FBI Boston History

Early 1900s

In the summer of 1908, Attorney General Charles Bonaparte created a small force of federal detectives within the Department of Justice. Some of the earliest investigations of this new force were conducted in the Boston area. At some point during the next three years, a Bureau field office was created in Boston.

Like other Bureau offices, during these early years the Boston Division mainly investigated violations of the White Slave Traffic Act of 1910—one of several dozen federal crimes the new force was responsible for—which made the transportation of women across state lines for immoral purposes a federal crime.

With America’s entry into World War I in April 1917, the Boston office began investigating acts of espionage and sabotage as well as matters of subversion, such as interfering with the draft or encouraging disloyalty among Americans. This mandate was a challenge for the division, as Boston’s large ethnic Irish population was concerned about the U.S. allying itself with Great Britain.

Gangster Alfred Brady

1920s and 1930s

At the conclusion of World War I and into the early 1920s, the Bureau returned to its pre-war role of investigating the small number of federal crimes, including the newly passed National Motor Vehicle Theft Act (or Dyer Act) of 1920 that made it a federal offense to take a stolen vehicle across state lines.

When J. Edgar Hoover was appointed Director in 1924, the Boston Division was one of the Bureau’s larger offices, although still a small office by modern comparison. It consisted of only 17 employees under the direction of Special Agent in Charge George Shanton.

Despite the small number of special agents, the Boston Division was responsible for federal investigations in five states: Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine. This wide area of responsibility made investigations extremely difficult. In addition, there was little continuity in leadership; the special agent in charge changed nine times in eight years, a rapid turnover even at a time when Bureau leadership regularly rotated from office to office. In light of these difficulties and Director Hoover’s reorganization, the Boston Division was closed in March 1932.

The closure was short lived, as the Bureau stepped up its work in response to the rise of violent gangsters and Attorney General Homer Cummings’ resulting “war on crime.” In September 1933, the office was reopened with more than 100 employees under the leadership of Special Agent in Charge C.D. McKean. The office began investigations throughout New England, hunting for its own “public enemies.”

One of those notorious criminals was Alfred Brady, who had formed a gang in Indiana with several friends in 1935. Though small in number, Brady and his band committed some 150 robberies, at least one murder, and countless assaults. Brady even bragged that his exploits “would make Dillinger look like a piker.” Although the gang hid out in Philadelphia and other locations, Brady and his men thought Maine would be the perfect, out of the way place to buy guns and ammunition. This was a mistake. The manager of a Bangor, Maine sporting goods store became suspicious of the men and alerted authorities. On October 9, 1937, 15 FBI agents—along with Indiana and Maine State Police—arrived in town. On October 12, the gang returned to Bangor to pick up a Thompson sub-machine gun and clips they had ordered from one of the stores. Agents from the Boston Division and elsewhere, Maine State Police, and local police staked out the store. When the criminals returned to get their guns, they were surrounded. A gunfight erupted, and in less than four minutes, Brady and one of his men were dead, and a third gangster was in custody. The fight remains fixed in the memories of Bangor, Maine and the Boston Division to this day.

By the end of 1937, the Boston office had more than 125 special agents and support personnel handling nearly 700 cases.

1940s

With a second world war looming in Europe, President Franklin D. Roosevelt assigned responsibility for investigating espionage, sabotage, and other subversive activities to the FBI and other agencies in 1939. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941—and U.S. entrance into World War II—the FBI began working 24 hours a day to protect the nation from enemy threats.

In Boston, Special Agent in Charge V.W. Peterson realized the difficultly of managing this responsibility across five states, so he asked for the public’s help in reporting suspected spies and saboteurs. This request paid off in November 1944, when local citizens reported suspicious activities that helped Boston agents capture William Colepaugh and Erich Gimpel, two Nazi spies who landed at Point Hancock, Maine in a German U-Boat.

The Boston Division also focused on other wartime issues. In one fugitive case, Boston agents captured a U.S. Marine who had escaped from the New York Navy Yard’s detention facility. His name was Private Thomas Maroney, and he had been jailed for robberies in New York and Washington, D.C. Acting on a tip that Maroney was hiding in Boston, investigators turned the fugitive’s passion for ice skating against him by watching area rinks. This surveillance paid off on December 5, 1943, when agents captured Maroney putting on his skates at a Boston rink. Ironically, Alfred Brady’s love of skating had played a role in generating investigative leads as well.

1950s and 1960s

Following the end of the war, both national security and criminal work remained important.

In January 1950, the Boston Division investigated one of its biggest cases. At 7:30 p.m. on January 17, 1950, six or seven armed men wearing dark coats, dark pants, chauffeur caps, and Halloween masks held up a Brinks security firm in Boston. They placed more than $1.2 million in cash and $1.5 million in checks into two large laundry bags and made their escape. Leads were few, and the press soon called it the “crime of the century,” the “perfect crime,” or the “fabulous Brinks robbery.” Over the next six years the Boston FBI, the Massachusetts State Police, and the Boston Police worked every aspect of the case. Their diligence paid off. In August 1956, eight men—Anthony Pino, Joe McGinnis, Vincent Costa, Henry Baker, Adolph Maffie, Michael Geagan, James Faherty, and Thomas Richardson—went to trial for their roles in the Brinks robbery. All eight were found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Two other men were also found to be involved—Stanley Gusciora died of natural causes before the trial began, and Joseph O’Keefe pled guilty to armed robbery.

On March 14, 1950, the FBI began its Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list to increase law enforcement’s ability to capture dangerous fugitives. Since 1951, the Boston Division has had 21 fugitives on this list. See all of these fugitives and their fates.

By the summer of 1953, the Boston office had grown to 180 employees and occupied six floors of the Security Boston Trust Building at 100 Milk Street (also known as 10 Post Office Square). The division was handling an average of 2,840 cases per year and maintained a four state area of responsibility— Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Maine. Vermont had become the responsibility of the FBI office in Albany, New York.

The division continued to grow. By 1960, it employed more than 200 agents and support staff. The main office was now located in the Sheraton Building at 470 Atlantic Avenue in Boston; the division was averaging nearly 3000 criminal, security, and applicant investigations per year. As a result of new federal racketeering and gambling laws enacted by Congress, organized crime cases increased, but limitations in these laws made it difficult to take out the leaders of the mobster groups. The division also investigated civil rights violations and the often violent discord growing out of protests of the Vietnam War. Selective Service (draft dodging) investigations also grew in number. In October 1967 alone, the Boston Division opened 48 new Selective Service cases and received 80 additional requests for assistance on related cases from other field divisions.

The Boston office soon numbered more than 250 employees, forcing it to once again acquire new space. In June 1966, the main office moved into the entire ninth floor of the recently opened John F. Kennedy federal office building.

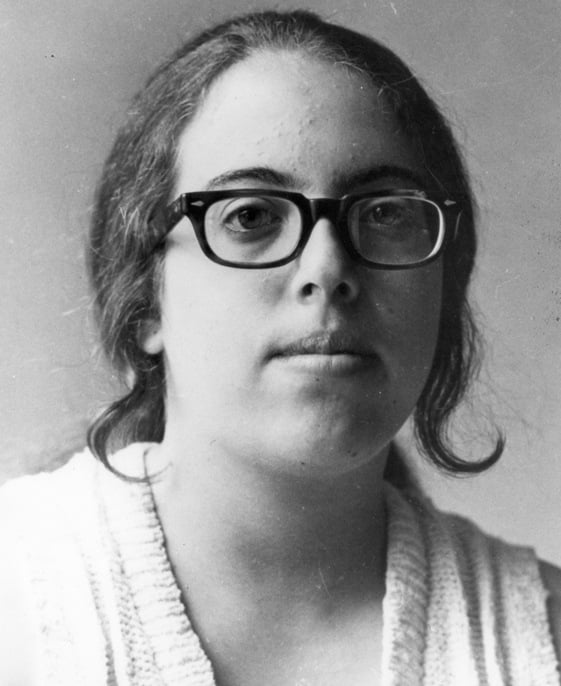

Susan Saxe

Katherine Ann Power

1970s

With the continuing opposition to the Vietnam War in the early 1970s, Boston witnessed some of its worst anti-war violence.

On September 24, 1970, two Brandeis University students—Katherine Power and Susan Saxe—joined three men in robbing the Massachusetts National Guard Armory in Newburyport and the State Street Bank in Brighton. Both robberies were committed to fund their anti-war protest activities. During the Brighton robbery, Boston Police Officer Walter Schroeder was shot and killed. The five terrorists immediately went into hiding, but the three men—William Gilday, Robert Valeri, and Stanley Bond—were quickly captured. Gilday, who had killed Officer Schroeder, received a life sentence.

The female fugitives were placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitive list, and a massive search ensued. In 1975, Saxe was captured and sentenced to five years in prison. In 1993, after 23 years as a fugitive, Katherine Power negotiated her surrender with the FBI and the Boston Police Department. She was sentenced to eight to 12 years in prison for the bank robbery and five years for the National Guard Armory crime.

Other domestic terrorist groups were also investigated during the decade. From 1976 to 1978, Boston agents pursued the Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson Unit, a terrorist group that used bombings to draw attention to its prisoner rights and anti-capitalist ideology. From April 1976 until October 1978, the group claimed eight successful bombings and one attempt in Massachusetts. The eight men were eventually captured and sent to prison.

1980s and 1990s

The 1980s saw the deepening of the FBI’s emphasis on law enforcement partnerships. In June 1983, the Boston Division formed its first Drug Task Force. In April 1986, the division spearheaded the creation of the New England Terrorist Task Force in cooperation with the Boston Police Department; the Cambridge Police Department; and the state police departments of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Maine. Other task forces were created and quickly became effective tools for combining the skills and strengths of New England law enforcement. These task forces remain a vital force today.

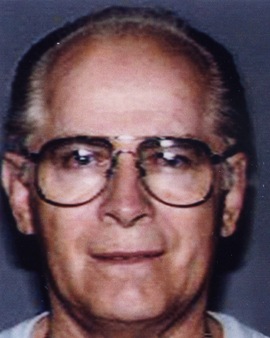

James “Whitey” Bulger

In the 1980s and 1990s, the division continued to disrupt organized crime, thanks to laws like the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act that allowed major cases to be built against the leadership of the mob for the first time.

In February 1986, after years of diligent investigation by Boston agents, Gennaro Anguilo—the Boston chief of the La Cosa Nostra (LCN) organized crime syndicate—and two of his brothers were convicted of racketeering. In October 1989, the division was able to install listening devices in the home of a major Providence, Rhode Island mob boss. The “bug” allowed them to record an entire mob induction ceremony, exposing the inner workings of the New England mafia like never before. These and other cases severely crippled the Boston branch of LCN.

One element of these organized crime investigations involved the relationship of James J. “Whitey” Bulger and the Boston Division. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, Bulger—a major organized crime figure from South Boston—provided information to the Boston FBI, some of which dealt with mob activities. On January 10, 1995, he was indicted for violations of the RICO statute, including his activities while working as an FBI informant. Bulger fled Boston to avoid arrest and was placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list in 1999. In September 2000, he was indicted for additional crimes, including participation in the murders of 19 individuals. He was arrested on June 22, 2011 and convicted of murder and other charges and sentenced to prison in 2013.

In 1990, the Boston Division was once again faced with solving a famous heist. On March 13 of that year, two men posing as Boston police officers gained access into the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Once inside, they overpowered security guards and removed 13 works of art from the museum over the next 81 minutes. The stolen artwork was estimated to be worth as much as $500 million, making it the largest property crime in U.S. history. The pursuit of this theft and other art crimes in the area has been a key focus of the division since then.

By the mid 1990s, the Boston office had moved to its current location at One Center Plaza in the Government Center section of Boston. At that time, the office employed over 300 employees; was averaging more than 6,000 criminal, security, and applicant investigations per year; and was supervising 11 satellite offices, or resident agencies.

As the Boston Division was preparing for possible disruptions to computer systems due to a feared failure of computer-driven timing devices at the start of the new millennium, its agents and evidence experts were called upon to assist with the investigation of a terrible tragedy. On the evening of October 31, 1999, Egypt Air Flight 990 bound from New York to Cairo crashed into the Atlantic Ocean south of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. The aircraft wreckage was brought to a hanger at Quonset Point, Rhode Island. There, Boston Division personnel helped the National Transportation Safety Board sift through the debris, looking for evidence to help determine the cause of the disaster. After many painstaking and sometimes harrowing hours of work, it was determined that the tragedy was neither a criminal nor terrorist incident.

Post-9/11

The attacks of 9/11 had both an immediate and lasting impact on the Boston Division, like the rest of the Bureau. Two of the hijacked flights—American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175, both of which were deliberately crashed into the World Trade Center—originated from Logan International Airport in Boston. And Mohammed Atta, the ringleader of the hijackers, had traveled to Logan Airport via a connecting flight from Portland, Maine. Following up on these links kept the Boston Division’s agents extremely busy well into 2002.

Boston personnel examine the recovered wreckage of the Egypt Air crash.

Meanwhile, in December 2001, Richard Reid attempted to destroy American Airlines Flight 63 while it was traveling from Paris to Miami. His attempts to ignite a bomb in his shoe were thwarted by alert passengers, and the flight was diverted to Boston’s Logan International Airport. Boston agents took Reid into custody and conducted an extensive investigation into his actions and possible ties to the 9/11 bombers. In January 2003, he was found guilty of terrorism and sentenced to life in prison.

In April 2012, following another investigation by Boston’s Joint Terrorism Task Force, Tarek Mehanna from Sudbury, Massachusetts was sentenced to 17 years in federal prison on terrorism-related charges. Following an eight-week trial, Mehanna was convicted of conspiracy to provide material support to al Qaeda, providing material support to terrorists, conspiracy to commit murder in a foreign country, conspiracy to make false statements to the FBI, and two counts of making false statements. According to testimony at trial, Mehanna and his co-conspirators discussed their desire to participate in violent jihad against American interests and their desire to die on the battlefield.

Seven months later, Rezwan Ferdaus was also sentenced to 17 years in prison for plotting an attack on the Pentagon and U.S. Capitol and for attempting to provide detonation devices to terrorists. Born in Ashland, Massachusetts, thousands of miles away from al Qaeda’s base, the 31-year-old used his physics degree in an attempt to craft planes strapped with explosives, which he later supplied to undercover FBI agents.

Terrorists struck at the heart of the division, this time on Patriots’ Day, April 15, 2013, when runners from all around the world set their watches and goals on the Boston Marathon finish line. As crowds of spectators were cheering the runners on, two self-radicalized brothers, Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev, executed the first terrorist attack on American soil since 9/11 by placing IEDs among the crowd. The brothers detonated the bombs seconds apart, killing three people and maiming and injuring many more and forcing a premature end to the race. Days later, on April 18, 2013, the brothers—armed with five IEDs, a Ruger P95 semi-automatic handgun, ammunition, a machete, and a hunting knife—drove their Honda Civic to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) campus, where they shot and killed MIT Police Officer Sean Collier and attempted to steal his service weapon. Following a five-day manhunt that culminated in a shoot-out with police in Watertown, Tamerlan Tsarnaev was killed, and his younger brother Dzhokhar was taken into custody after hiding out in a boat. He was charged with use of a weapon of mass destruction resulting in death and conspiracy along with 29 additional terrorism related charges. Tsarnaev was convicted and formally sentenced to death in June 2015.

Today, the Boston Division employs approximately 600 agents and professional staff and supervises 10 resident agencies across Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Maine. In line with the FBI’s focus, Boston has made counterterrorism, cyber, and intelligence operations its top priorities through the Boston Joint Terrorism Task Force and the Boston FBI Field Intelligence Group. In other investigative matters, the Boston Division continues to successfully pursue white-collar crime cases, investigating a wide variety of Medicare and health industry fraud, mortgage fraud, and embezzlement cases. Agents also avidly pursue child predators and pornographers who use the Internet to target their victims and organized crime figures who commit all manner of crimes. The Violent Crimes Task Force goes after serial bank robbers like the U30 Bandit, and the Safe Streets Gang Task Force continues to dismantle violent gangs in cities across New England.