Harvey’s Casino Bomb

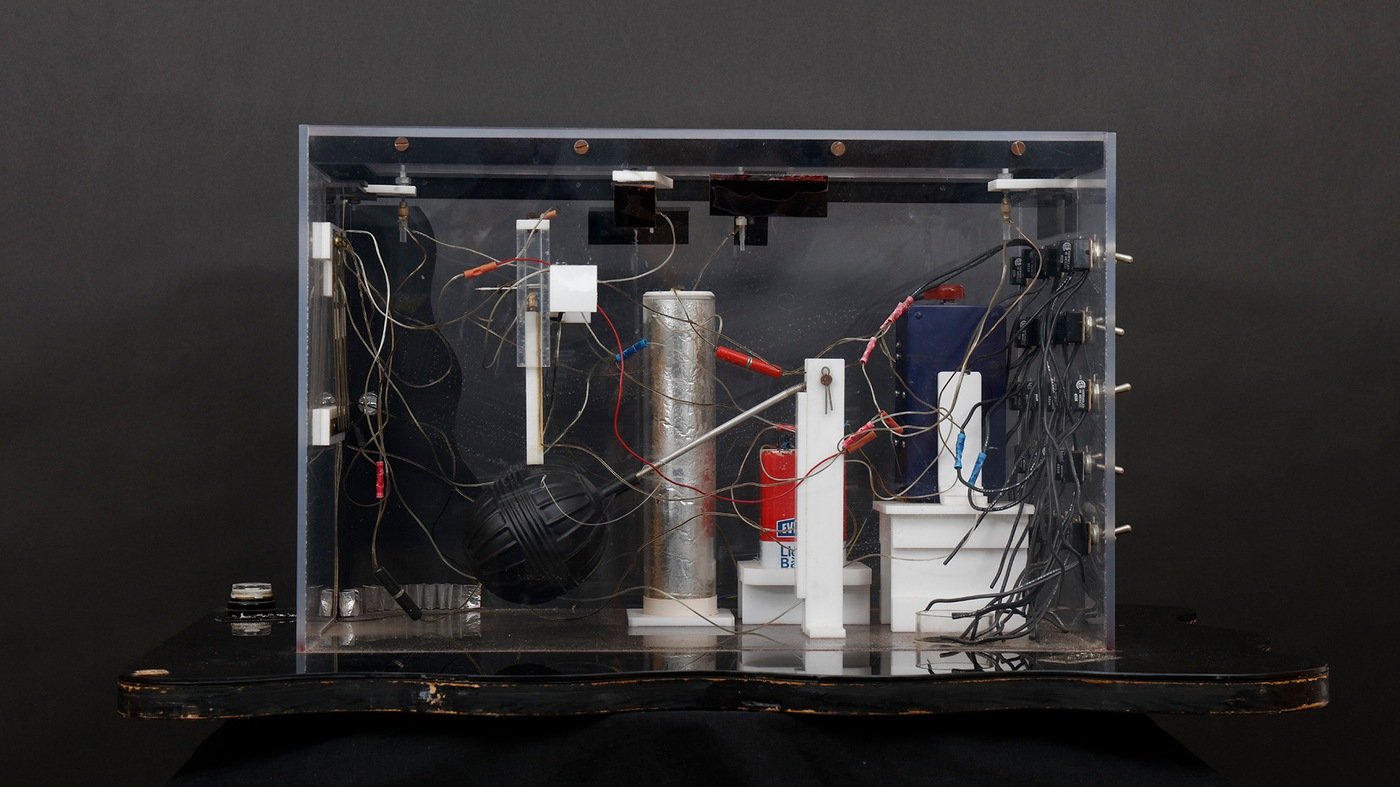

This is the trial model of Harvey’s Casino Bomb.

After 39 years, it remains one of the most unique improvised explosives devices (IEDs) the Bureau has ever come across.

The device contained nearly 1,000 pounds of dynamite and eight triggering mechanisms, which made it virtually undefeatable.

In the early morning hours of August 26, 1980, men wearing white jumpsuits and pretending to deliver an IBM copy machine rolled a bomb into Harvey’s Resort Hotel and Casino in Stateline, Nevada, near Lake Tahoe.

A note left with the bomb—titled STERN WARNING TO THE MANAGEMENT AND BOMB SQUAD—began ominously: “Do not move or tilt this bomb, because the mechanism controlling the detonators in it will set it off at a movement of less than .01 of the open end Ricter [sic] scale.”

“Do not try to take it apart,” the note went on. “The flathead screws are also attached to triggers and as much as ¼ to ¾ of a turn will cause an explosion....This bomb is so sensitive that the slightest movement either inside or outside will cause it to explode. This bomb can never be dismantled or disarmed without causing an explosion. Not even by the creator.”

The “creator,” the FBI later discovered, was 59-year-old John Birges, Sr.—who wanted $3 million in cash in return for supplying directions to disconnect two of the bomb’s three automatic timers so it could be moved to a remote area before exploding.

After being discovered, the bomb was photographed, dusted for fingerprints, X-rayed, and studied. Finally, more than 30 hours later, a plan was agreed upon: if the two boxes could be severed using a shaped charge of C4 explosive, it might disconnect the detonator wiring from the dynamite.

Harvey’s and other nearby casinos in Lake Tahoe were evacuated, and on the afternoon of August 27, the shaped charge was remotely detonated.

The plan was the best one available at the time, but it didn’t work. The bomb exploded, creating a five-story crater in the hotel.

Tourists at neighboring casinos bet on when the bomb would go off, or if it would go off. After the bomb detonated, crowds cheered and reveled from a safe distance. Due to the planning of the FBI and our partners, there were no deaths or injuries.

“Today’s IEDs use more advanced electronics,” said retired Special Agent Thomas Mohnal, a former examiner in our Explosives Unit, based at the FBI Laboratory in Quantico, Virginia. “Our techniques and tools for dealing with these devices are also more advanced,” Mohnal added, “but you still probably couldn’t build a bomb much tougher to defeat than Harvey’s.”

Birges, Sr., said to be an inveterate gambler who had lost a substantial amount of money at Harvey’s, was caught (with the help of an alert clerk at a nearby hotel who had written down the license plate of the bomb delivery van) and convicted. His two sons, charged as accomplices, were given suspended sentences because they cooperated with authorities. Birges died in jail in 1996.

Today, the FBI Laboratory displays the trial model as a “notable IED” example in its explosives reference collection.

The FBI’s partners in the investigation included the Nevada Department of Public Safety, the California State Police, the U.S. Army Explosive Ordinance Disposal, and the Nuclear Emergency Support Team.

Watch a video describing the FBI’s role in the investigation.