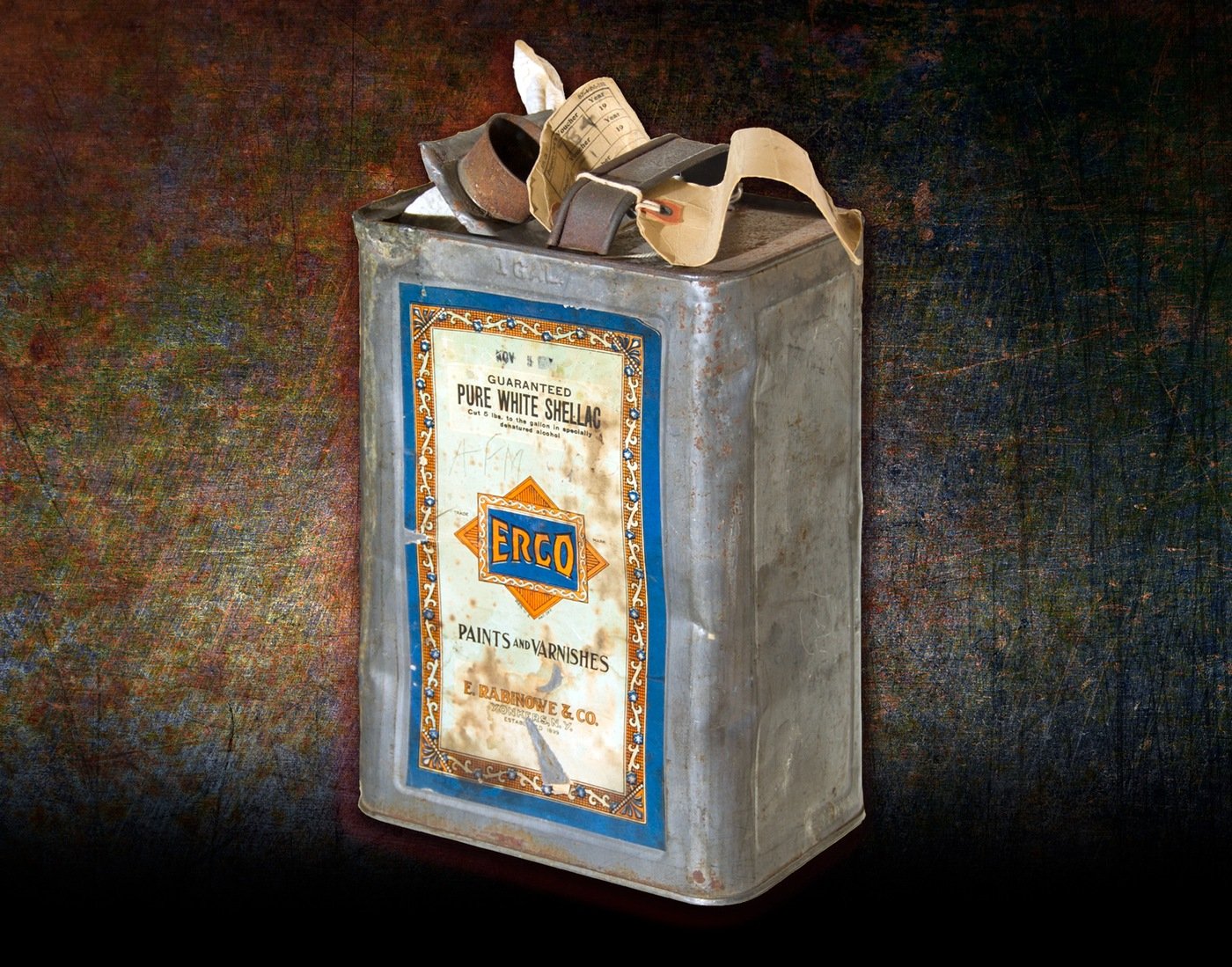

Lindbergh Kidnapping Gas Can

On September 19, 1934, Bruno Richard Hauptmann was taken into custody and was indicted for extortion a week later. His arrest brought an end to the more than two-year-long investigation into the kidnapping and murder of Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr., the 20-month old son of famous aviator Charles Lindbergh.

Charles Lindbergh, Jr. was kidnapped at about 9:00 p.m. on March 1, 1932, from the nursery on the second floor of the Lindbergh home near Hopewell, New Jersey. Lindbergh’s absence was soon discovered and, during a search of the home, a ransom note demanding $50,000 was found on the nursery window sill.

Over the course of the next month, the Lindbergh family received 12 more ransom notes and eventually ended up paying $50,000 through a go-between, Dr. Condon, to a mysterious man known only as “John.” Upon receipt of the money, “John” handed over a note containing instructions that the kidnapped child could be found on a boat named “Nellie” near Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. Two searches of the area were made, but both were unsuccessful.

On May 12, 1932, the body of the kidnapped baby was accidentally found, partly buried and badly decomposed, about 4.5 miles southeast of the Lindbergh home. The coroner’s examination showed that the child had been dead for about two months and that his death was caused by a blow on the head. Ten days later, at the order of President Herbert Hoover, the FBI offered its assistance to the investigation; the New Jersey State Police led the New Jersey component of the investigation and the New York Police Department ran the New York City component. Eventually President Roosevelt put the FBI in charge of the federal component of the investigation.

In all, the FBI covered thousands of leads across the United States. Many of those leads were false, but the net began to close when the Federal Reserve Bank of New York discovered 296 $10 gold certificates and one $20 gold certificate that were all from the same $50,000 ransom that the Lindberghs had paid to “John.” Handwriting experts examined the notes and determined that all the notes were written by the same person and that the writer was of German nationality but had spent time in America. Dr. Condon described “John” as Scandinavian and, believing he could identify him, spent considerable time viewing photographs of possible suspects and known criminals. The ladder used by the kidnapper was also painstakingly examined, and testimony by an expert on its construction later played a critical role in the trial of the kidnapper.

The break in the case came on September 15, 1934, when an alert gas station attendant received another of the ransom bills to pay for five gallons of gasoline. The gas station attendant, suspicious of the $10 gold certificate, recorded on the bill the license number of the automobile driven by the purchaser. This license number came back to identify the subject as Bruno Richard Hauptmann. Hauptmann’s house was closely surveilled by federal and local authorities until he appeared on September 19, 1934, and was promptly taken into custody.

The evidence against Hauptmann came together quickly. One of the pieces of evidence tying him to the kidnapping: a gas can, found in his garage, in which Hauptmann hid the gold certificates. The gas can is currently on display at the Newseum in Washington, D.C., in the “Inside Today’s FBI” exhibit. It is the property of the New Jersey State Police Museum and Learning Center and is a part of their collection of Lindbergh Kidnapping artifacts on loan to the Newseum.

Hauptmann’s trial began on January 3, 1935, in Flemington, New Jersey, and lasted five weeks. Tool marks on the ladder matched tools owned by Hauptmann, wood in the ladder was found to match wood used as flooring in his attic, Dr. Condon’s telephone number and address were found scrawled on a door frame inside a closet, and handwriting on the ransom notes matched samples of Hauptmann’s handwriting. On February 13, 1935, the jury returned a verdict: Hauptmann was guilty of murder in the first degree, and he was sentenced to death. A series of appeals failed to overturn the sentence, and on April 3, 1936, at 8:47 p.m., Bruno Richard Hauptmann was put to death.

The Lindbergh kidnapping happened while Congress was debating a federal kidnapping act, and the nation’s horror at the crime certainly helped the quick passage of the bill that became known as the “Lindbergh Law.” It authorized the FBI to investigate kidnappings where it was thought the victim had been taken across state lines.

Since then, the law has evolved. Today’s kidnapping law authorizes us to investigate any reported mysterious disappearance or kidnapping involving a child of “tender age”—usually 12 or younger. However, the FBI can become involved with any missing child under the age of 18 as an assisting agency to the local police department. There does not have to be a ransom demand, and the child does not have to cross the state lines or be missing for 24 hours. Research indicates the quicker the reporting of the disappearance or abduction, the more likely the successful outcome in returning the child unharmed.

Anyone with information regarding a missing child should contact your local FBI field office, your local police department, or call 911. Tips may also be submitted to the FBI through tips.fbi.gov.