FBI Buffalo History

Early 1900s

The FBI’s first field office in Buffalo was opened prior to 1925 to handle investigations in western New York. The first special agent in charge was M.F. Blackmon.

In 1929, the division closed, in part because it had to vacate its office building. Still, the Bureau retained its presence in city, operating as a resident agency out of FBI New York. In the spring of 1934, the Buffalo Division re-opened, with J.P. McFarland at the helm. It has been in continuous operation ever since.

1940s and 1950s

During FBI Buffalo’s early years, agents investigated such crimes as bank robbery, interstate prostitution, and violations of immigrant registration. During World War II, the division handled internal security matters and a few espionage cases. It also hunted for various fugitives—including both missing criminals and deserters from the armed services.

In 1959, Buffalo agents captured the division’s first Ten Most Wanted fugitive, James Francis Jenkins. Earlier that year, Jenkins had stolen more than $17,000 from a bank. He was sent to prison and escaped by slowly digging a hole out of his cell with a screwdriver. A citizen had provided a tip about his possible whereabouts, and agents nabbed him as he finished a shower.

According to an FBI report, the Buffalo Division was staffed by 58 agents and 44 support employees and was handling 1,252 cases in 1958. Those cases included many security investigations into the underground activities of the U.S. Communist Party, as well a major jewel theft and a fraudulent check ring, each with losses exceeding $100,000. The office was also very busy with the sensational bank robbery trial of Frank Richard Coppola and searching for Frank Wetzel—wanted for murdering two North Carolina patrolmen.

1960s and 1970s

Throughout its history, the Buffalo Division has investigated many bank robbers. Two of the most notorious were Albert Nussbaum and Bobby Wilcoxson, who conducted their first robbery in Buffalo and began accumulating a large weapons cache nearby. The pair was named to the Top Ten list in 1961 after murdering a bank guard and wounding another officer while robbing a bank. The next year, FBI Buffalo learned where Nussbaum was hiding in the city and descended on the location. Nussbaum fled before they could arrive. Following a wild car chase, Assistant Special Agent in Charge Karl Brouse blocked Nussbaum’s car, and Special Agent in Charge William Alexander arrested him. Days later, Wilcoxson was apprehended in Maryland. The two pled guilty and were sentenced to life in prison.

During this time, the division also worked a significant number of interstate car thefts, kidnappings, and civil rights violations, but it was organized crime that occupied much of the office’s time. After learning that eight area residents had attended the infamous meeting of high-ranking mobsters in Apalachin, New York in 1957, Buffalo agents began watching and investigating these and other individuals.

Although the Mafia was frequently linked to gangland murders and other violence, few of these offenses were federal violations at the time. Still, agents were able to pursue these mobsters for many other crimes, such as gambling, racketeering, extortion, burglary, and income tax evasion. Once arrested, hoodlums sometimes “ratted out” other associates, and agents gained valuable intelligence. Major legislation in the late 1960s and early 1970s gave the FBI more tools to combat organized crime, including the ability to use court-approved wiretaps and to strategically target the leadership of criminal enterprises. This helped produce more evidence and intelligence on mob activities and more successful cases in Buffalo and around the nation.

The Buffalo Division’s successes against organized crime continued to mount. Agents broke up a Mafia-run burglary ring, recovering $100,000 in furs and seizing $4 million in assets for unpaid taxes. They also arrested Salvatore Pieri for interstate jewel theft and later investigated him for jury tampering in the trial arising from his case. In the 1970s, Buffalo investigators arrested Magaddino boss Joseph Todaro; Buffalino boss Russell Buffalino; racketeer Frank Valenti; and Benjamin Nicolleti, Jr., who controlled Niagara gambling operations. Agents also coordinated raids with local authorities, arresting Angelo Massaro for bookmaking and John Sacco on murder charges—in the process thwarting a million-dollar burglary Sacco was planning.

In 1972, agents disrupted three potentially dangerous plots involving aircraft. In one case, an anonymous caller threatened to blow up a plane at Buffalo International Airport; in a separate incident, someone threatened to shoot out the tires of arriving/departing aircraft at the Monroe County Airport. Through quick thinking and brave action, Buffalo agents nabbed both culprits when they tried to retrieve their “payoffs.” The third case involved a distraught man who critically injured his wife and her paramour with a knife and boarded an empty 707 at Buffalo International Airport, demanding a pilot to help him escape. The man was holding his infant daughter and had a switchblade to her neck. Special Agent in Charge Richard H. Ash and his agents raced to the scene, where they could see the man with the infant and the knife. Agents surreptitiously boarded the plane and heard the man say that he was sorry the baby was going to have to die. Ash talked to the man for several hours, convincing him to surrender and hand his baby over unharmed.

Buffalo clerks replacing files in 1975

By 1973, FBI Buffalo’s caseload had grown to 3,125, with many investigations involving organized crime, internal security, espionage, racial matters, and Selective Service Act violations. Its staff had grown to 96 agents and 61 support professionals.

The division also worked several major insurance fraud cases during the 1970s. Noticing that a large percentage of stolen vehicles were never recovered—one estimate ran as high as 75 percent— Buffalo agents suspected fraud. They responded by launching an operation called CARNAP, setting up a garage front to buy stolen vehicles and those fraudulently reported stolen for the insurance money. After 15 months, 36 middlemen and car owners were charged, and 110 vehicles valued at $750,000 were recovered. Operations Emerald and Emerald II were launched to tackle arson insurance fraud. These cases solved over 30 major arsons involving $5 million in damages and some 50 burglaries. More than 200 subjects were indicted or convicted, $850,000 in stolen property and 125 vehicles were recovered, and 15 law enforcement officers were implicated.

1980s and 1990s

The division continued to target organized crime, resulting in major Mafia convictions. During the 1980s, Buffalo agents again arrested Benjamin Nicoletti, Jr. (who rarely served jail time), locating voluminous records concerning loan sharking, bookmaking, and infiltration of legitimate businesses. Angelo Amico—who had been extorting weekly “juice” payments from Rochester gambling operators—was also arrested for racketeering. In the 1990s, arrests included Dominick Taddeo—who was linked several murder “hits”—and Maggadino “made member” Nicholas Mauro for sports bookmaking. For more than a decade, agents had pursued powerful Maggadino consigliore Leonard Falzone, initially for bookmaking and horserace-fixing. His case grew to include his involvement in major loan-sharking activities. He and four associates were convicted in 1995.

The office also worked several espionage cases. The daughter of convicted spy John Walker resided in Buffalo and provided incriminating information about him to the division, which played an integral part in the unfolding case. FBI Buffalo also initiated the case against Niagara Falls resident and former U.S. Army cryptographer Joseph George Helmich, who was paid by the Soviets to deliver cryptographic information. Just before his 1981 arrest, Helmich moved to Florida, where the Jacksonville Division picked up his trail and the lead in the case.

Illegal drug investigations also increased during the 1980s. FBI Buffalo led a nationwide undercover case called BUSICO, short for Buffalo Sicilian Connection. The probe was directed at Italian/Sicilian drug cartels throughout the U.S. that operated independently but were often connected through various associations. The three-year investigation culminated in December 1989 with simultaneous arrests in Buffalo, Newark, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Miami, San Francisco, and Rockford, Illinois, as well as in Italy. A total of 64 individuals were charged in the U.S., and nearly $1 million was seized. The case also revealed previously unknown heroin trafficking organizations in several major U.S. cities.

In 1985, Buffalo launched GANGBUST to investigate a major bust-out scheme (in these scams, criminals use a credit line to obtain funds with no intent to repay). The investigation revealed that a highly organized group had run several bankruptcy bust-out frauds for 15 years and had not been caught because of the tedious “dot connecting” required to link the crimes. In western New York, seven major arrests were made and $500,000 was recovered; an additional 13 subjects were named and another $6 million was recovered nationwide. The scheme was halted, and in what is believed to be the first time in FBI history, individuals were charged with National Bankruptcy Act violations before declaring bankruptcy.

John Walker

During the 1980s and 1990s, the office worked several public corruption matters. In the division’s PLUMLINE (1985) and TOURWARS (1991) investigations, officials of the Niagara Frontier Transit Authority and other county and city officials were convicted of or pled guilty to bribery, payoffs, and conspiracy. A Niagara Falls sheriff also pled guilty to misusing jail funds to repay a personal debt and for other improper purposes. In a third significant corruption case, the Rochester chief of police was convicted in 1990 of embezzling more than $200,000 and living lavishly off the stolen money. While serving his prison sentence, he also pled guilty to conspiracy/civil rights violations—for looking the other way while his officers engaged in police brutality.

By 1991, the Buffalo Division considered white-collar crime and its subprogram—public corruption—its number one investigative priority. That same year, the division’s investigation of the Buffalo parks commissioner resulted in charges of fraud against the government, environmental crime, and racketeering. Park employees were required to work for friends and political backers of the commissioner and his deputy, on their personal residences, and during the workers’ breaks and personal leave time. Parks employees complied because they feared overtime denials or reassignment to the least desirable jobs.

Bank robbery and other serious violent crimes were also major concerns. Through a series of stakeouts, interviews in neighborhoods of robbed banks, and additional detective work, Buffalo agents apprehended Jonathan McKelvin and his brother-in-law, Bruce Miller. McKelvin was a former Buffalo police officer, and his knowledge of bank procedures and security consciousness made him a hard target to find. In a separate case, robber Jeffrey Adams wore an eye patch during robberies—earning him the nickname “Patches.” He manipulated his fingertips so prints could not be lifted from crime scenes, and he was known to present notes stating that he had HIV/AIDS. Catching these three men in a two-year period solved a host of cases, since McKelvin and Miller had committed nine jobs and Adams had committed more than a dozen bank and drug store robberies.

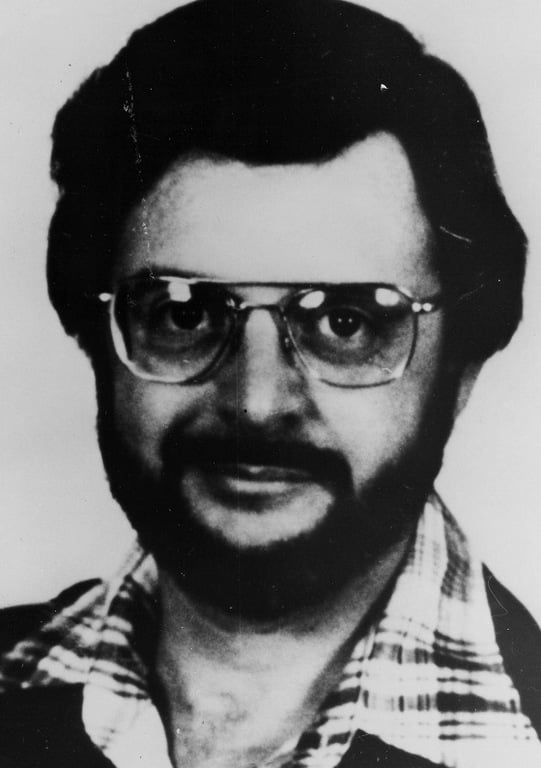

James Charles Kopp

In 1993, the Buffalo Division also investigated the fifth largest armored car robbery in U.S. history. Three Brinks employees were working at the armored car money depot in Rochester. As one Brinks guard exited the depot vault, two gunmen accosted the two remaining guards and stole $7.4 million. Three men—including a priest—quickly emerged as suspects in the investigation. They were seen meeting and carrying duffel bags and money counters. Two were convicted of the robbery, but a third suspect was acquitted.

In October 1998, Dr. Barnett Slepian—who ran a women’s clinic that provided abortion services—was shot and killed by a single sniper’s bullet at his home in Amherst, New York. An extensive investigation led by the Buffalo Division identified James Charles Kopp as the shooter. Kopp was placed on the Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list in 1999 and later tracked to France, where he was arrested in March 2001 with the help of international authorities. Kopp was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for violating weapons laws and the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act.

Post-9/11

Following the events of 9/11, preventing terrorist attacks became the top investigative priority of all Bureau field offices. As a result, the Buffalo Division stood up a Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) that year and began other reforms to increase its focus on counterterrorism.

The Buffalo JTTF’s “Lackawanna Six” investigation in 2003 dismantled an Al Qaeda terrorist cell of six U.S. citizens and residents of Lackawanna, New York. Cell members were recruited by a known Al Qaeda leader and instructed in the use of firearms and explosives at an Afghanistan terrorist training camp. They had met with and heard speeches by Usama Bin Laden, who discussed recruiting U.S. citizens for martyrdom missions and hailed bombings that targeted U.S. people and interests. The subjects pled guilty to terrorism-related charges, agreed to cooperate with the government, and were sentenced to prison terms ranging from seven to 10 years. The case helped shape the FBI’s strategy for counterterrorism investigations, and case intelligence helped deter other potential attacks.

Although national security remained its top focus, the division continued to tackle the wide ranger of federal crimes, including public corruption; cyber crime; child pornography; and bank, copyright, and mortgage fraud. In one mortgage fraud case, investigators found that Robert Amico and his two sons had conspired with loan brokers, appraisers, and buyers to submit more than 100 fraudulent mortgage applications with overstated home values. Down payments weren’t required, and buyers qualified for loans they could not afford. The fraudulently-obtained mortgage applications were valued at $58 million, and bank losses totaled $14.7 million. Robert Amico died before trial, but his sons were convicted and sentenced to nine and 17 years in prison.

Today, the Buffalo Division works to protect western New York from a broad range of national security and criminal threats, using its full suite of investigative and intelligence capabilities and working with and supporting a broad range of partners.