FBI Birmingham History

Early 1900s

From its earliest days, the Bureau has had special agents and professional support staff working in Birmingham and the state of Alabama.

In 1909, for instance, agents investigated the crime of peonage (coerced labor) in the Birmingham area, working to enforce some of our nation’s first civil rights laws. In one case, they developed strong evidence that the operator of a saw mill was forcing people work illegally, but twice a grand jury of the day refused to issue indictments. More successfully, agents pursued bankruptcy frauds, including one involving jewelry businesses that led to the arrest of 19 people.

In 1919, the FBI’s office in Birmingham consisted of only three agents and a stenographer. When its workload dwindled, the office was closed in May 1925, with its responsibilities being assumed by our Atlanta Division.

1930s

By 1930, more casework was originating in and around Birmingham than Atlanta. As a result, in May of that year, the Atlanta office was closed and Birmingham was reopened, headed by former Atlanta Special Agent in Charge Reed Vetterli. The Birmingham office has been in continuous operation ever since.

At that time, the division was housed in Room 201 of the Pioneer Building in Birmingham. Its territory included the entire state of Alabama, the Northern Judicial Districts of Georgia and Mississippi, and the Middle and Western Judicial Districts of Tennessee.

Special Agent in Charge Reed Vetterli

George “Machine Gun” Kelly

During the early 1930s, the Bureau was a small agency, largely unknown to the public. That started to change as agents began hunting down notorious gangsters across the country, ultimately becoming known as “G-men.” The Birmingham Division played a key role in the origins of that nickname. On September 25, 1933, Bureau agents in Memphis learned that wanted fugitive George “Machine Gun” Kelly and his wife were living undercover in that city. Birmingham agents provided key support in the early morning raid that led to the capture of the couple. It was during the arrest that Kelly allegedly uttered something along the lines of, “Don’t shoot, G-men, don’t shoot!” He likely never said those exact words, but the press reported it and a legend was born.

1940s and 1950s

With the onset of World War II in 1939 and America’s eventual entrance into the conflict, national security issues like espionage and sabotage became FBI priorities in Birmingham and nationwide. With the construction of the U.S. Army’s Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville and the eventual housing of some 16,000 prisoners of war in camps around the state, the division had plenty of work chasing down escaped war prisoners and protecting bases and industrial plants from potential attack.

The advent of the Cold War continued these and other national security concerns, although criminal investigations made up the bulk of the workload in Birmingham. In 1959, for example, the division handled 449 criminal matters but only 56 national security ones. The latter included espionage, subversion, and other issues involving Bureau intelligence work.

Beginning in the mid-1950s, the emergence of a national civil rights movement led to some of the FBI’s most important, difficult, and often controversial cases. Alabama (including our divisions in both Birmingham and Mobile) was at the epicenter of the conflict between those demanding full citizenship for African-Americans and those who favored segregation.

In December 1957, Clarence M. Kelly became the special agent in charge in Birmingham. Kelly later served as FBI Director from 1973 to 1977.

1960s

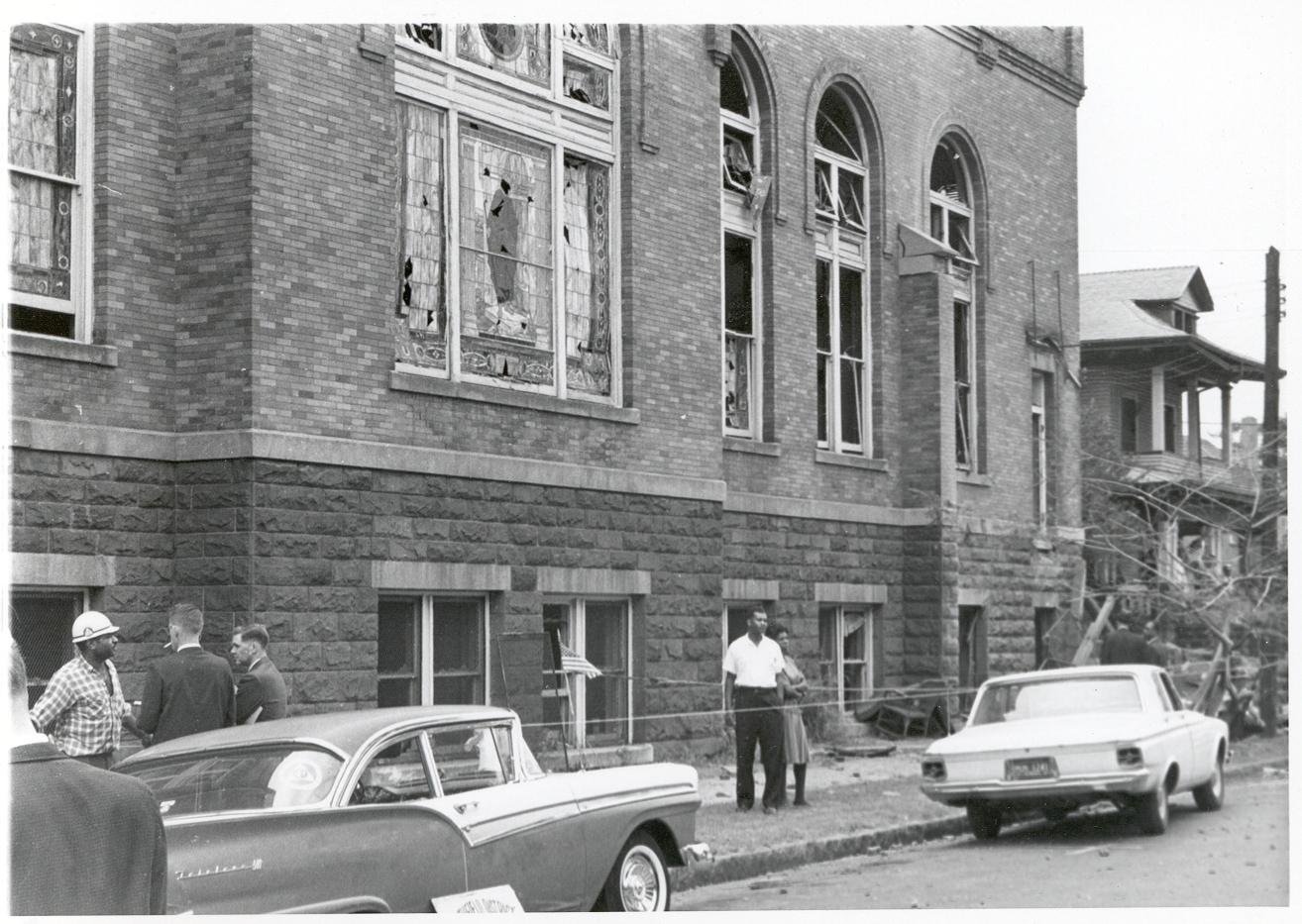

For the Birmingham Division, the most prominent investigation of the civil rights era involved the bombing of a church on a Sunday morning in 1963. On September 15, a bomb exploded at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing four young African-American girls: Denise McNair, 11, and Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, and Addie Mae Collins, each 14. The crime shocked the nation, and the Bureau’s response was immediate. The Birmingham Division launched an exhaustive investigation, led by scores of agents with the help of experts from the FBI Laboratory and others from around the country. Within a few weeks, the division had a list of suspects, but developing a prosecutable case at the time proved difficult. The initial investigation was closed in 1972 only when it was believed that federal jurisdiction in the bombing had lapsed. Changes in laws—along with the willingness of witnesses to finally testify—led to the reopening of the case at the state level in the late 1970s and at the federal level in the late 1990s. The Birmingham office helped develop new evidence in the case, resulting in the eventual prosecution of Thomas Blanton, Jr. in 2001 and Bobby Frank Cherry in 2002.

Baptist Church Bombing in 1963

The murder of civil rights activist Mrs. Viola Liuzzo, of Detroit, Michigan, was another Birmingham case that reverberated across the nation. In March 1965, Liuzzo, who was white, and Leroy Morton, an African-American man, attended a voting rights rally with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and were driving back from dropping off fellow demonstrators when they were forced off the road by a car containing several members of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), who shot at them. Liuzzo was killed; Morton was hurt but survived. Three men—Eugene Thomas, Collie Leroy Wilkins, Jr., and William Orville Eaton—were quickly identified and arrested for the crime. All three were charged with murder, but acquitted in state court. Eventually, they were each found guilty of civil rights violations in a district court in Montgomery and sentenced to 10 years in prison (Eaton died before going to jail). The role of an FBI informant in the case has led to criticism of both the informant (who was in the car with the three Klansmen who killed Liuzzo) and the Bureau’s handling of him.

1970s and 1980s

The FBI’s work against the Klan and other subversive groups continued into the 1970s and 1980s, following new Attorney General Guidelines issued in 1976. In 1979, FBI Director William Webster told a reporter, “We have investigated specific klaverns (KKK groups) that have engaged in, planned, or plotted acts of forceful violence, and we have had indictments in Alabama and elsewhere.” In 1985, Birmingham agents investigated members of a white supremacist group known as the Aryan Nation for committing robbery. That year, the division also joined FBI offices in New York, Newark, and New Orleans in helping to break up a plot to assassinate visiting Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.

One of the largest cases in division history came in December 1989, when a federal appeals judge named Robert Vance was killed by a mail bomb at his home in Mountain Brook, just east of Birmingham. Extensive investigation by Birmingham and other FBI offices pinpointed the culprit—Walter Leroy Moody, Jr., who had been sentenced by Vance years earlier and wanted revenge. In June 1991, Moody was convicted of the murder and sentenced to life in prison.

During this time period, the division also tackled a number of other types of cases, including the conviction of several local officials on bribery charges in 1987, as well as cases involving espionage, white-collar fraud, drug trafficking, and organized crime. In 1991, the Birmingham SWAT team joined other FBI and Bureau of Prisons personnel in rescuing nine hostages held by Cuban inmates in the Talladega federal prison in Alabama. None of the hostages were harmed by the prisoners, who had been incarcerated following the Mariel Boatlift in 1980 and were rioting to prevent their return to Cuba.

1990s

Cooperation with law enforcement partners grew in the 1990s. In February 1992, for example, the Birmingham Division helped create a Violent Crimes and Fugitive Task Force, which combines FBI agents with officers and deputies from the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department, the Birmingham Police Department, and the Bessemer Police Department to jointly solve and stop crimes and track fugitives.

One major joint effort was the investigation of Eric Robert Rudolph. In January 1997, a bomb exploded at a Birmingham family planning clinic, killing an off-duty police officer and critically injuring a nurse. FBI investigators ultimately tied the crime to Rudolph, the same person who had set off a bomb during the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta and launched other attacks. Birmingham agents and local police assisted in the multi-state hunt for Rudolph that ultimately led to his capture in 2003 in North Carolina.

Birmingham agents also investigated various white-collar crimes. In November 1999, for instance, the former vice president of the Citizens Bank in Fayette pled guilty to a fraud and embezzlement scheme; he was sentenced to nine years in prison and ordered to pay $12 million in restitution to the bank. In separate trials in September and October 2000, Jimmie Turquitt and his brother, Isom Turquitt, were convicted of taking out insurance policies on drug or alcohol addicted employees and then reaping thousands of dollars in benefits.

Post-9/11

The events of 9/11 led to a stronger focus—in Birmingham and nationwide—on preventing and solving acts of terror and improving intelligence capabilities, leading to far-reaching changes in the FBI.

In Birmingham, the North Alabama Joint Terrorism Task Force was officially created in April 2002 to leverage the resources and skills of the FBI and many partner agencies. A Field Intelligence Group was established the following year. These improvements paid off in 2004, when the task force prevented a potential act of domestic terrorism by arresting two men for possessing pipe bombs and a variety of weapons and anti-government literature (including a photograph of the Birmingham health care clinic bombed by Rudolph). Both men pled guilty to various charges.

Meanwhile, the office continued to handle a full load of criminal responsibilities. Its investigation of the racial profiling of Hispanic males—resulting in improper traffic stops and unlawful arrests—led to five Boaz police officers being convicted and sentenced to jail, the last in 2002. In March 2003, Birmingham agents searched the corporate headquarters of HealthSouth—once the nation’s largest provider of various outpatient healthcare services—leading to guilty pleas by 11 of its executives. In September 2007, the Birmingham special agent in charge announced more than 350 arrests in a multi-agency investigation called “Operation Clean Sweep,” which targeted violent offenders and drug felons in five counties across northeastern Alabama. In December 2008, an investigation by the FBI and its partners led to the indictment of the Birmingham mayor Larry Langford and others on a variety of bribery, fraud, and conspiracy charges. Langford was convicted in October 2009 and removed from office.

With new resources and capabilities and a continuing commitment, the Birmingham Division stands ready to help protect its communities and the country from a host of national security and criminal threats in the years ahead.