FBI Albany History

Early 1900s

Special agents have been stationed in Albany since the FBI’s earliest years. The first known reference to the Albany office in FBI files is a 1918 document mentioning Special Agent Nelson Boyd. By 1922, Albany was operating as a full division led by Special Agent in Charge P.J. Sullivan.

Like many early field offices, Albany handled investigations of white slavery (human trafficking and interstate prostitution); peonage (forced labor); and white-collar crimes such as land and bank fraud.

The Albany Division closed in 1925 and became a resident agency of the New York Division. The office reopened on December 13, 1939 as the FBI ramped up its operations following the outbreak of World War II in Europe. At the time, its territory included eastern New York (except the New York City metropolitan area) as well as Vermont. The division has been in continuous operation ever since.

1940s and 1950s

During the 1940s and 1950s, the Albany Division investigated numerous national security matters. By 1945, it was clear the Soviet Union had uncovered many of America’s secrets during World War II. Albany was deeply involved in one of the largest espionage cases of the early Cold War years—the investigation of the Rosenberg spy ring. In June 1950, Albany agents arrested chemical technician Alfred Dean Slack. Slack had passed secrets about the composition of powerful explosives that he worked with during the war to Harry Gold, a Philadelphia chemist who was working with Rosenberg. Slack later pled guilty.

The Albany Division headquarters was located near Watervliet, a major center for the manufacture of U.S. Army guns and General Electric (GE) airplane parts and motors. At that time, GE was considered a prime target for Soviet espionage and Communist Party infiltration.

During this time, the division also began cracking down on mobsters. One major breakthrough came in November 1957 in Apalachin, a small town west of Binghamton, where soft drink bottler Joe Barbara was hosting a barbecue. The get-together’s purpose was supposedly a “soft drink convention,” but New York State Police became suspicious, since criminals had been known to congregate at Barbara’s house. Police arrived at the scene and began recording the license plate numbers of automobiles parked in the driveway. Guests noticed the law enforcement presence and started fleeing rapidly in their luxury cars or simply running into the woods. A police roadblock was quickly set up, and it was determined that the guests were representatives from several Mafia, or La Cosa Nostra (LCN), families.

This New York State Police discovery brought national exposure to the conspiratorial network of criminal enterprises known as the Mafia. This, in turn, led the Albany Division and other FBI offices to begin gathering a wealth of information on organized crime. The passage of federal gambling laws and other measures helped Albany and the rest of the FBI tackle the LCN, but it wasn’t until the passage of the Omnibus Crime Control Act of 1968 and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act of 1970 that the Bureau was able to establish links between various groups and take down entire Mafia families.

1960s and 1970s

During the early 1960s, Albany continued to investigate many matters, especially bank robberies and extortion. Albany, like the rest of the nation, also witnessed an increase in racial tension and anti-Vietnam demonstrations. Much of the division’s territory borders Canada, so Albany saw an increase in Selective Service Act violation cases as draft deserters fled north.

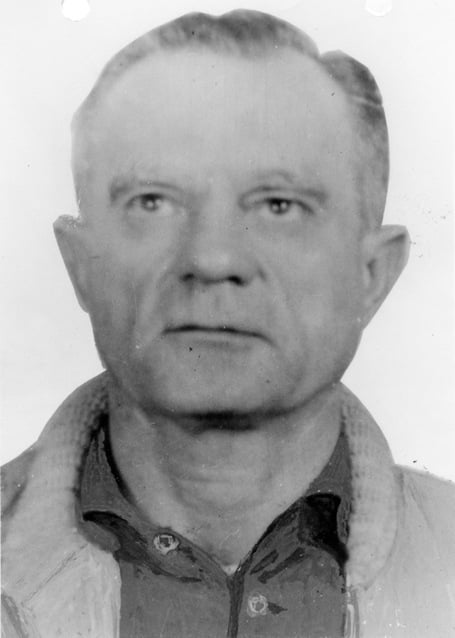

The division also pursued a wide variety of other fugitives. In November 1962, an alert Vermont postmaster informed FBI Albany that he thought he had seen David Stanley Jacubanis, who had been added to the Top Ten Most Wanted fugitives list only eight days earlier (before). Jacubanis was wanted for armed robbery, and the postmaster suspected he was residing in East Arlington, Vermont using an alias. Following the tip, Albany agents surrounded and arrested Jacubanis.

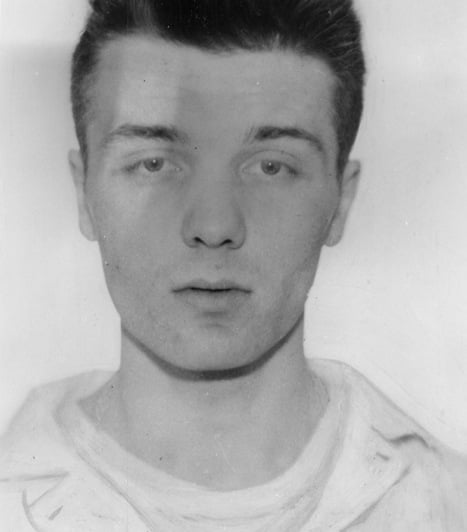

A few months later, Albany was instrumental in capturing a second Top Tenner—Jerry Clarence Rush. In 1962, Rush had escaped from a Maryland penitentiary, where he was serving time for assault with intent to murder and bank robbery. Following his escape, he met and married a stripper. Albany agents developed a rapport with the family of Rush’s new wife, gathering clues on her whereabouts. These clues led the New York Division to apprehend Rush’s wife and enabled the Miami Division to nab Rush in March 1963.

David Stanley Jacubanis

Jerry Clarence Rush

Successful fugitive investigations continued into the 1970s. Albany captured another notorious fugitive in 1973. Acting on a tip from the Buffalo Division, Albany agents conducted an exhaustive search for Charles Myrtetus, who was wanted for the kidnapping, rape, assault, and robbery of a young woman. Myrtetus had been avoiding capture, relocating from hotel to hotel; however, the division’s diligent legwork—going door-to-door between residences and hotels—led them to the Utica hotel where Myrtetus was arrested. He was later sentenced for the rape in Onondaga County. Albany also successfully apprehended fugitive Ralph Murrell in Saratoga Springs, New York in 1977. Murrell had managed to evade law enforcement since being convicted of murder 10 years earlier.

Albany’s investigations of organized crime continued as well, building on more than a decade of criminal intelligence and investigative work. Investigations led to large and small successes against the Maggadino family, whose members ran a Syracuse gambling racket; Bufalino family members, who ran a large sports bookmaking operation out of a Binghamton restaurant; and numerous other LCN members residing in Utica and Binghamton, New York. Albany also assisted other divisions in the massive investigation of the Mafia’s infiltration of the International Brotherhood of the Teamsters. Along with organized crime, foreign counterintelligence and white-collar crime continued to be top priorities in the Albany Division during the 1970s.

1980s and 1990s

In 1980, the Olympic Winter Games were held in the Albany Division’s territory in Lake Placid, New York. Albany had started international liaison and preparations for security during the games three years earlier. These were the first Olympic Games in the U.S. since the murder of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Summer Games at Munich made security a top priority for Olympic events. The division expertly handled numerous security incidents, allegations that a Soviet athlete intended to defect, and the threat that the terrorist group Omega 7 might target the games. FBI Director William Webster praised division personnel for their outstanding work.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the Albany Division investigated several large narcotics matters linked to gang activity or organized crime. In the mid-1980s, in cooperation with the New York State Police, the division launched the WATERFALL case to investigate the importation of cocaine and methamphetamine into the U.S. from Canada. Dominican and Colombian importers selling cocaine in Binghamton were targeted in the late 1990s case known as OPERATION SNOWSWEEP. Albany, participating as a member of the Oneida County Drug Task Force, also helped dismantle the “Jamaican Rick” cocaine distribution network. Subjects of other major successful narcotics investigations included James Harwood, Ronald Cheeseman, and Arthur Joyner. The Joyner case also helped solve a fire bombing that had resulted in a death.

In another case, called Pizza II—after the original Pizza connection investigation—Albany was among the eight divisions that worked with Italian law enforcement to look into the activities of Italian/U.S. criminal drug distribution networks. These networks were importing and distributing heroin from Italian drug traffickers, including the Sicilian Mafia, ‘Ndrangheta members, and Camorra members.

For decades, Albany ran an undercover investigation of the Bufalino organized crime family, which operated a wide variety of illegal operations—including counterfeit trademark and bookmaking enterprises from Binghamton. Charges brought against members of the Bufalino family during the 1990s ran the gamut from money laundering to sports bookmaking to narcotics distribution. When the case broke, the evidence was so compelling that the subjects immediately reached out with offers of cooperation, guilty pleas, and information about other crimes. The case successfully took down the huge bookmaking operation and similar operations. Albany’s actions led to indictments of high-ranking Mafia members, including a capo, a soldier, and 10 other associates.

Post 9/11

Following the events of 9/11, preventing terrorist attacks became the FBI’s top priority. In 2002, like many FBI divisions, Albany stood up a Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF), bringing together federal, state, and local agencies to tackle terrorist threats. The division also worked to develop a comprehensive approach to intelligence collection and analysis across all priorities, creating a Field Intelligence Group in October 2003.

These efforts paid off during the investigation of Albany residents Yassin M. Aref and Mohammed Hossain. Following an investigation by the Albany JTTF, both men were arrested by federal authorities in 2004. In October 2006, they were convicted of money laundering and conspiring to support a terrorist group in connection with a possible plot to kill a Pakistani diplomat. Both men were sentenced to 15 years in prison in March 2007.

In 2007, the Albany office—assisted by the JTTF, the Albany Police, the U.S. Postal Service, and the New York State Department of Correctional Services—investigated the mailing of 12 letters containing a powdery substance to media outlets, New York residents, and the division itself. Biological tests proved negative, but one letter caused a hazardous material response by several New York City departments. The investigation identified an upstate New York prison inmate as the culprit. In a separate but similar incident, Anthony Smith was sentenced to at least a dozen years in prison for sending a letter with powder to the chief justice of the New York State Court of Appeals. The letter said the enclosed substance was a deadly chemical poison.

The office also continues to handle a full load of criminal responsibilities. In one case, the division worked closely with New York State Police and the DeWitt City Police Department to investigate a man named Jerome Feldman. Feldman promised to arrange organ transplants in the Philippines for the desperately ill, but instead simply kept his victims’ money. One of his victims even died awaiting a promised liver transplant. Feldman was indicted for fraud and pled guilty in August 2009. The division also handles a wide variety of other investigations—from child pornography to extortion to public corruption.

Heading into the FBI’s second century of service, the Albany Division remains ready to help protect its communities and the country from national security and criminal threats of all kinds.