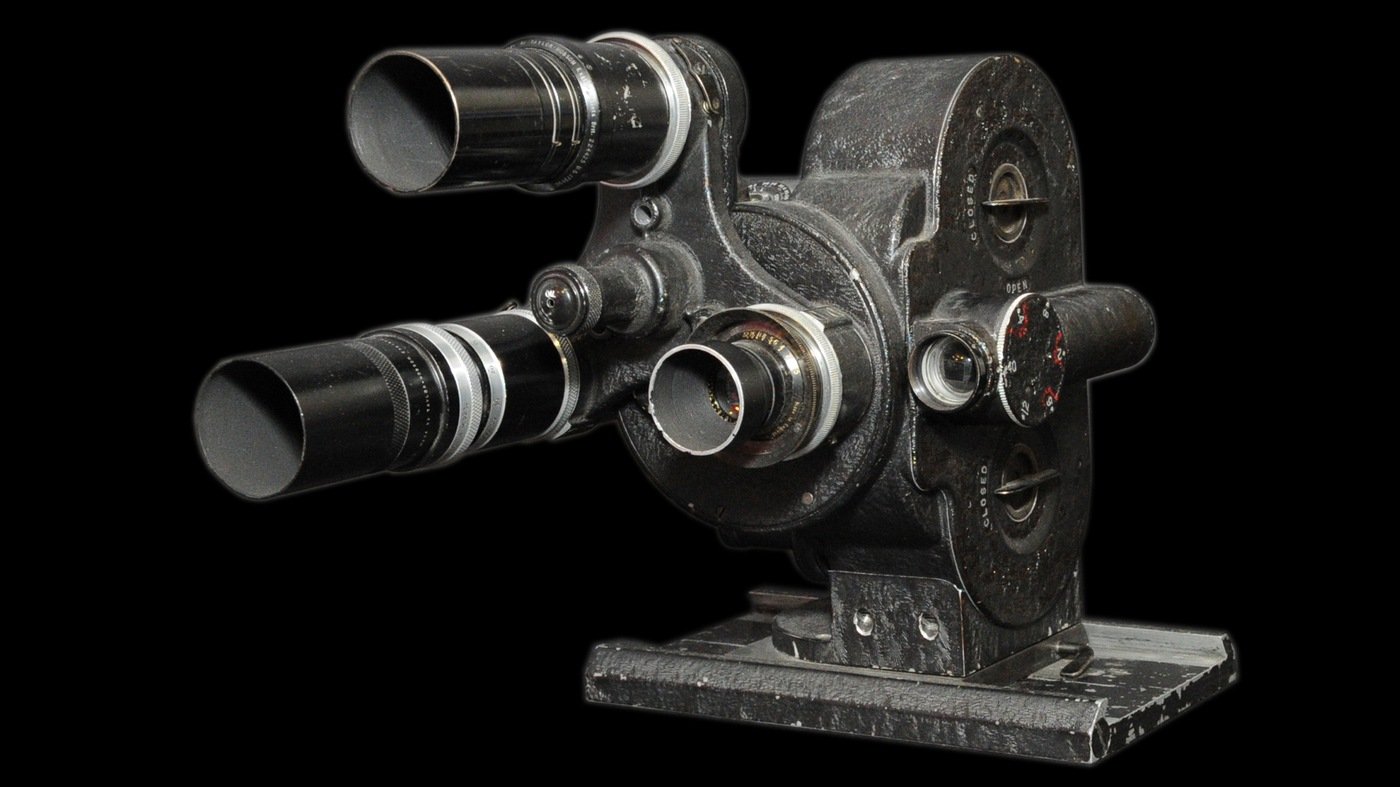

Eyemo Camera

He busted gangsters. He captured murderers. He infiltrated spy rings. He was the best “shot” President Theodore Roosevelt ever saw. His name was James E. Amos, and he was also one of the FBI’s first African-American special agents.

Amos joined the Bureau of Investigation, the FBI’s predecessor, as a special agent on August 24, 1921, with a background in investigative work and public service: He had worked in the Department of the Interior and the Customs Office prior to serving with President Theodore Roosevelt in several roles, including bodyguard, for 12 years. Following the president’s death in 1920, Amos worked as an investigator for the William J. Burns International Detective Agency.

When Burns became the fourth director of the Bureau of Investigation in 1921, Amos submitted his application for special agent—along with character references from a general, a senator, two former Cabinet secretaries, and the 26th president himself. Amos worked espionage, organized crime, and white-collar crime cases throughout the country during his historic 32-year career with the FBI. Because of his familiarity with various weapons, he also served as a firearms instructor.

Amos helped bring many criminals to justice, including the Louis “Lepke” Buchalter gang, a notorious group of professional hitmen known as Murder, Inc.; the Tri-State Gang, a band of gangsters who committed murders and robberies in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia; and Marcus Garvey, a businessman whose company defrauded African-Americans by falsely promising paid passages to Africa.

Amos also helped catch members of the Duquesne Spy Ring, a U.S.-based group of Nazi spies led by Frederick Joubert Duquesne. Because of his knowledge of New York City, Amos shadowed Duquesne.

This Eyemo 35mm film camera is similar to the one used to conduct surveillance on the Duquesne Spy Ring. FBI special agents used cameras like this one to film a series of meetings between double agent William Sebold and Nazis. Sebold was a German-American whom the German Secret Service had persuaded to spy on the United States—but Sebold ultimately served as a double agent for the U.S. He met with Nazis in a bogus office in Manhattan that had hidden microphones and a two-way mirror that enabled the Americans to secretly film the meetings.

With the acumen of agents like Amos and the help of gadgets like the Eyemo, all 33 members of the spy ring, including ringleader Duquesne, either pleaded guilty or were convicted at trial by December 1941. During the trial, Duquesne claimed he had visited President Theodore Roosevelt many times—a claim that Special Agent Amos easily disqualified. On January 2, 1942, the spies were sentenced to serve a combined total of over 300 years in prison.