FBI Chicago History

Early 1900s

From the earliest days of the Bureau, it was clear that agents were permanently needed in two cities—New York and Chicago. By July 21, 1908, several days before the FBI’s official birthday, the Department of Justice had assigned four special agents to Chicago. They included Special Agent in Charge M. Eberstein and Special Agents Dolan, Hobbs, and Edward J. Brennan (later the special agent in charge).

The new office faced many difficulties. Special Agent in Charge Eberstein fell seriously ill, as did Agent Dolan. Another agent—hired soon after the original four—had to be dismissed for failing to serve a subpoena and for poor performance in other matters. These setbacks did not last long, and the Chicago Division quickly began to carry out its investigative mission.

The office grew slowly in its early days. In 1911, Charles De Woody was special agent in charge, managing six agents and two stenographers. Several special examiners and two or three accountants also served in the division, pursuing fraud, white-collar crime, and other federal violations. Five antitrust agents also operated out of Chicago, but they answered to Bureau Headquarters for their assignments.

The range of investigations conducted by the new office was wide—from interstate prostitution and the activities of early organized crime groups like the “Black Hand” to the violent crimes of a labor union known as the International Workers of the World.

Early Chicago Field Office

Issues of food safety and corruption in the large Chicago meat processing industry were of concern, too. Upton Sinclair’s exposé, The Jungle, led to new federal laws and regulations. In U.S. v. Nelson, Morris, and Co., for instance, Chicago agents served subpoenas on witnesses, shadowed packing company employees to gather evidence, and otherwise supported the efforts of a federal grand jury to unearth the illegal rebating schemes of meat packing companies.

As World War I raged in Europe, national security matters became increasingly important to the Chicago Division. In early 1917, a Chicago businessman approached Special Agent in Charge Hinton Clabaugh and proposed the creation of a citizen’s auxiliary to the Bureau to assist with national security-related investigations. The attorney general approved of the idea, and the American Protective League was born. The group expanded quickly to other cities, providing additional manpower for anti-subversion cases, draft dodger raids, and other investigative matters. Too often, though, the group acted as a law enforcement organization, overstepping its bounds and intruding on the rights and liberties of the American people. With the war ended, the Justice Department dissolved the league during the winter of 1918/1919.

1920 and 1930s

FBI Agent Edwin C. Shanahan

In 1920, the Bureau reorganized its field structure, creating eight regional offices to oversee much of the work of agency. The Chicago Division was one of the eight offices, led by James P. Rooney. This reorganization was short lived, and Headquarters soon resumed its oversight role.

The division operated continuously during this time, tackling some of the Bureau’s most important cases. It also experienced the first death of a Bureau agent in the line of duty. On October 11, 1925, Chicago Special Agent Edwin C. Shanahan and members of the Chicago Police Department staked out a garage where an automobile thief named Martin James Durkin was expected to steal a car. Durkin had a lengthy record and had previously shot and wounded three policemen in Chicago and one officer in California. Shanahan was unarmed and tried to approach Durkin under a ruse, but the thief fired, fatally wounding the agent. Durkin fled before the Chicago officers could catch him. A nationwide manhunt ensued, with Bureau agents tracking Durkin across the western United States. He was finally captured on January 20, 1926 near St. Louis, Missouri. At that time, killing a federal agent was not a federal crime. Nonetheless, Durkin was tried and convicted on various state and federal charges and sent to jail until 1954.

The Chicago Division pursued other notorious criminals of the day, including legendary gangster Al Capone, but it was the office’s role in hunting down John Dillinger and his band of criminals that helped raise the stature of both the Chicago FBI and the Bureau as a whole.

The Bureau joined the chase in early March 1934, when Dillinger broke out of a jail in Crown Point, Indiana. He committed a federal crime by stealing a sheriff’s car and driving it over the state line between Indiana and Ohio. At the time, Crown Point was part of the jurisdiction of the Chicago Division. Led by Special Agent in Charge Melvin Purvis, Chicago agents became involved in key parts of the case and supplied important manpower to Inspector Samuel Cowley’s flying squad, which was overseeing the national investigation. On July 22, 1934, an informant—the notorious “lady in red” (her dress was actually orange)—tipped off Purvis that Dillinger would be at the movies in downtown Chicago that night. Staking out both possible theaters, agents from Chicago and the flying squad killed Dillinger outside the Biograph when he tried to flee and reached for his weapon.

Following up on this success, Chicago agents also helped track down “Pretty Boy” Floyd, “Baby Face” Nelson, and many other dangerous criminals, effectively ending the gangster era. The costs were high, however. In April 1934, Chicago Special Agent W. Carter Baum was gunned down by Nelson near a Wisconsin resort. Later that year, Baby Face killed two more agents—Sam Cowley and Herman F. Hollis—during a gun battle near Barrington, Illinois. The agents mortally wounded Nelson in the process.

Special Agent W. Carter Baum

Special Agent Herman E. Hollis

Special Agent Samuel P. Cowley

The major cases continued. On September 25, 1937, 72-year-old Chicago businessman Charles S. Ross—president of the Carrington Greeting Card Company—was kidnapped at gunpoint while driving near Franklin Park, Illinois. Despite being paid a ransom of $50,000, the kidnappers murdered Ross. His body was found four months later in a shallow grave near Spooner, Wisconsin, along with the body of one of his abductors. John Henry Seadlund—the mastermind of the plot—was arrested by FBI agents at Santa Anita race track in Los Angeles on January 14, 1938 following an extensive nationwide manhunt. He was returned to Chicago, where he was tried and convicted of the kidnapping and murder of Ross.

1940s and 1950s

The focus of FBI Chicago—along with the rest of the Bureau—soon turned to national security concerns as Europe moved closer to war and World War II eventually unfolded. The Chicago Division increased its national security work and began providing plant security advice to local manufacturers involved in war-related production.

The division was also involved in one of the FBI’s most famous World War II spy cases—the capture of eight Nazi saboteurs on U.S. soil. Building on information from George Dasch—one of the German operatives who had turned himself in—Chicago agents tracked down and arrested Herman Neubauer and Herbert Haupt on June 27. The other saboteurs were rounded up as well.

Even during the war, violent criminals continued to plague the Chicago area. On October 9, 1942, a group of dangerous felons—including Roger “The Terrible” Touhy and Basil “The Owl” Banghart—escaped from an Illinois prison. The Bureau lacked jurisdiction at first, but later began to track the fugitives on a federal violation of failing to register under the Selective Service Act. The Chicago Division—with the oversight of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in Washington, D.C.—began to close in after running down thousands of leads. Hoover was personally involved in the capture of Touhy, Banghart, and other gang members in Chicago in December 1942.

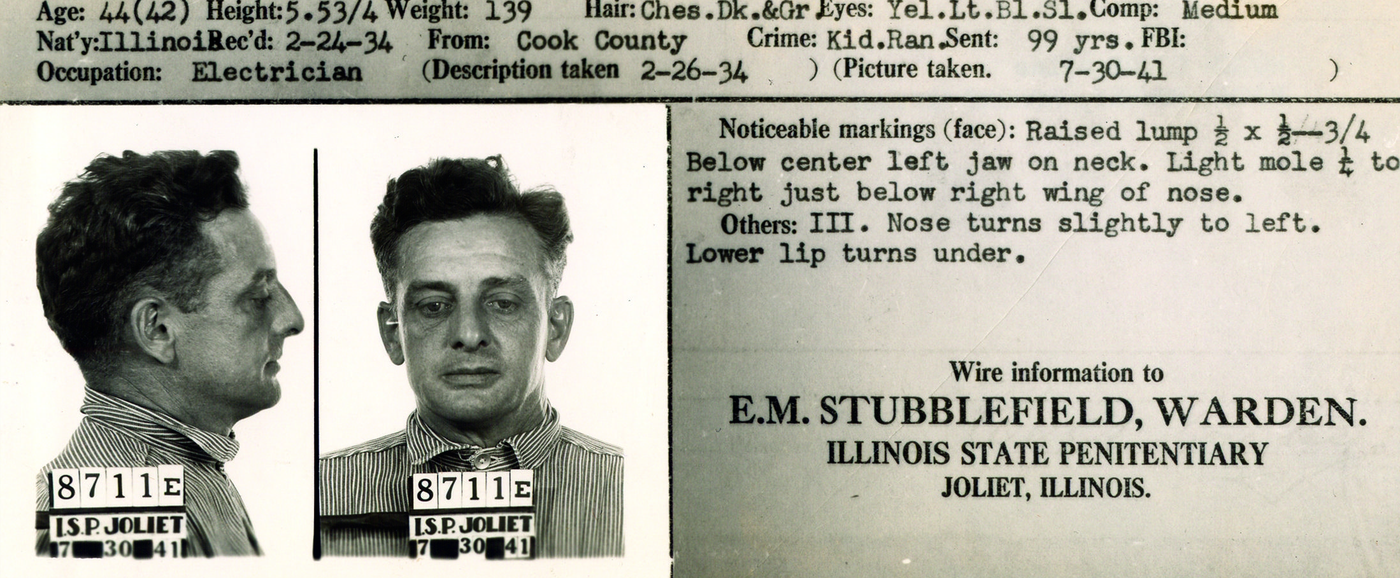

Roger "The Terrible" Touhy Mug Shot and Criminal Record

Issues of national security continued to be the Bureau’s top priority following the end of World War II, and the Chicago Division played a significant role, working to identify spies and protect national secrets and sensitive technologies developed in the area. In the late 1940s, Chicago agents recruited one of the most important FBI double agents of the time—Morris Childs. Childs was a high-ranking communist who spent decades working with his brother and his wife in cooperation with the Bureau to detail the clandestine relationship between the Communist Party of the United States and the Soviet Union. He has also been credited with providing significant foreign intelligence information, according to author John Barron in the book Operation Solo.

In the early 1950s, working from then top secret signals intelligence, the Chicago Division investigated Ted Hall—a young, brilliant physicist who had given atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. Because the highly classified intelligence on Hall could not be used in court, the Bureau couldn’t develop a prosecutable case against Hall. He was kept from working on other classified and sensitive projects, and he soon immigrated to England, where he taught physics until his death in 1999.

In May 1954, Chicago agents arrested a number of Puerto Rican Nationalist Party members on seditious conspiracy charges. That March, several members of the group had fired pistols from the galleries that oversee the U.S. House of Representatives in the nation’s capital. Four years earlier, other Puerto Rican nationalists had attempted to assassinate President Truman.

Throughout the 1950s, the division also handled many bank robbery, white-collar crime, and organized crime investigations. In the midst of these many cases, Chicago lost three more agents when their car crashed as they returned from a weekend hunting trip in November 1953. Two others were wounded—one seriously—in the accident.

1960s and 1970s

On August 27, 1964, the Chicago Division moved into new space located in the just completed E.M. Dirksen Federal Building and Courthouse. Located at 219 South Dearborn Street in Chicago’s “Loop,” the Chicago FBI occupied the entire ninth floor of the building. Marlin W. Johnson was the special agent in charge, and the office included 281 special agents and 185 support employees. The Dirksen building remained the home of the division for the next 42 years. During that time, the office expanded to occupy the entire eighth and 10th floors and part of the 11th floor.

In October 1969, violent members of a radical group known as the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) bombed a Chicago police memorial and fomented the “Days of Rage” riot in Chicago. An offshoot of SDS called the Weathermen—later the Weather Underground Organization—which evolved into a domestic terrorist group that used bombings, robberies, arson, and other illegal acts to further its radical political agenda. Chicago agents, along with other field offices across the country, thoroughly investigated this organization and its activities. In 1974, the Chicago Division produced an extensive summary of the group’s motivations and activities.

The FALN (Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación National/Armed Forces of National Liberation)—which advocated Puerto Rican Independence—was another 1970s terrorist group subject to intense investigation by the Chicago Division. In the early morning hours of October 27, 1975, bombs exploded outside three Chicago Loop office buildings, including the Sears Tower. A fourth device was found outside the Standard Oil building, but was disarmed before detonating. Almost simultaneously, five bombs exploded outside four New York banks and the U.S. Mission to the United Nations, while two devices detonated outside government buildings in Washington, D.C. The bombings were part of a series of such incidents in Chicago and other cities between 1975 and March 1980. A total of 19 bombings, six incendiary attacks, and two armed takeovers of offices and businesses occurred in the Chicago area alone during this period. The case was broken by the Chicago Division when a housewife called to report a suspicious sight—a group of smokers, all dressed in jogging outfits, standing near a panel van.

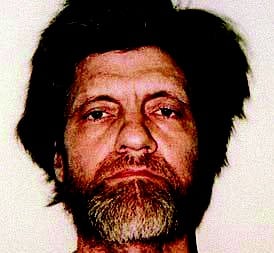

Theodore Kaczynski

In the late 1970s, the division opened what ended up being the FBI’s longest-running domestic terrorism investigation. On May 28, 1978, a bomb exploded at the University of Illinois at Chicago, injuring one individual. In 1979, an FBI-led task force that included the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service was formed to investigate the “UNABOM” case—code-named for the UNiversity and Airline BOMbing targets involved. Sixteen more bombings took place over the next 17 years, killing three and injuring more than 20 people. FBI Chicago, along with nearly all of the FBI’s 56 field offices, pursued this terrorist throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s. After an extensive investigation—and a tip from the bomber’s brother—the FBI arrested Theodore Kaczynski in April 1996. Kaczynski ultimately pled guilty and was sentenced to life in prison for his crimes.

The division also investigated major thefts during the 1970s. On October 21, 1974, for instance, Purolator Armored Express Company officials and firefighters responded to a smoke alarm from inside a vault. The officials discovered that more than $4 million was missing. The thieves had apparently tried to set fire to the remaining contents of the vault in an effort to conceal the theft, but the fire had burned itself out due to a lack of oxygen. Subsequent investigation by Chicago agents resulted in the arrest and conviction of seven men for the theft—the largest such crime in U.S. history at the time. Approximately $3 million of the stolen money was recovered.

1980s and 1990s

During the 1980s, the Chicago Division handled its most significant case involving tainted food and drugs. Between September 29 and 30, 1982, seven Chicago area residents ingested Tylenol capsules laced with cyanide. Within a matter of hours, all seven victims had died. The murders triggered the largest product tampering investigation in the history of law enforcement, as FBI agents and nearly 120 investigators from various state and local police agencies worked to identify the culprit(s). Although no one could be charged with the murders due to a lack of evidence, James Lewis—a 37-year-old New York man—was charged with attempting to extort $1 million dollars from Johnson & Johnson, the makers of Tylenol. Lewis was sentenced to 20 years in prison. The poisonings led to the passage of a stringent federal anti-product tampering law in 1983.

Not long after this investigation began, the division experienced a tragedy. In December 1982, four Chicago agents were killed in an airplane accident near Montgomery, Ohio. The agents—Terry Burnett Hereford, Charles L. Ellington, Robert W. Conners, and Michael James Lynch—were accompanying bank fraud suspect Carl Henry Johnson and an individual from the law firm representing him to an area where agents believed Johnson had stashed $50,000 in embezzled money. The plane—piloted by two of the agents—was apparently experiencing problems with its altitude readings and crashed on approach to Lunken Airport. No one aboard survived.

A major public corruption case—one of many handled by FBI Chicago over the years—came to fruition in March 1984, when former Deputy Traffic Court Clerk Harold Conn became the first defendant convicted in a sweeping investigation called Operation Greylord. Over the course of the undercover probe of corruption in the Cook County Circuit Court, nearly 100 people—including 13 judges and 51 attorneys—were indicted and convicted. The case unfolded when a young attorney, shocked by the extent of corruption in the county judicial system, began working with the division. The corruption was so endemic that agents had to conduct surveillance of one judge’s courtroom and obtain special court authorization to present a false case in the bugged court to develop evidence of illegal activities.

The division also continued to pursue fugitives from justice. On July 20, 1984, Chicago agents arrested FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitive Alton Coleman in Evanston, Illinois. Coleman was sought in connection with a series of murders, attempted murders, rapes, kidnappings, and auto thefts. On January 7, 1985, Coleman and his accomplice, Debra Brown, were each sentenced to 20 years in prison for the kidnapping of a Kentucky college professor. On April 30, 1985, Brown was convicted of beating to death an Ohio woman and sentenced to life in prison. On January 24, 1987, Coleman received his fourth and final death sentence for the murder of a nine-year-old girl.

On August 10, 1984, some 300 FBI and IRS agents, assisted by Cook County State’s Attorney investigators, executed 14 search warrants at suburban Chicago locations as part of Operation Safebet. The investigation targeted political corruption and the control of prostitution operations by organized crime elements throughout the Chicago metropolitan area. More than 75 individuals were eventually indicted and convicted.

Undercover investigations continued to be successful throughout the decade. On November 21, 1986, the first of two federal grand jury indictments was returned as part of Operation INCUBATOR. Over the course of the investigation, 14 local officials—including a deputy water commissioner, a Cook County clerk, a former mayoral aide, and four aldermen—were charged with accepting bribes. In August 1989, another major undercover investigation led to the arrest of 46 traders and brokers of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the Chicago Board of Trade. The indictments were the result of a two-year investigation in which four agents posed as traders to uncover fraud and other crimes.

The targeting of corrupt politicians and criminal businessmen continued into the 1990s. On October 19, 1990, a judge, a state senator, an alderman, and two others were charged by a federal grand jury as a result of the Chicago Division’s Operation GAMBAT. These politicians were charged with crimes relating to corruption in the Cook County Circuit Court, the Illinois Senate, and the Chicago City Council. Four of those charged were convicted; the fifth defendant died awaiting trial. In another case in the mid-1990s—Operation Silver Shovel—six Chicago aldermen and a dozen other local officials were convicted of accepting bribes.

Color of law violations—involving an abuse of trust by public officials, including law enforcement officers—are rare but important to uncover and prosecute in a democratic society. FBI Chicago has worked its fair share of such cases over the years. For example, in December 1998, Chicago police officer Joseph Miedzianowski and 14 others were charged with running a drug distribution ring operating out of northwest Chicago. Described in the press of the day as the most corrupt cop in Chicago’s history, Miedzianowski was convicted in U.S. district court in April 2001. A year earlier, another investigation into a crooked law enforcement officer led to the arrest of William A. Hanhardt, a retired chief of detectives for the Chicago Police Department. In October 2000, he and five others were charged by a federal grand jury with masterminding a nationwide jewel theft ring.

The city of Chicago has long prided its sports teams—from the Bears to the Bulls and everything in between—and the Chicago Division has handled several sports-related cases. On July 11, 1996, for example, an investigation led by the division resulted in the first indictment in Operation Foul Ball, a nationwide probe of crooked sports collectible dealers. The case found widespread creation and distribution of forged sports memorabilia—including jerseys, shoes, bats, balls, hats, and photographs—allegedly signed by famous athletes. By the end of the investigation, seven men had been found guilty of selling forged sports memorabilia. On March 26, 1998, an FBI Chicago investigation also led to the first of several indictments in a federal probe of point-shaving schemes in the football and basketball programs of Northwestern University during the 1994 and 1995 seasons. A total of 11 individuals, including eight student athletes, were charged and convicted as a result of the case.

Post-9/11

Following the events of 9/11, preventing terrorist attacks became the top priority of every FBI field office. Chicago, with its long history of tracking and stopping terrorists, quickly worked to refine its use of intelligence and to improve its counterterrorism operations. That included strengthening its Joint Terrorism Task Force, established in 1981, and creating a Field Intelligence Group to improve the collection, analysis, and dissemination of intelligence. These efforts have paid off in a number of terror-related cases. In March 2010, for example, David Coleman Headley pled guilty to his role in planning the deadly 2008 attacks in Mumbai, India.

The division continued its investigations into public corruption, fraud, and other crimes. One of the longest-running cases was Operation Safe Roads, which began in the mid-1990s when it was revealed that truck drivers were paying bribes to the Illinois state government to obtain commercial driver’s licenses. The investigation mushroomed into a far-reaching probe of “pay-to-play” politics that ultimately led to the conviction of former Illinois Governor George Ryan in 2006 on fraud and racketeering charges. Ryan’s chief of staff and nearly 70 others were also convicted in the case.

Another major investigation—dubbed Operation Family Secrets—began in 1999 and culminated in 2005 with the indictment and arrest of 14 known or suspected members of a Chicago organized crime group for 18 unsolved mob hits. A Chicago policeman and Cook County sheriff’s deputy were also charged. The defendants all either pled guilty, were convicted in court, or died prior to trial.

In December 2008, FBI agents arrested Illinois Governor Rod R. Blagojevich and his chief of staff, John Harris, on federal corruption charges. Among other things, the pair allegedly conspired to obtain personal financial benefits for Blagojevich by leveraging his sole authority to appoint a U.S. senator and to gather campaign contributions in exchange for official actions. Blagojevich was found guilty of a variety of counts in 2011 and sentenced to 14 years in prison.

Heading into its second century of service, the Chicago Division remains committed to protecting its residents and communities from a range of national security and criminal threats.