FBI Washington History

Early 1990s through 1930s

The FBI first opened an investigative office in Washington, D.C. in the years before J. Edgar Hoover was named Director. Often confused with Bureau Headquarters in the nation’s capital, Director William Burns found it necessary to inform his Special Agents in Charge in March 1922 that “the Washington Bureau office is a regular field Bureau office, therefore, when investigation is requested to be made” within its jurisdiction, the requests should be made to the Special Agent in Charge, not to Bureau Headquarters.

See a list of the known leaders of the Washington Field Office

W.G. Walker was the Special Agent in Charge at that time, and the Washington Field Office—commonly called WFO—was responsible for investigations in Northern Virginia, the District of Columbia, and several counties in Maryland. The office later began handling cases in the state of Delaware.

By 1924, WFO had 34 special agents and 24 open cases. Among the agents were two women—Jessie B. Duckstein and Alaska P. Davidson, two of the first three female agents known to serve in the Bureau—as well as two African-Americans—Arthur L. Brent and Ruvello Rynaldo Gray. All left the Bureau later that spring when Director Hoover dramatically cut the rolls to clean house following the Teapot Dome scandal.

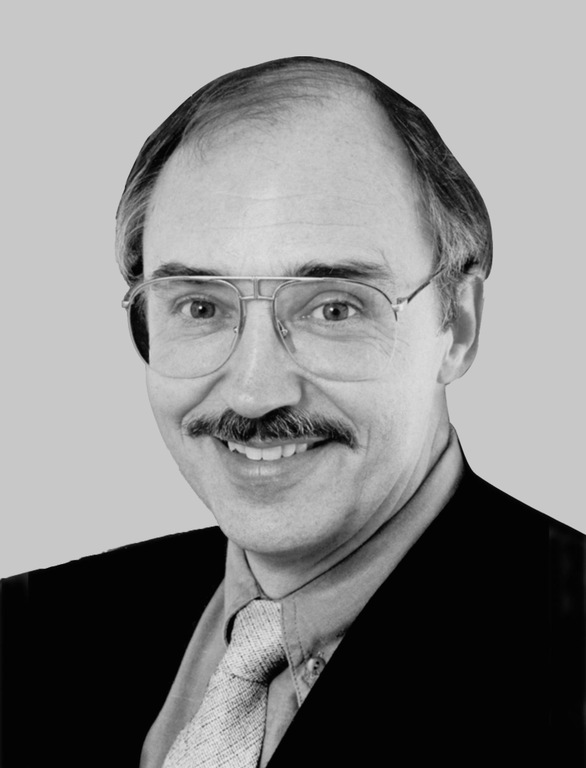

Special Agent in Charge W. G. Walker

Special Agent Alaska P. Davidson

From these earliest days, WFO tackled a wide range of responsibilities. Agents investigated domestic terrorism, interstate prostitution violations, automobile theft, white-collar crime, and many other types of cases. Since the headquarters of most other government agencies are located in the nation’s capital, WFO ultimately became involved in most of the FBI’s applicant investigations.

By 1937, the Division was handling so many cases that Headquarters approved the creation of a field office in Richmond to take over some of the office’s case load in Virginia and, several months later, a Baltimore Field Office was set up to take over some of the investigations originating in Maryland as well as those in Delaware. Despite these changes, WFO remained one of the busiest offices in the Bureau.

That same year, the office helped pioneer the implementation of new operational technology for the Bureau. In 1937, one of the FBI’s first two radio trucks—mobile vehicles equipped with radio for surveillance and case communication—was field tested by WFO. This vehicle was used in kidnapping investigations and the hunt for Nazi saboteurs who landed in the U.S. during World War II. In 1938, the Bureau’s first mobile, two-way radio was also put into service in the office.

1940s and 1950s

World War II increased the workload of WFO, adding significant national security responsibilities. Counterespionage, of course, was a concern, but so too were federal employees with Nazi or communist connections. By 1941, WFO was handling more than 5,300 national defense cases and more than 6,100 applicant matters, along with another 1,100 general investigations.

WFO agents played significant roles in many major cases during the war. For instance, they took into custody George John Dasch—the leader of a band of Nazi saboteurs who landed on U.S. soil in 1942—and gathered information from him that led to a nationwide manhunt for his confederates. The office also played a significant role in protecting wartime secrets in the nation’s capital and surrounding area.

With the end of World War II, counterintelligence continued to be a priority for the FBI, and WFO investigated thousands of leads emerging from the information supplied by Elizabeth Bentley, a courier for Soviet spy rings in wartime Washington, D.C. Further investigations and the cryptographic breakthrough known as Venona helped the U.S. Intelligence Community and its European partners identify more than 170 people who had assisted Soviet intelligence. As a result, the U.S. government was able to cut off these spies’ access to national secrets, allowing the FBI—especially its Washington and New York offices—to move more proactively against the threat of Soviet intelligence.

A WFO special agent on the shooting range in the 1940s

Operator at the WKGB 770 radio station

Counterintelligence remained a focus of WFO through the 1950s as new issues arose across the nation. Its agents worked with the U.S. Secret Service and other agencies, for example, to investigate the attempts of Puerto Rican nationalists to assassinate President Truman in 1950 and members of Congress in 1954.

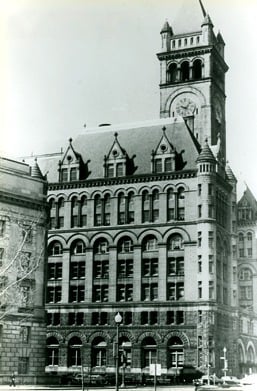

Securing appropriate facilities for WFO personnel was also an issue during this time. For years, WFO had moved back and forth from one office to another, including several stints when it was co-located with FBI Headquarters. Beginning in 1951, the office was on the fourth and fifth floors of the Old Post Office Pavilion, two blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Department of Justice. The Pavilion had its share of problems, and the government debated for years whether to renovate or condemn the building. The point was driven home on October 10, 1956, when hundreds of federal employees—including those of WFO—were stunned by a loud bang caused when a thousand pounds of clockwork in the tower of the building came crashing down onto the ninth floor. No employees were seriously harmed, but debate about the future of the building continued. WFO remained in the Pavilion until 1977.

By the end of the 1950s, WFO was staffed by more than 450 special agents and 230 support employees. It handled a yearly average of 900 criminal cases, 1,200 national security investigations, and 1,200 applicant and other matters.

1960s and 1970s

Throughout the 1960s, WFO continued to investigate a wide array of crimes. These investigations brought the office into contact—and sometimes conflict—with the many protest movements of the day. In 1965, for instance, a civil rights protest was staged at WFO’s fifth floor main entrance. The protesters, however, said that the Bureau was not the target of their complaint—they wanted the Department of Justice to increase its civil rights work in the aftermath of the Selma March.

In the early 1960s, WFO joined with its partners in investigating the kidnapping and murder of a seven-year-old boy named Michael Condetti. Following a massive manhunt, Joseph “Whiskey Joe” Haverman Alvey was arrested for the crime. In 1962, Alvey was sentenced to life in prison.

As the reaction against the Vietnam War increased and some elements of 1960s’ protest movements turned violent, WFO faced a number of difficult investigations. One such terrorist offshoot of these earlier movements was the Weather Underground. In 1969, members of the Students for a Democratic Society urged anti-war protestors to violence. In the ensuing years, one part of the group broke off to form the Weather Underground and took matters into its own hands, bombing a number of federal buildings and attacking local police facilities and other targets to further its revolutionary vision. WFO investigated bombings at the Pentagon, the State Department, and other area locations in the early 1970s.

On January 8, 1969, tragedy struck WFO when Special Agents Edwin R. Woodriffe and Anthony Palmisano were shot and killed by escaped federal prisoner Billie Austin Bryant. The agents had just entered a Southeast Washington apartment building where Bryant was hiding when he shot the two men. Bryant had escaped the previous summer from a nearby prison, where he had been serving a long sentence for robbery and assault. Both agents died at the scene. Bryant was quickly captured, tried, and found guilty of the two murders, receiving a life sentence for each.

Special Agent Edwin R. Woodriffe

Special Agent Anthony Palmisano

In 1970, WFO became involved in a bizarre hijacking incident. While aboard a plane that was flying over New Mexico, Arthur Gates Barkley, Sr. stormed the cockpit with a pistol and straight razor and forced the pilot to fly to Dulles International Airport in Northern Virginia. He demanded a ransom of more than $100,000, but he collected the money, released no passengers, and ordered the pilot to take off once again. He then demanded a much larger sum of $100 million, but when the plane landed a second time soon after, WFO agents formed a human ladder, boarded the plane, and shot and subdued Gates. Although Gates shot the pilot of the plane in the stomach, no others were harmed.

In the early 1970s, WFO played a major role in investigating perhaps the most serious political crime in our nation’s history—Watergate. In June 1972, five men were arrested for breaking into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters with wiretapping and other surveillance devices. Investigation by WFO agents quickly raised the specter of high-level involvement. Despite a cover-up by President Nixon and some of his closest advisors, WFO and FBI offices nationwide worked diligently to uncover the crimes committed by the White House. In the end, President Nixon resigned and several of his advisors were sent to jail.

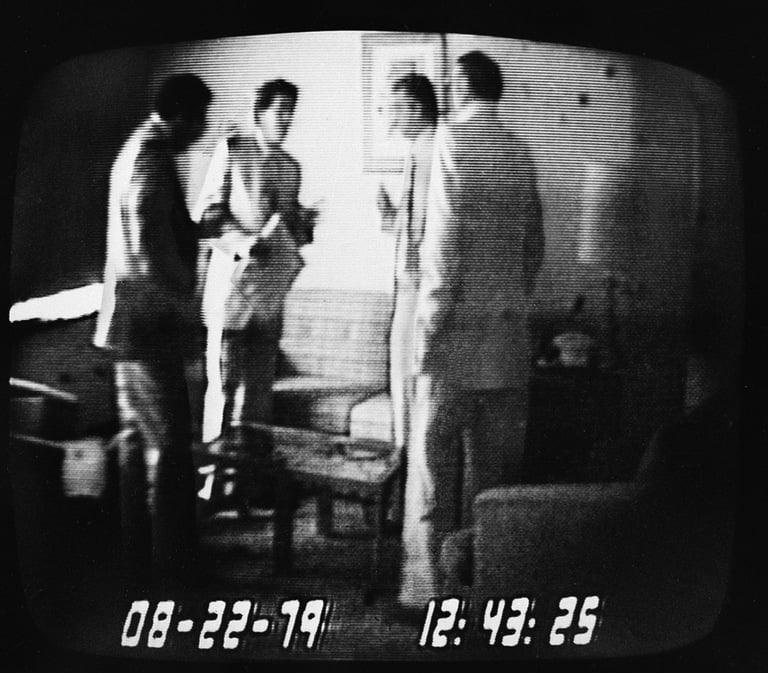

During the 1970s, the Bureau began to use undercover operations as a regular investigative tool. WFO applied this tool to great effect in a case in the mid-1970s. Working hand-in-hand with the Washington Metropolitan Police Department, WFO agents created a company named PFF, Inc.—which secretly stood for Police-FBI-Fence, Incognito—and opened its warehouse for business in Northeast Washington in October 1975. A second company—the H & H Trucking Service, a subsidiary of GYA, Inc. (Got You Again)—was opened soon after. Both companies appeared to be legitimate businesses, but actually were run by undercover agents and detectives who bought a variety of stolen goods from a wide range of D.C. thieves—taping and documenting all of the transactions and gathering evidence of crimes and criminals. Eventually, law enforcement threw a “party,” inviting all of their “clients” and promptly arresting them as they arrived for the festivities.

Early Washington field office

An FBI agent (left, with back to camera) discusses a payoff with a congressman (next to him) and others during the undercover ABSCAM sting.

WFO played a key role in another famous undercover operation that began in New York in 1978. New York agents set up a bogus company called Abdul Enterprises, said to be owned by a wealthy Arab sheik who wished to invest oil money in valuable artwork . This successful investigation, known as ABSCAM, soon led to corrupt politicians in southern New Jersey and later Washington, D.C, where WFO provided key support as one corrupt politician led to others. When the dust settled, one senator, six congressmen, and more than a dozen other criminals and officials had been arrested and found guilty.

International terrorism was also a concern during this time period. For example, the office investigated the political assassination of Orlando Letelier and the seizure of several offices of Jewish organizations by a group known as the Hanafi Muslims in the mid-1970s.

1980s and 1990s

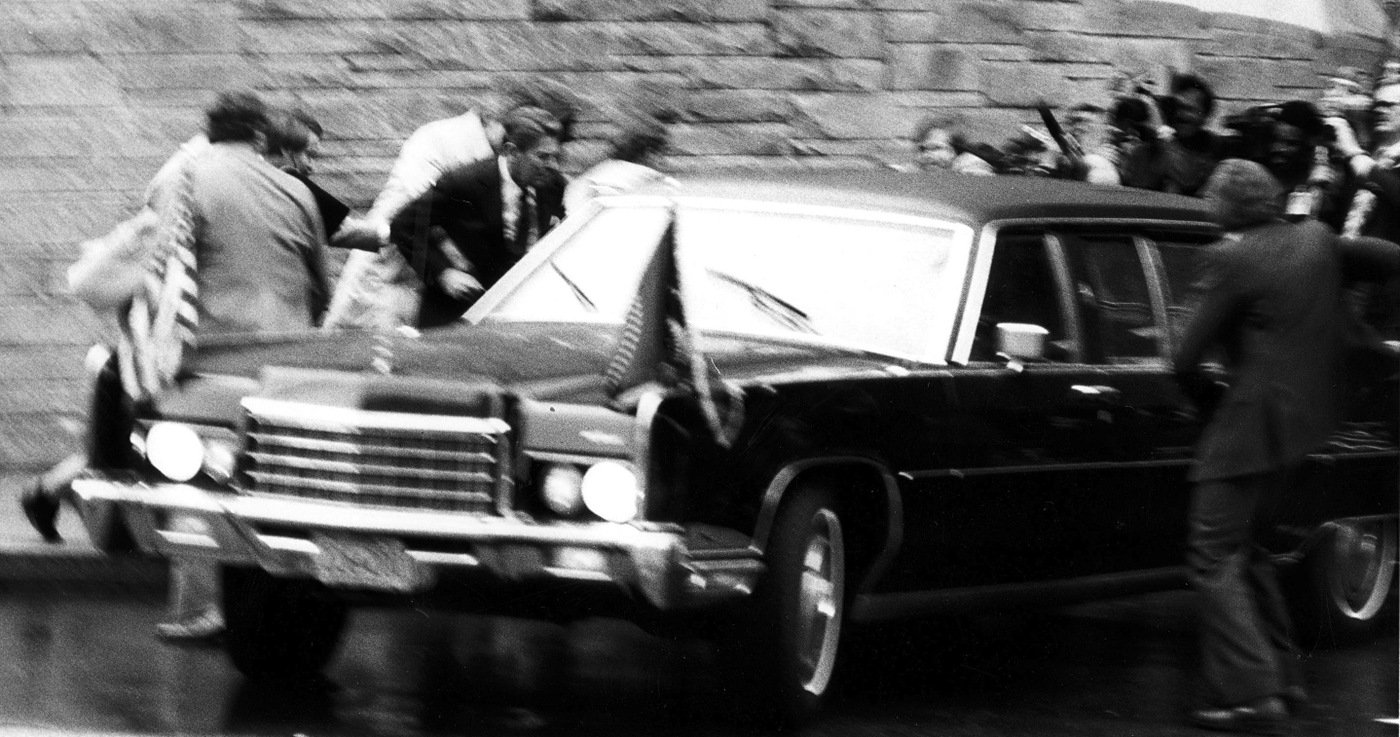

WFO’S high-profile work continued in full force in the latter decades of the 20th century. When John Hinckley attempted to murder President Reagan at a D.C. hotel in 1981, it was WFO that diligently went over his trail and all evidence to ensure that he was not part of a wider conspiracy. The office also served as the home of the FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team, a special elite counterterrorism group created in preparation for the 1984 Summer Olympics (the team later became part of FBI Headquarters). And political corruption remained a key concern as WFO agents investigated everything from the Iran-Contra scandal to Defense Department procurement fraud in the Illwind case.

President Reagan assassination attempt by John Hinckley

With the crumbling of the East Bloc in the late 1980s and the fall of the Soviet Union soon afterwards, national priorities began to shift. In the D.C. metropolitan area and nationwide, violent crime became the FBI’s top priority, and we joined with a range of law enforcement partners in standing up Safe Streets Task Forces across the country to address the problem. In D.C., the Washington Safe Streets Task Force brought WFO personnel together with federal and local law enforcement partners and prosecutors to tackle the growing violence on the streets.

Such cooperative efforts were successful. In the early 1990s, for instance, WFO joined with the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Washington Metropolitan Police Department, and others in shutting down the criminal empire of drug lord Rayful Edmunds. Around the same time, another FBI sting led to the arrest of D.C. Mayor Marion Barry on drug charges.

The dangers of violence were real, even for law enforcement. On November 22, 1994, Special Agents Martha Dixon Martinez and Michael John Miller, as well as a D.C. police detective, were shot and killed inside the District’s police headquarters building. The killer was a suspect in a triple homicide when he entered the police building and began firing on the unsuspecting officers. The murderer died in the return fire by police. Another WFO agent—William Christian, Jr.—lost his life less than a year later; he was conducting surveillance in his car when he was shot by a murder suspect.

Special Agent Martha Dixon Martinez

Special Agent Michael John Miller

Special Agent William Christian, Jr.

The end of the Cold War did not diminish the importance of WFO’s national security responsibilities. In the 1990s and into the early 21st century, the office helped identify and arrest a number of high-placed moles who had worked for the USSR and its successor intelligence agencies, including Aldrich Ames and James Nicholson of the CIA and Earl Pitts and Robert Hanssen of the FBI. Agents from WFO also continued to pursue terrorists and others who used violence to make political points. In one case, agents tracked Mir Aimal Kansi to Pakistan, where they worked with Pakistani officials to secure his arrest and extradition to the U.S. for murdering CIA personnel outside of its Virginia offices.

Meanwhile, WFO continued to make progress on other fronts. In 1997, the Washington Field Office moved to its current location—a modern, standalone facility at 601 4th Street—after spending 17 years at “Buzzard’s Point” in the Harkins building at 1900 Half Street in Southwest D.C. In 1998, the office also established its first Citizens’ Academy, hosting 19 area leaders in its initial class.

Post-9/11

When terror struck on 9/11, WFO responded immediately. It managed the site of the crash at the Pentagon, gathering evidence and working closely with the FBI Laboratory to identify victims, including those aboard American Airlines Flight 77 and those within the Pentagon.

Immediately, the work of the Bureau—and WFO—shifted to preventing terrorist attacks as its overriding priority. Ever since, WFO has not only worked to protect the nation’s capital but has also sent scores of its agents, analysts, linguists, and other experts around the world in support of terrorist investigations and to gather intelligence for the FBI and the U.S. government as a whole. For example, WFO Special Agent George Piro debriefed Saddam Hussein following his detention by the American military in Iraq, uncovering vital intelligence along the way. WFO agents and personnel also played important roles in special events, including the Presidential Inauguration of Barack Obama in January 2009.

Washington Field Office Evidence Response Team members at the Pentagon shortly after the 9/11 attack

FBI agent works on laptop in vehicle during 2009 inauguration

Meanwhile, WFO continues to launch major criminal investigations that are dismantling gangs and gang leaders, taking down corrupt figures like Jack Abramoff, exposing white-collar frauds of all kinds, and tracking down Internet predators and cyber thieves.

To support its national security and criminal responsibilities, WFO has worked to build stronger relationships within the community. In 2005, the office helped create the Arab, Muslim, and Sikh Advisory Council, which discusses issues and seeks solutions. In 2008, WFO also opened the Northern Virginia Resident Agency in Manassas, Virginia, giving it a second modern operational facility.

With more than 830 special agents and more than 850 professional staff, the Washington Field Office remains at the forefront of the FBI’s efforts to protect the people and defend the nation.