FBI Knoxville History

Early 1900s through 1940s

From its earliest days, the FBI has conducted significant investigations in the state of Tennessee—from the successful pursuit of thieves who made off with over a million dollars worth of materials from the Old Hickory Powder Plant in Nashville…to the arrest of George “Machine Gun” Kelly in Memphis.

By 1937, crime had grown to such an extent that the Bureau realized that it needed two field offices in the state. Although the Bureau’s office in Tennessee had been in Nashville, it was decided that new offices should be opened in Memphis and Knoxville and that the office in Nashville should be closed. By May 1, Richard B. Hood was designated acting Special Agent in Charge, and the new Knoxville Division was opened for business in the Hamilton National Bank building.

Knoxville agents and support personnel were soon pursuing important cases. In June 1937 they investigated the kidnapping of a Chattanooga police officer and identified the perpetrators, who were arrested in Tampa. In 1938, agents were drawn into a firefight with Thomas Jefferson Whitehead when he resisted arrest on a motor vehicle theft charge. Whitehead was killed, and no agents were injured.

By September 1942, the Knoxville Division had established its first two resident agencies. These satellite offices were located in Johnson City and Chattanooga, Tennessee.

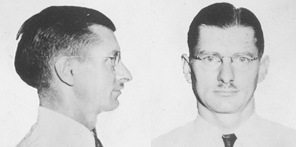

Richard B. Hood

Waldemar Othmer

With World War II on the horizon, Knoxville Division’s national security responsibilities began to increase. The Division, for example, inspected local plants involved in the war effort to prevent sabotage and espionage. In 1944, Knoxville agents arrested Waldemar Othmer, who confessed to spying for Germany before the U.S. entered the war. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

1950s and 1960s

With the end of the war, new threats were on the horizon for Knoxville. In the early 1950s, the Division found itself investigating more and more activities of the Ku Klux Klan and its offshoots as well as chasing bank robbers, kidnappers, and fugitives from justice. Organized crime was also on its list of priorities. In 1964, for example, Knoxville agents investigated Teamsters leader Jimmy Hoffa for jury tampering; Hoffa was convicted and served several years in jail for the crime. Hoffa went missing in 1975, and he is presumed dead.

National security, though, remained important during this period with the onset of the Cold War and the discovery of extensive Soviet penetration of the U.S. government. Civil rights cases also grew more prominent. In 1958, for instance, Knoxville investigated a cross-burning on the lawn of a family of Gypsy heritage. And in 1960, the Division pursued one of its most sensitive cases when Chief Deputy Sheriff George Sartin and his brother—both of the Roane County Sheriff’s Office—were charged with arresting William Thomas Ferguson without a warrant and subsequently abusing him. Both men were convicted in 1962.

1970s

The cultural strains of the late 1960s continued into the 1970s. Knoxville faced many of these issues. In 1972, the office worked closely with the Atlanta Division when a Southern Airways flight from Memphis was hijacked. Other agents began to develop their ability to build undercover cases. In 1972, for instance, one undercover operation led to the arrest of four subjects who were illegally distributing pornography. Agents used new authorities for electronic surveillance to pursue illegal gambling operations in 1974 and extensive fraud by companies supplying coal to the Tennessee Valley Authority in 1976.

The Knoxville Division also worked to enhance Bureau investigative resources. In a September 1976 memorandum to the Director, the Knoxville Special Agent in Charge indicated that the office had two bloodhounds and a Bureau handler who had achieved a high degree of success in trailing criminals and lost persons. The memo explained that the dogs were available to all FBI field offices on request and that arrangements could be made to expeditiously transport them and their handler to any place in the continental United States.

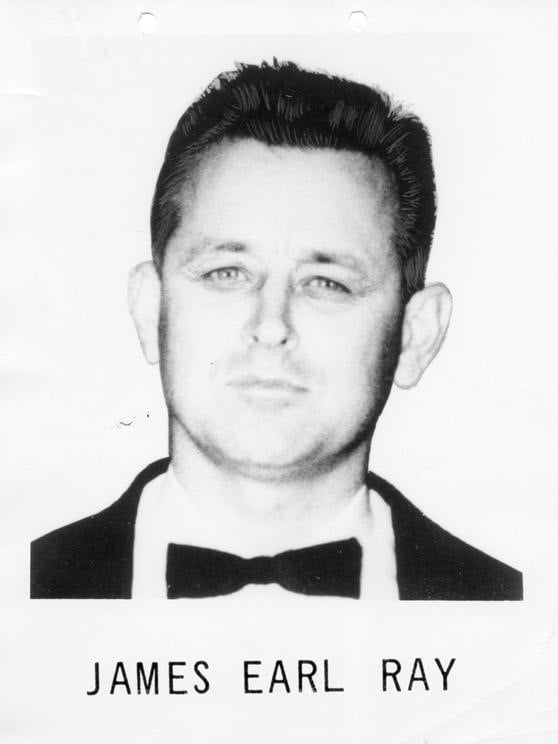

Bank robberies and fugitives remained important concerns, but the office conducted important investigations in other areas. In 1977, a Knoxville case led to a 35-count indictment against a member of the Knox County Board of Commissioners for selling his vote regarding a landfill site; the commissioner was found guilty on all counts. Agents also pursued James Earl Ray, the assassin of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., when he and other inmates escaped from a Tennessee state prison. Ray was added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list and was quickly captured near New River, Tennessee. One of Knoxville’s bloodhounds, a dog named Sandy, helped locate him. For several years, Knoxville agents worked with a number of other law enforcement agencies in an undercover operation targeting a large automobile theft ring operating around Chattanooga. The operation resulted in 31 federal convictions and hundreds of thousands of dollars in recovered property.

1980s and 1990s

In the late 1970s, Knoxville continued developing its Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) and hostage negotiation skills. This expertise was put to effective use in July 1979 when an armed gunman took a Chattanooga police officer hostage and again in May 1980 when prisoners at the Greene County jail took a deputy hostage. In both cases, Bureau intervention led to the hostages being freed and the criminals being captured. The Division’s SWAT team continued to play an important role in Knoxville cases and in others around the nation. In 1987, the team traveled to Atlanta to assist in quelling a major riot at the city’s federal prison.

The 1982 Worlds’ Fair, Expo ’82, was held in Knoxville and received extensive support from the Knoxville Division. Specifically, the Division assisted the Knoxville Police Department with pre-planning and joined with many other federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies in providing security for the event, which brought more than 1,500 international visitors from 22 countries. On May 31, a French artifact on loan from the Louvre was stolen at the fair. Knoxville recovered the artifact and returned it to the French Pavilion less than a month after the initial robbery.

James Earl Ray

Undercover investigations by Knoxville continued to be successful. In 1986, a three-year investigation called MAYBAN led to the convictions of a number of individuals for bankruptcy fraud. MACH TENN, another undercover operation, led to the arrests of law enforcement officers in Scott and Claiborne Counties for a series of abuses of their authority. And the REHEAT case led to dozens of prosecutions for major property thefts conducted with the collusion of corrupt cops.

Knoxville Division also pursued major drug probes like the 1998 task force investigation named “Operation Tridown” that disrupted a cocaine distribution ring. Chattanooga police, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the FBI, the Hamilton County Sheriff’s Office, and the IRS were all involved.

Post-9/11

Since 9/11, Knoxville has made national security its top priority, creating a Joint Terrorism Task Force with Tennessee law enforcement and other federal representatives. It has also instituted a Field Intelligence Group, or FIG, to spearhead the acquisition, analysis, and dissemination of intelligence.

Major crimes, especially color of law/political corruption, remain important priorities. In January 2006, for example, Knoxville’s participation in a national initiative named “Operation Broken Wheels” was announced. The Division’s work led to the prosecution of Tennessee Department of Safety officials for bribery, transportation of illegal aliens, and the issuance of fraudulent driver’s licenses. That same month, another investigation led to the indictment of a Roane County judge for extortion and money laundering.

As the FBI heads into its second century, the Knoxville Division continues to make significant contributions to the safety of Tennessee, to the integrity of its public officials, and to the work of the Bureau across the nation.