FBI Denver History

Early 1900s

The Bureau has had an office in Denver since its earliest days. In 1911, Roy O. Samson was serving as special agent in charge. Like most offices in the early years, the division investigated federal crimes such as peonage (forced labor) and the theft of interstate shipments. By 1922, Samuel J. McAfee was special agent in charge. The office closed temporarily in 1931, but it reopened in 1935 under the leadership of R.D. Brown.

1940s and 1950s

By 1939, 11 agents were assigned to Denver, handling 289 pending investigations in the states of Colorado and Wyoming. Two years after that, the caseload had almost quadrupled. National security had become the top priority as Europe went to war and America prepared for the worst.

During World War II and the years following, the Denver office investigated bank robberies, national security matters, and Selective Service Act violations. The division also handled several cases involving aircraft, including search-and-rescues in the mountainous terrain, air piracy, and sabotage.

Early Denver field office

Its biggest aircraft sabotage case came in 1955. On November 1 of that year, an explosion blew a large hole in the side of United Airlines Flight 629, causing it to crash at Longmont, Colorado. All 44 passengers and crew were killed. Denver personnel and other Bureau people responded immediately to investigate the crash and to help identify its victims. They painstakingly pieced together the plane and discovered the remnants of a suitcase bomb. Jack Gilbert Graham immediately emerged as a suspect. He had taken out four insurance policies on his mother—one of the plane’s passengers—before packing her suitcase with dynamite and driving her to the airport. Graham was convicted of murder and sentenced to death.

Wreckage of United Airlines Flight 629

FBI Denver also played a key role in the early days of the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives program. The Bureau launched the initiative in 1950, and the next year, Denver agents captured Raymond Edward Young in the city, just four days after the Bureau had named him to the top ten list. Young was wanted for assaulting and shooting a police officer.

Denver agents captured three more Ten Most Wanted fugitives during the 1950s. In 1952, a citizen listening to a criminal’s physical description on the True Detective Mysteries radio program provided a tip to authorities. Based on that lead, Denver agents and local law enforcement captured Harry H. Burton in Cody, Wyoming. Burton was accused of killing a man during an armed robbery. Daniel Everhart, who had committed several armed robberies and burglaries, was picked up in Denver in 1955. And four years later, agents nabbed cowboy Richard Hunt at his Thermopolis, Wyoming ranch. Hunt had kidnapped, shot, and wounded an Oregon police officer.

1960s and 1970s

During the 1960s, FBI Denver investigated more interstate shipments thefts, automobile theft rings, domestic security/domestic terrorism matters, and deserter cases.

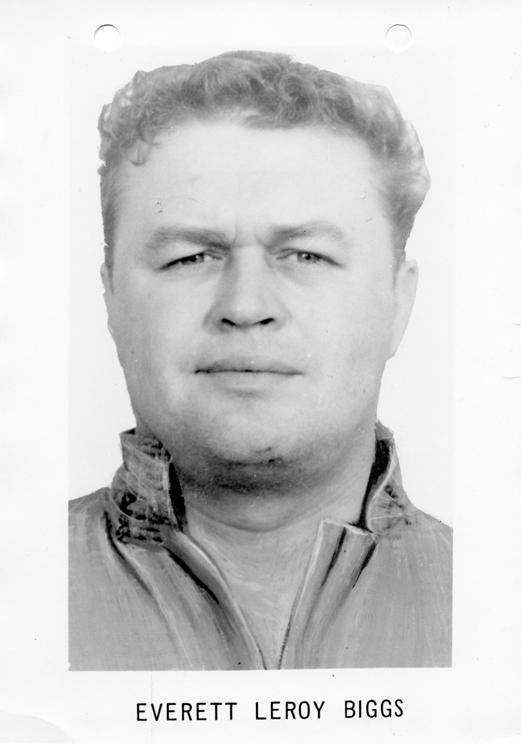

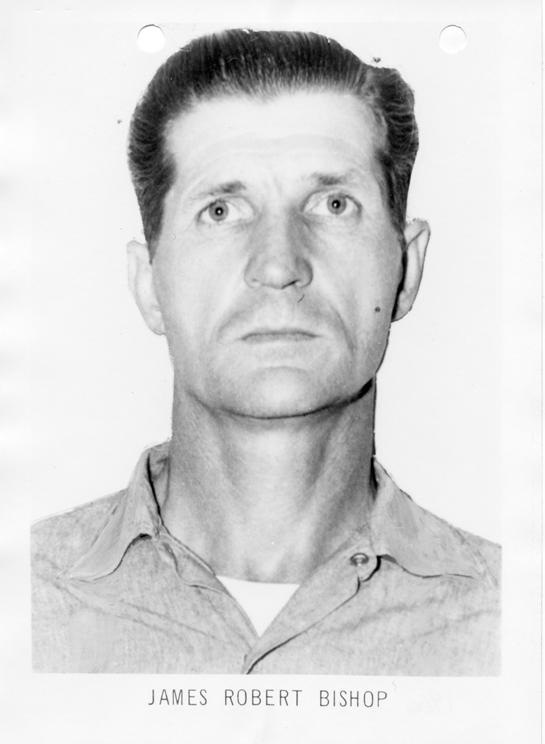

The division also continued to handle bank robberies and catch fugitives. Ernest Tait, named to the Ten Most Wanted fugitives list after skipping town on burglary charges; was nabbed by agents in Denver in 1960. Only three days after being named to this list in 1961, a citizen tip led agents to capture Chester Anderson McGonigal in Denver. In a murder attempt at a bar, McGonigal had slit his wife’s throat and then fled. During 1966, two more Top Tenners were arrested: Everett Biggs—a serial armed bank robber—in Broomfield, Colorado; and James Robert Bishop—who fled after a robbery arrest—in Aspen.

Chester Anderson McGonigal

Everett Leroy Biggs

James Robert Bishop

The division pursued other violent criminals. In 1960, it helped identify the man who kidnapped and murdered Adolph Coors, III, heir to the Coors Brewing Company fortune. During a nationwide search, Denver agents also caught Francis Alexander Akers and Bradley Hinckley, two dangerous Pagan motorcycle gang members in early 1970. They were among the 10 gang members who had been indicted in Virginia for murder, abduction, and conspiracy related to the torture murders of two Satan’s Saints gang members. Denver received a lead that the two fugitive Pagans, using aliases, had rented a car with Colorado license plates. Agents tracked them to a Boulder motel where they were sleeping. The agents were especially wary, as Akers was known to keep hand grenades on his person and in his car and to rig his automobile with dynamite to explode if apprehended. When arrested, Akers had a knife with a four-inch blade beside his bed, and Hinckley had a loaded .38 revolver under his pillow. By the time of their capture, agents in other offices had caught all but one of the 10 fugitives.

The Denver Division also investigated a Colorado Mafia family during the 1970s. The family’s “boss,” Eugene Smaldone, was convicted and imprisoned in 1974 following FBI investigation. The next year, acting boss Clarence Smaldone, other family members, and various associates were convicted of interstate gambling charges in related investigations. The subsequent prosecutions were successful due to the quality of the division’s work breaking the illegal multi-million dollar sports bookmaking enterprise.

FBI Denver also faced challenges in dealing with the threat from violent revolutionaries of the day. The office teamed with other divisions and law enforcement during 1970s to investigate the criminal acts of a group known as the American Indian Movement (AIM). In 1973, for example, five sticks of dynamite were sent to AIM members in South Dakota; Denver agents helped identify the procurers and transporters of the explosives and recover the explosives. A couple weeks later, 200 AIM members seized a church and trading post in Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Denver personnel assisted other divisions in bringing a successful closure to their 71-day siege.

Lone criminals could be serious threats, too. In 1976, a man named Roger Lyle Lentz was fired from his job. He began drinking heavily and argued violently with his wife. Armed with a shotgun and revolver, Lentz hijacked a small aircraft in Nebraska and seized two hostages. Lentz’ brother characterized him as suicidal and homicidal. Lentz commandeered the plane to Stapleton International Airport in Denver and demanded to be flown to Mexico. He shot at Denver agents several times from the plane. When attempted negotiations broke down, Denver agents—working with the Colorado governor and the Federal Aviation Administration—got access to the transfer aircraft that Lentz demanded. They hid on board and waited as Lentz arrived, holding a gun to a hostage’s head. One Denver agent suddenly yelled, “Do you want us to close the cabin door?” surprising the gunman who turned his head, diverting his attention from his hostage and giving agents a chance to shoot him. Lentz was killed, and the hostages were unharmed.

Major theft was another concern for the division, as demonstrated in two major cases in the late 1970s. In Operation Den Mother, 25 federal and local arrests were made and $300,000 was recovered. During the case, an active duty army captain at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal sold undercover agents 10 cases of plastic explosives and government checks totaling $75,000. In Operation Longbranch, Denver agents joined Lakewood County Police Department officers and Department of Public Safety officials in making 63 arrests and recovering almost $1.2 million in property. As Longbranch wound down in 1978, 25 federal and local subjects were convicted, and 65 more were waiting trial.

The mineral wealth of the region led to other investigations involving oil industries in Colorado and Wyoming. In 1977, the oil refinery in Casper, Wyoming received a demand for $1 million. The extortionists provided complicated instructions that made investigating the case challenging—included posting a newspaper ad, leaving a suitcase payoff following a bus trip, and introducing a last-minute innocent third party courier. Denver’s round-the-clock surveillance revealed the culprits—Wayne Warren Kruckenberg and David O’Neal, who were arrested on extortion and Hobbs Act violations.

1980s and 1990s

In 1981, the Denver Division began hunting for Top Ten Most Wanted fugitive John William Sherman soon after he escaped from prison, where he was serving a 30-year sentence for revolutionary terrorism and bank robbery. More than 40 Denver personnel set up physical and technical surveillance at several residences to outsmart Sherman. The investigation narrowed down his possible location, but he was known to possess materials to make false identities and was extremely security conscious. Denver’s round-the-clock surveillance ultimately paid off when Sherman was apprehended without incident in Golden, Colorado.

Later that decade, Denver investigated the notorious “Capital Hill rapist” suspected of attacking more than 30 women in capital hill region of Denver. The exhaustive interviews, technical surveillance, and relentless inquiries of Denver agents led to Quintin Keith Wortham being identified as the rapist and being captured in Georgia. Wortham was later linked to rapes in Louisiana, Georgia, New York, and Connecticut. In 1988, he received a 376-year sentence on 14 counts of rape and burglary.

FBI Denver also saw increased white-collar crime in the 1980s, reflected in its investigation of international con men Barry Krown and Anthony Cavanaugh. This complicated case involved worthless offshore banks accounts, certificates of deposit, and cashiers checks. Two Denver banks were victimized, with losses estimated at over $500,000. To make its case, Denver agents prepared over 500 exhibits. They noted that unlike earlier, less sophisticated crimes, the preparation and presentation of a white-collar crime case was sometimes more difficult than its evidence gathering stage.

In 1981, a Denver agent noticed a Wall Street Journal ad and suspected fraud. Partnering with the IRS and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, FBI Denver launched a case that uncovered offshore banks and shell corporations and ultimately touched every FBI field office and six overseas offices. After Trenton Harold Parker was caught and pled guilty, the court seized cash and precious metal assets more $6.4 million. Following investors’ disclosures, the IRS disallowed over $75 million in tax deductions, netting a return to the U.S. government of about $80 million.

Rocky Flats nuclear weapons plant

Begun in the late 1980s in concert with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the division’s PENNCON investigation was the FBI’s first undercover operation to successfully investigate the illegal manipulation of low-value securities called penny stocks. Worthless stock was being overvalued on the statements of financial institutions, insurance companies, and pension funds. As the case was wrapping up in 1991, three individuals had been convicted and 28 had been indicted by federal grand jury. Five subjects were presidents or principals of securities firms. As a result of the case, the National Association of Securities Dealers began to electronically monitor and provide price quotes for penny stocks on a real-time basis, and the Securities and Exchange Commission limited broker-dealers from selling penny stocks to innocent investors using high-pressure phone sales techniques.

The Denver Division was also responsible for the Bureau’s first major environmental crimes investigation. In the late 1980s, whistle-blowers at the Rocky Flats nuclear weapons production facility brought tales of illegal dumping, unsafe practices, and other dangers and crimes to the attention of the Environmental Protection Agency and the FBI. Working together, the agencies were able to show serious violations of the Conservation and Recovery Act and the Clean Water Act. In the end, the company that ran the facility admitted wrongdoing and paid a significant fine.

The division also responded to increased drug trafficking in the 1990s—frequently with links to Mexican gangs and other organized criminal organizations. Denver investigated major drug trafficking subjects including Rosario Portillo-Rodriguez, Diane and Calvin Bennet, Alfredo Sanchez, and Theodore Reed Campbell.

In 1994, the president of the software firm Ellery Systems reported to FBI Denver the theft of source code that had been developed for the emerging “information superhighway.” This led to an early economic espionage case. An Ellery programmer who was a Chinese national had transferred the code to another Chinese national, quit his job, and tried to sell the code to a company called Beijing Machinery for $500,000. He was arrested, confessed, and was indicted. Prosecutors declined the case, however, because evidence didn’t support wire fraud—the only possible violation at that time. The case was considered key to the passage of the Economic Espionage Act of 1996.

Post-9/11

The events of 9/11 led to a stronger focus—in Denver and nationwide—on preventing and solving acts of terror and improving intelligence capabilities. This led to far-reaching changes in the FBI. Denver’s Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF)—officially created in 1997 to leverage the resources and skills of the FBI and many partner agencies—was strengthened in the days following the attacks. A Denver Field Intelligence Group was also established in 2003 to proactively gather information on key security and criminal threats.

These new and strengthened capabilities were instrumental in the investigation of Najibullah Zazi, a citizen of Afghanistan with permanent resident status who resided in Aurora, Colorado. In early September 2009, Zazi drove from Colorado to New York City, planning to detonate explosives on the New York subway during rush hour. An encounter with U.S. authorities caused him to return to Colorado, where he was arrested. On February 22, 2010, Zazi pled guilty to conspiring to use weapons of mass destruction, to conspiring to commit murder in a foreign country, and to providing material support to a terrorist organization.

The division also continued to handle its many criminal investigative responsibilities. In July 2008, for example, 27 members of the Asian Pride street gang were indicted on 109 counts by a federal grand jury in Denver. Charges included conspiracy, distribution, and possession with intent to distribute Ecstasy. More than 10,000 tablets were seized, culminating in a two-and-a-half year investigation by the FBI and other members of the Metro Gang Task Force. Special Agent in Charge James Davis called the task force one of the most successful of its kind in the country.

In this post-9/11 world, the Denver Division continues to tackle a wide variety of national security threats and federal crimes—from terrorism to cyber attacks, from healthcare and investment fraud to illegal gambling enterprises, child pornography, and gang activity. With new tools and capabilities, FBI Denver is committed to continuing its work to defend the people and protect the nation.

An FBI agent outside the apartment of Najibullah Zazi in Aurora, Colorado. AP Photo.