FBI Honolulu History

1930s

Our first office in Honolulu was opened in April 1931 to establish a presence on the Hawaiian Islands—then a U.S. territory— mostly to handle immigration and fugitive matters but also to address concerns about rising Japanese militarism in the Pacific.

Joseph P. MacFarland was the first special agent in charge and the only Bureau employee stationed in Honolulu. This early office was closed in 1934 only to reopen in 1937 under MacFarland. It closed again the next year, but reopened for good under the direction of Special Agent in Charge Robert L. Shivers in August 1939.

1940s

Special Agent in Charge Robert L. Shivers. Pearl Harbor attack photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Shivers immediately began assessing the possibility of Japanese spies and saboteurs working against the U.S. in Hawaii—and developing Bureau plans in case war broke out. Even before the U.S. entered World War II, for example, the office was investigating German-born Bernard Julius “Otto” Kuehn, a resident of Honolulu who first aroused our suspicions in 1939. Although we had no definite proof, Kuehn was indeed spying, using an elaborate system of signals to inform the Japanese Consulate about the comings and goings of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Honolulu Division investigation discovered the true extent of his spying, and he was arrested the next day. He was later convicted of espionage and deported.

The attack on Pearl Harbor had taken the lives of thousands of American sailors and severely damaged U.S. sea power. The Honolulu Division provided one of the earliest notifications to the mainland of the aerial assault from its newly installed radio facility. Shivers soon became a central figure in all of the civil security measures taken in Hawaii. His office tasked the local police to protect the Japanese Consulate from revenge acts and worked around the clock to deal with the aftermath of the bombing and onset of war.

With full support from Director Hoover, Shivers and his team in Hawaii sought to protect the rights and freedoms of all people in Hawaii, including those of Japanese ancestry. While more than 110,000 individuals of Japanese descent from the West Coast were relocated inland during World War II, less than one percent of the 160,000 persons of Japanese heritage in Hawaii were interred.

The Honolulu office had opposed detaining anyone without just cause, arguing that the Bureau and military intelligence forces had a clear picture of their domain and knew who was a potential threat and who wasn’t. Despite the very low percentage of people of Japanese ancestry interred in the islands, not a single act of enemy-directed sabotage was committed in the region following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

1950s and 1960s

As World War II came to an end and Special Agent in Charge Shivers announced his retirement, 33 special agents and support staff members worked in the Honolulu Division. They began to direct their attention towards cases of extortion, bank robbery, and gambling violations, even as counterintelligence remained important in the early years of the Cold War.

As a way-station to Asia, the Honolulu Division worked to prevent the popular tourist destination from becoming a safe haven for criminals by apprehending fugitives from throughout the United States. In one case, agents found and arrested a pair of parole violators from Massachusetts while they attempted to rob a bank on Waikiki Beach. In another case, Honolulu agents arrested Top Ten Most Wanted fugitive Ronald Eugene Storck while he was aboard a yacht. Storck was wanted for a triple homicide committed in Pennsylvania. Storck was the first Top Tenner to be arrested in the division’s territory.

Of the many bank robbery cases the Honolulu Field Office investigated during this period, one of the most notorious involved four subjects who had taken a local bank manager’s family hostage, then used that leverage to gain access to the bank safe. The bank manager and his family were released unharmed, and the subjects fled with $89,000. All four subjects were apprehended and charged with the crime.

Early Honolulu field office

1970s

Illegal gambling operations and bank robberies remained priority crimes investigated by the Honolulu Division during the 1970s. In one joint operation with the Honolulu Police Department, 78 search warrants were executed, leading to the seizure of a large amount of cash and voluminous gambling records. With this and other evidence developed in the investigation, 47 individuals were charged with conducting an illegal gambling operation. The records seized were turned over to the IRS for review, and more than $1.3 million in tax levies were served on the subjects as well.

In one early 1970s case, a Honolulu Division investigation led to significant breaks in a violent bank robbery. One of the criminals—Earl Lum—was killed in the firefight that erupted between Honolulu law enforcement officers and the robbers, while the rest of the criminals fled the scene. An investigation by Bureau agents and Honolulu police led to the arrest of six others who had been involved in Lum’s bank robbery.

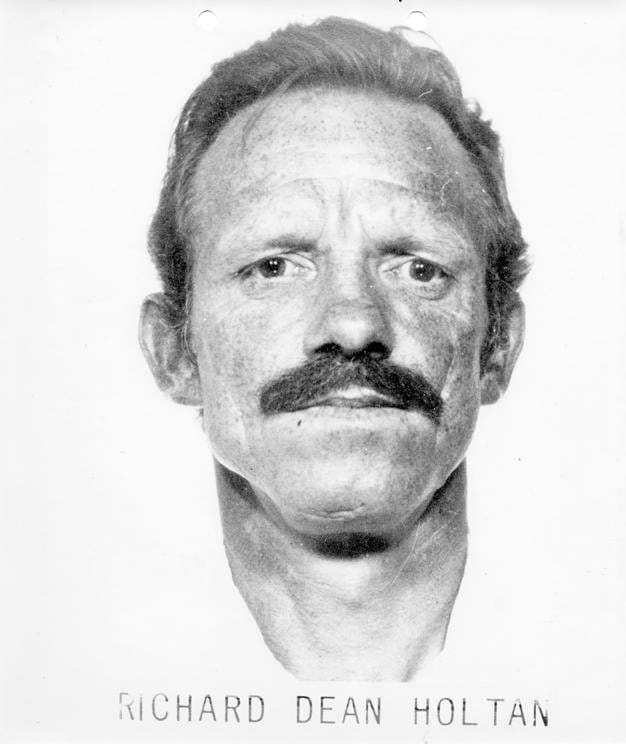

In 1975, Honolulu Division agents apprehended another of the FBI’s Top Ten Most Wanted fugitives, Richard Holtan, who was wanted for bank robbery and murder.

The division continued to work closely with local police forces to seek out and stop criminals. One example was Operation HUKILAU (a Hawaiian word meaning “going fishing”). In 1977, Honolulu agents helped the Honolulu Police Department establish a false storefront to recover stolen items and stop petty thefts. This year-and-a-half-long program was so effective that it resulted in the solving of more than 500 burglary, theft, and robbery cases. A total of 22 people were indicted on federal charges and 108 on local charges. A similar operation occurred in the Washington Field Office around the same time.

The Honolulu Division was not only responsible for protecting the Hawaiian Islands, but also all American territories in the Pacific Ocean. To that end, a permanent Resident Agency was established in Guam in 1975, becoming the FBI’s westernmost investigative office.

1980s and 1990s

The Guam Resident Agency quickly tackled a number of difficult investigations, including several cases of corruption. By 1982, enough evidence had been gathered to begin a probe of senior members of the government in Guam suspected of defrauding the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Stamp Program. As a result of the investigation, 17 individuals were charged with conspiracy, mail fraud, and other crimes in a 117-count indictment.

In 1983, the Honolulu Division opened another investigation into fraud and corruption by government officials in Guam. The undercover phase of this operation was known as Balloon Fish and resulted in the conviction of 11 individuals, six of whom were official members of the government of Guam. Balloon Fish also resulted in a spin-off investigation of the governor of Guam, Ricardo Jerome Bordallo. In 1987, Bordallo was convicted on corruption charges after a 22-day trial.

During this time, the Honolulu Division also joined with the CIA, the IRS, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the U.S. Attorney’s Office, and other partners in two-year investigation of Ronald Ray Rewald. Using a “Ponzi” scheme, Rewald had defrauded over 400 investors out of $22 million. He was eventually found guilty of 96 counts of fraud.

The Honolulu Division also focused on major drug smuggling and international crime organizations in the late 1980s, building upon interagency cooperation from previous years and participating in several joint investigations with U.S. Customs, the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Navy, and the Drug Enforcement Administration. The division also helped train multi-national police forces from agencies across the Pacific Ocean and developed the first Pacific Training Initiative. More than 52 police officers from Guam, Saipan, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, Palau, Nauru, and Vanuatu completed the first class and returned home, sharing what they learned with their respective police forces.

Post-9/11

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, the Honolulu Division went through substantial changes along with the rest of the Bureau, making preventing terrorist attacks its overriding priority.

Meanwhile, the Honolulu Division continued to address criminal threats—including the illegal drug trade that was wreaking havoc in the region. Drugs such as crystal methamphetamine, for example, were a contributing factor in more than 90 percent of child abuse cases in 2002. Drug sales in Hawaii were also believed to fund terrorism and support militant groups and criminal gangs throughout the Pacific region.

To that end, the Honolulu Division assigned a special agent and an analyst to the Joint Interagency Task Force West (JIATF West) in Honolulu. JIATF West provides U.S. and global military and law enforcement partners with the intelligence necessary to detect, disrupt, and dismantle drug-related transnational threats in Asia and the Pacific. Task force members include uniformed and civilian members of all five military services, as well as representatives from the intelligence community, federal law enforcement agencies, the Australian Federal Police, and the New Zealand National Police.

In June 1999, Hawaii was designated a high intensity drug trafficking area, or HIDTA. In 2004, Special Agent in Charge Charles Goodwin reported to Congress that the prevention of illegal drug sales would be one of the Honolulu office’s top priorities. Investigations by the division have found links between drug sales and organized crime throughout Asia, making international cooperation crucial in stemming drug trafficking in Hawaii.

The division has launched some major investigations in recent years. In one case that demonstrated its growing intelligence capabilities, the Honolulu Field Intelligence Group helped catch a former defense contractor trying to sell B-2 stealth bomber secrets to foreign governments. In another case, the division helped put behind bars a factory owner who had enslaved more than 250 garment workers in American Samoa.

From its unique geographic vantage point, the Honolulu Division continues to be committed to building on its legacy of protecting America from both domestic and global threats.