FBI Albuquerque History

Early 1900s

While the Albuquerque Field Office wasn’t officially opened until 1949, the FBI’s presence in the area went back many years earlier. Since the Bureau’s beginnings in 1908, FBI personnel have investigated federal crimes in Albuquerque and the rest of the state of New Mexico. In 1910, for instance, an agent investigated the Albuquerque connection to an anti-trust violation committed by a large western meat company. In this “Beef Trust Case,” agents across the Bureau probed the ins and outs of the meat processing industry as they uncovered illegal business practices.

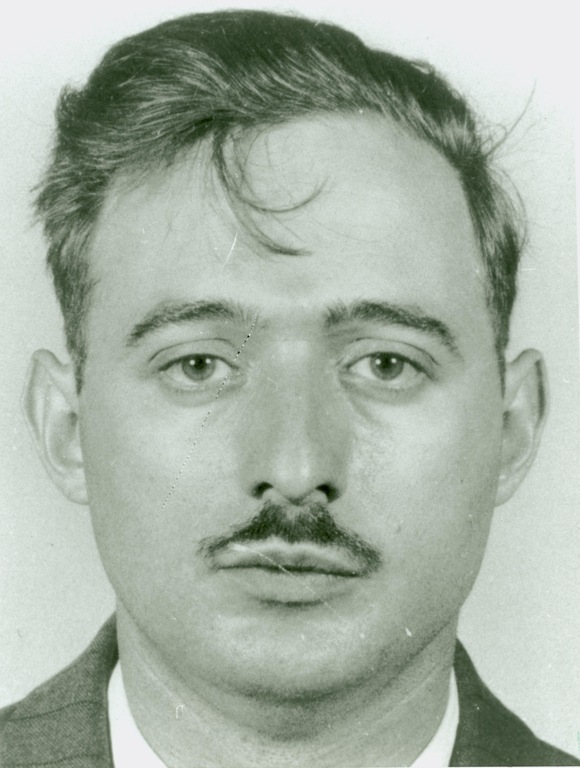

Through the 1920s and 1930s, the territory now covered by the Albuquerque Division was handled by our El Paso, Texas office. Bureau agents in New Mexico pursued car thieves and interstate traffickers in women. In one tragic case, Special Agent Truett E. Rowe died after being shot by an escaped prisoner in Gallup, New Mexico in 1937.

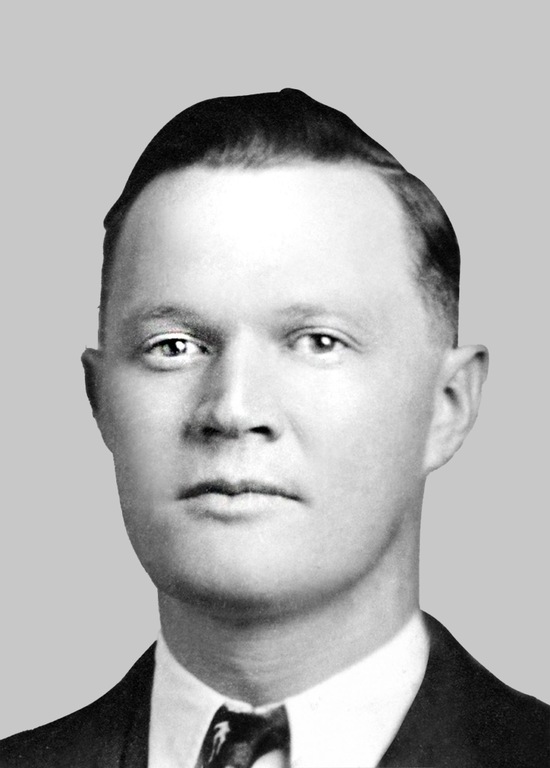

Special Agent in Charge Percy Wyly II

Special Agent Truett E. Rowe

1940s and 1950s

With the end of World War II and onset of the Cold War , Bureau operations in New Mexico became even more important. The 1946 Atomic Energy Act greatly increased the number of investigations done in and around the Los Alamos, New Mexico area because of its role in the American nuclear program. By the summer of 1949, the case load had grown so much that more than half of the El Paso Division’s investigations were in New Mexico. For that reason, FBI leadership recommended establishing a field office there. On December 12, 1949, the Albuquerque Division opened with 22 agents and five clerical staff.

Within two months, the Division had more than 500 Atomic Energy Act cases under investigation in a joint effort with the Atomic Energy Commission to ensure the security of American nuclear facilities. By 1950, it was clear that the Soviet Union had penetrated America’s nuclear program during the war. The cryptographic breakthrough known as Venona led the Bureau to Klaus Fuchs, who eventually led us to Soviet spy Julius Rosenberg and David Greenglass, who had spied for Rosenberg at the Los Alamos base. Atomic Energy Act cases remained of such importance that in 1952 an Atomic Energy Act Special Squad was formed in Albuquerque and nine special agents were assigned to it.

Julius Rosenberg

David Greenglass

Despite the focus on counterespionage in its early years, the Albuquerque Field Office remained firmly committed to maintaining civil rights and cracking down on crime in the largely rural state of New Mexico. In 1950, special agents from Albuquerque investigated the chief of the New Mexico State Police, Hubert Beasley, for violating the rights of Wesley Eugene Byrd. Thanks in large part to the aid of our agents, Beasley was later convicted.

As the state’s population grew, so did the Albuquerque Division’s workload. During fiscal year 1952, Albuquerque investigations led to 134 convictions, a substantial increase over the 89 convictions obtained the previous year. The Albuquerque Division recovered 189 stolen motor vehicles and apprehended 48 fugitives during fiscal year 1952. This trend continued throughout the 1950s, with the caseload gradually increasing year by year.

Being a rural border state, New Mexico was a prime target for fugitives fleeing from the law. In the late 1950s, the Albuquerque Division and its surrounding resident agencies (satellite offices) led the Bureau in the apprehension of fugitives crossing state boundaries in hopes of escaping capture. In July and August of 1958, for example, Albuquerque agents arrested fugitive Roy Eidson, who was sought for kidnapping; fugitive Howard Glen Livingston, who was wanted for unlawful flight to avoid confinement for highway robbery; and escaped federal prisoner Marcelino Perea Velasquez. By this time, the 38 special agents and 22 support personnel from the Albuquerque Division were closing an average of 508 cases per month, a substantial number considering their yearly operating budget was less than $600,000.

1960s

As the 1960s began, familiar challenges faced the division. The number of fugitives fleeing through New Mexico steadily increased, and the Albuquerque Division responded accordingly, making many more arrests. In one quickly resolved case, 11 prisoners, including five federal ones, escaped from the Bernalillo County jail on January 14, 1962. The Albuquerque Division initiated an immediate investigation using all agents assigned to Albuquerque. All of the escapees were apprehended within five hours. Agents and local authorities found five of the fugitives hiding on a ranch a few miles north of Albuquerque under a truck; the others were rounded up in the surrounding area.

Less than a year later, in December 1962, four more federal prisoners escaped from the Bernalillo County detention home. Twenty agents and the Albuquerque assistant special agent in charge coordinated the search for the escapees using the same tactics they had put to efficient use earlier in the year. Approximately 30 minutes after the search was launched, one of the subjects voluntarily surrendered and provided information that resulted in the apprehension of the remaining escapees.

As the 1960s came to a close, the office began to handle more high-profile cases. For example, in July 1969, agents arrested Robert Bolivar DePugh—the acknowledged leader of the Minutemen, a radical right wing group—and one of his assistants, Walter Patrick Peyson, near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. The men were arrested on warrants issued in connection with their involvement in a bank robbery conspiracy in Seattle. The men had planned to rob four Washington state banks to finance their anti-communist activities. Albuquerque agents initiated a three-day search of DePugh’s hideout and the surrounding area in Williamsburg, New Mexico, finding bombs, hand grenades, 600 pounds of dynamite, and 48 guns. DePugh was ultimately convicted and sentenced to 10 years in jail.

1970s

The work of the Albuquerque Division and New Mexico’s state and local authorities made the state less hospitable to fugitives fleeing other jurisdictions. In the 1970s, violent crime—especially on Indian reservations—became a focus of the division. In August 1970, for instance, the body of Robert Lee Begay, a Navajo Indian, was located on the Navajo Indian Reservation, which covered parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Colorado. He had been shot in the head and killed during the commission of an armed robbery. The Albuquerque Division initiated investigation. A few days later, information was received that two suspects were in Winslow, Arizona. Because that city was closer to Albuquerque’s Gallup Resident Agency than to the Phoenix Division, Gallup agents interviewed the suspects, Kyle Scribner and Ascension Leza, who were later tried for the murder. U.S. Attorney Victor Ortega commented that the case was “the best investigated murder case” that he had ever prosecuted.

In another serious case, the Albuquerque Division made the most of a lucky break. In November 1972, a four-year-old girl was abducted from a relative’s home. Soon after the kidnapping, someone dialed a wrong number, and victim answered the telephone. The caller, realizing help was needed, immediately contacted the telephone company. By keeping an open line on the telephone and using sirens on Bureau cars to establish the child’s whereabouts, the Albuquerque Division quickly located the girl.

Alert agents took advantage of another break in September 1973 to apprehend fugitive William Paul Soza. Soza had been indicted on May 18, 1973 for interstate automobile theft. While eating lunch at an Albuquerque restaurant, agents observed Soza walking past. Although they had not seen a photograph of him for several months, he was immediately recognized and arrested.

Kidnappings, robberies, and extortion continued to increase the division’s caseload throughout the 1970s. In a 1974 case, two unknown men robbed the managers of the Liberty Motel in Milan, New Mexico at gunpoint and kidnapped the managers, releasing one and raping the other one. The Albuquerque Division’s investigation and coordination resulted in the arrests of subjects Lawrence Michael Librick and Gary Ray Poindexter by a Missouri State patrolman near Lebanon, Missouri. Another Albuquerque Division investigation that year led to the perpetrators of the kidnapping/extortion plot.

Although these kidnapping and robbery cases were reactive, the Albuquerque Division also sought to be proactive in shutting down other crimes. Operation FIESTA was launched on November 1, 1976 as a joint operation of the Albuquerque Police Department, the New Mexico Governor’s Commission on Organized Crime Prevention, and the Albuquerque Division. FIESTA targeted people involved in fencing operations in New Mexico and was funded by a grant from the now-defunct Law Enforcement Assistance Administration. By December 6, 1977, 98 subjects had been identified, and 79 of them had been arrested. Property totaling $747,778.87 was recovered and returned to theft victims.

On July 10, 1979, four armed men entered the caves at Carlsbad Caverns National Park in Carlsbad and fired their weapons sporadically, taking a park employee hostage. A total of 105 visitors were trapped. The captors demanded $1 million in ransom and passage to Brazil, as well as the opportunity to talk with a newspaper reporter to gain national publicity. Arriving at the scene, Special Agent Ronald M. Hoatson of the Roswell Resident Agency assumed control of the situation. Hoatson established a rapport with one of the captors, and within 25 minutes had negotiated the release of the park employee and a newspaper reporter who had been taken hostage. Two hours after Hoatson’s arrival, all four men surrendered without incident.

The Albuquerque Division worked closely with state and local police in a number of training matters throughout the decade. In the mid-1970s, for example, then FBI Director Kelley commended the division for its participation in the FBI Police Training Program. During fiscal year 1976, the division also conducted 142 police training schools, providing 1,124 hours of instruction to nearly 4,000 officers.

1980s and 1990s

Political corruption and white-collar crime became important concerns in the early 1980s. In December 1980, the division established a White Collar/Public Corruption “hot line.” In 1984, the division was commended for its investigations into electoral fraud that led to a conviction and into an earlier scandal involving the receipt of improper gifts and conspiracy by regulated lenders.

Violent crime also remained a serious concern, especially in Indian Country. On June 10, 1980, for example, Thomas L. Cullison was found murdered in his mobile home on the Navajo Indian Reservation in Chinle, Arizona. Investigation by the Albuquerque Division determined that he had been the victim of a contract murder. Albuquerque agents quickly identified and arrested the killer.

A second murder case occurred just a few months later, when Libyan exchange student Faisal Abdulaze Zagallai was shot at least twice in the head with a .22 caliber weapon in his residence. America’s tense relations with Libya at the time meant there was an added complexity to the murder. By tracing a .22 caliber weapon recovered at the scene of the crime, the Albuquerque Division was able to identify the killer, Eugene Aloys Tafoya, and arrested him on April 22, 1981 in Truth or Consequences. While searching Tafoya’s residence, Albuquerque personnel found materials that provided strong intelligence about Libyan terrorist networks in the U.S. and abroad.

In 1983, the division conducted a week-long field training exercise, EQUUS RED, bringing together more than 400 officials from local, county, state, and federal agencies within the Albuquerque Division’s territory. The purpose of the exercise was to standardize training and unify the collective efforts of all law enforcement entities in the region.

That was not the only major cooperative venture pursued by the division. In December 1984, Operation TRUSTOP was initiated in conjunction with the Albuquerque Police Department. This joint undercover investigation resulted in 15 people being convicted in state court for vehicle theft offenses. Eleven additional people were charged in U.S. District Court, with nine of the violations involving theft from interstate shipment, interstate transportation of stolen motor vehicles, and/or interstate transportation of stolen property. All of these charges resulted in guilty pleas or successful prosecutions, and property totaling $2.3 million was recovered. Intelligence developed during this undercover operation resulted in the arrest of two additional FBI fugitives and six local fugitives.

In the late 1980s, the Albuquerque Division was instrumental in the arrests of three Top Ten Most Wanted fugitives. Albuquerque investigations contributed to the arrests of Terry Lee Connor in Chicago, Illinois; Joseph William Dougherty in San Francisco, California; and Ronald Glyn Triplett in Tempe, Arizona.

Other work of the division was also successful. In the late 1980s, a massive investigation known as Operation ILLWIND was undertaken by numerous FBI offices, including the Albuquerque Division. This FBI probe delved into widespread corruption in Department of Defense procurement, leading to indictments of government officials and private contractors for fraud and bribery in 12 states, including New Mexico and the District of Columbia.

Although violent and white-collar crime had been top priorities of the division in the 1980s, national security issues remained crucial to its work. In 1985, for example, Albuquerque agents arrested Gregory Lane Pierce, a member of the white supremacist group known as “The Order.” Agents apprehended Pierce as he retrieved vehicles left at a storage facility left by other members who had fled from a deadly a gun battle with the FBI in December 1984. The group’s members had traveled through New Mexico in search of a new base for their operations.

The Albuquerque Division was also responsible for the early 1990s investigation of Wen Ho Lee, a scientist at the Los Alamos weapons labs. Lee pled guilty to the misuse of classified information, but wider suspicions that he had given nuclear information to the People’s Republic of China were not proven. The FBI was strongly criticized for the investigation.

A special agent overlooks the Shiprock land formation on the Navajo Nation in New Mexico.

Post 9/11

Following the events of 9/11, the Albuquerque Division joined the entire FBI in making preventing terrorist attacks its top priority while still focusing on other major national security and criminal investigations.

One of the division’s more recent cases resulted in the capture of Michael Paul Astorga in 2006. Astorga was profiled on the television series America’s Most Wanted for his alleged involvement in the murder of Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Deputy James Frances McGrane, Jr. Shortly after the broadcast, Astorga was placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. Approximately 30 hours later, he was captured in Mexico after a tireless investigation by local, state, and federal law enforcement that alerted Mexican authorities that Astorga was in their area. After several hours of negotiations, Astorga was released to FBI agents. This case is a good example of the growing law enforcement cooperation between the U.S. and Mexico.

In keeping with the FBI’s mission, the Albuquerque Division has proudly helped protect local communities and the nation for decades. For more information on Albuquerque and the Bureau over the years, please visit the FBI History website.