara Jane Mackle, who belonged to a wealthy Florida family, was kidnapped from Decatur, Georgia, where she was recovering from the flu with the help of her mother. Mackle was taken to a wooded area east of Atlanta and essentially buried alive in a sturdy box about 18 inches below ground. The box included vents, food, water, a light, and a fan. The kidnappers—later discovered to be Gary Steven Krist and Ruth Eisemann-Schier—demanded a ransom of $500,000, which the family agreed to pay. During the first attempt to hand off the ransom money, police accidentally drove by, and the kidnappers ran off. FBI agents found the kidnappers’ car nearby, which included their identities and addresses. The second hand-off was successful, and the FBI was given general directions to the location of Mackle. Following a massive search, Mackle was found unharmed. Both kidnappers were soon captured and sent to prison.

1970s and 1980s

White-collar crime, corruption, and fraud were the primary focus of the Miami Division during this time. In 1971, for example, the division found that David Marder and Morris Engel were involved in a large-scale bookmaking operation. This information led to simultaneous arrests of a dozen people, including two mobsters, as well as the seizure of voluminous gambling records and $60,000 in U.S. currency.

Perhaps the most important case pursued by the division in the 1970s was an investigation called UNIRAC, short for union racketeering, which touched a number of FBI offices. In June 1978, 22 labor union officials and shipping executives were indicted in Miami for kickbacks, embezzlement, and other illegal activities surfacing from undercover investigations into organized criminal racketeering. Eventually, more than 110 convictions were recorded—including that of Anthony M. Scotto, a longshoreman union leader and organized crime figure.

In the late 1970s, the division launched an undercover sting code-named MIPORN (short for Miami pornography) that targeted dealers in child pornography. Miami agents formed a bogus porn business and traveled around the nation meeting various players in the business. In early 1980, the operation culminated in the arrest of 45 top pornographers across the country.

Later that year, economic troubles and internal strife in Cuba led that country to announce that anyone who wished to leave the island could do so. This resulted in the “Mariel Boatlift,” a mass exodus of more than 100,000 Cuban refugees into the U.S. from April to October. Miami personnel played a key role in shaping the American response to the immigration, working with national policy advisers to develop and create a unified national security screening procedure for the Cubans who arrived in Florida.

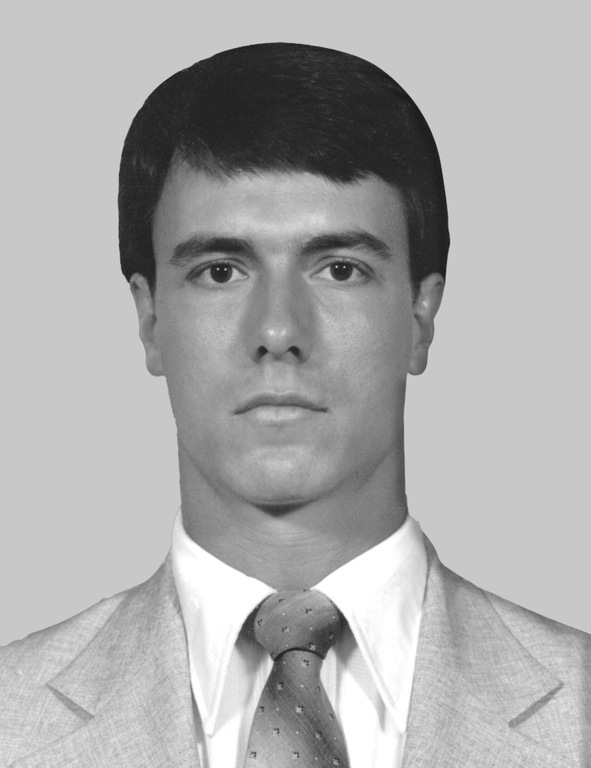

On April 11, 1986, tragedy struck Miami when Special Agents Jerry Dove and Benjamin P. Grogan were killed during a gun battle with two robbery suspects. Five other agents were also injured; each was awarded the FBI Star for sustaining serious injury in confronting criminal adversaries.

FBI Special Agents Benjamin Grogan

Special Agent Jerry Dove

The effort to fight organized crime and fraud continued, often blending with an increased emphasis on drug enforcement. In 1983, the FBI was authorized to investigate a number of drug-related matters in conjunction with the Drug Enforcement Administration. Many successful cases followed. In May 1987, for example, Miami agents seized a 46-foot yacht containing 613 kilograms of cocaine—at that time the largest direct seizure of cocaine by the FBI. In October of that same year, the division uncovered the “stash house” of the Benitez Group, which played a major role in the transportation and distribution of cocaine and marijuana in the Miami area. In uncovering this stash, agents found more than $3.8 million in cash hidden in false closet ceiling compartments. In 1988, the division’s TRAVESURA case identified and neutralized members of the Dangond Columbian Drug Organization, responsible for the importation and distribution of multi-ton shipments of cocaine into the U.S. The investigation led to 13 convictions and forfeitures of cash and other assets, including a 400-foot freighter that had been used to import an estimated 4000 kilograms of cocaine into the country.

In 1987, the division helped handle the national security implications of Pope John Paul II’s visit to the United States. Miami was his first stop, and President Reagan met him there. The visit was designated a special event by FBI Headquarters, and the Miami Division prepared to respond to any incidents involving the president or the pope, in cooperation with the Secret Service and local and state law enforcement.

Also in 1987, following a massive investigation led by the Miami Division, two co-founders of a company called ESM Government Securities, Inc., were sentenced to prison for their roles in a $320 million bank fraud and embezzlement case, the largest in FBI history at the time. Three other ESM executives were also convicted in the case.

1990s

Miami continued to be a hotbed of illegal drug activity into the 1990s, and the division focused significant resources on drug-related cases. Millions of dollars in drug money and tens of thousands of kilos of cocaine were seized in various investigations. One case—called CRACKERJACKS—was launched in January 1994 based on information from the Metro-Dade Police robbery unit about a group involved in numerous jewelry store robberies in the Miami area. This group, which was funding a drug distribution network with money made from the robberies, took control of local drug pockets and established their own salespeople, enforcers, and distributors of cocaine, heroin, and crack cocaine. The investigations concluded that an average of $100,000 in weekly drug sales were generated from 1986 to 1993. A total of 66 individuals were charged in a series of federal indictments.

During this time, corruption, murder, theft, fraud, espionage, and even terrorism cases were also investigated by special agents in Miami. In March 1991, for example, an undercover operation was begun to identify people involved in a series of bombings and attempted bombings begun in the late 1980s that targeted businesses and persons sympathetic toward normalizing relations with Cuba. The investigation was called FREIGHTBOM, and it led to the identification of potential Cuban intelligence officers, the prevention of three terrorist bombings, and the identification of the cell behind the attacks.

In another major national security case, Miami agents arrested 10 members of a Cuban spy ring operating in southern Florida in September 1998. The ring was targeting the region’s major military installations, including the U.S. Southern Command and the local Cuban émigré community. Three of those arrested were Cuban intelligence officers who had entered the U.S. and assumed the identities of deceased American children. The Naval Criminal Investigative Service provided significant assistance in the investigation.

In 1999, another investigation resulted in the arrest of 21 suspects charged with drug trafficking, money laundering, and firearms violations in the Dade County area. The case was conducted by the Miami Division’s multi-agency Safe Streets Task Force.

Post-9/11

After the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the Miami Division went through massive changes along with the entire Bureau, making preventing terrorist attacks its overriding focus.

The Joe Cool fishing boat

In recent years, the division has pursued several major terrorism cases. On November 22, 2005, for example, a federal grand jury in Miami indicted Jose Padilla on charges of conspiring to murder, kidnap and maim persons overseas and providing material support to terrorists as part of a North American terrorist support cell. Padilla had been arrested in Chicago in May 2002, but Miami supplied significant investigative work in the case. In 2006, seven Florida men were also arrested on charges that included conspiring to provide material support to al Qaeda and conspiracy to levy war against the U.S. by discussing and planning attacks on the Sears Tower in Chicago, the FBI building in Miami, and other federal buildings in Florida. Five men—including Narseal Battiste, the group’s leader—were convicted on a variety of charges in May 2009.

Miami agents pursued a full range of criminal investigations as well, including cases involving health care fraud, gangs, and even bank robberies. In late 2005, for example, one of the largest heists in Florida history took place when $7.4 million was stolen from customs agents at Miami International Airport. FBI agents worked with the Miami-Dade Police Department and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to identify likely suspects—including a security guard at the airport—and put them under surveillance. When a reward was offered, a cooperating witness came forward and agreed to wear a wire while talking with the suspects. In the meantime, a rival gang kidnapped one of the thieves. By early 2006, four men were charged with armed robbery, and three kidnappers were charged with hostage-taking. In 2007, Miami agents also solved a case involving the murder of four crew members aboard a fishing boat called the Joe Cool.

Heading into the FBI’s second century of service, the Miami Division continues its work to protect Americans from domestic and international terrorism, espionage, cyber crime, public corruption, and a range of other crimes that undermine the safety and security of the nation.