Millions of children log into their favorite online gaming platforms each day to battle it out with their friends, creating worlds where their imaginations can run wild. They are there to have fun. Not every ‘friend’ is real, however, and not every player is there to have fun. Sexual predators are often online with those children, and parents need to pay attention to what’s happening.

In late summer 2020, FBI New York Intelligence Analyst Chris Travis noticed several similarities in cases where sexual predators were using popular online gaming platforms to victimize children. He decided to take a deeper look at the investigations his colleague, Special Agent Pao Fisher, had recently opened. He discovered something that struck a nerve.

“As an analyst, one of my jobs is to take case information, match it to other cases to look for trends and commonalities, and to see if different suspects are using similar methods,” said Travis. “I remember when I noticed the patterns, and it hit home. My young son loves to play online games, and he was potentially being exposed to the behavior I was seeing in these cases.”

“We work so many investigations that, as a case agent, you don’t often have time to sit back and see the bigger picture before it’s on to the next investigation. That’s why working with Chris and the other intelligence analysts is so important,” said Fisher. “I apply the patterns and trends they discover into my investigations by using that knowledge in conversations with victims and in the interviews I conduct with suspects. This often allows for more detailed and pointed discussions that may have not otherwise occurred.”

Travis realized several different subjects began grooming children on the online gaming sites, initially through chats or voice communications, then talked the children into switching over to other social media applications to gain greater access to their potential victims.

Fisher interviewed multiple suspects who detailed this process. “They explained to me how they start up conversations and get to know the victims, usually by posing as a child of similar age,” Fisher said. “After a shockingly short period of time, they enticed their victims to take the chat to one of the popular social media apps. Most of the popular gaming sites don’t allow for the exchange of photos or videos. Once on the social media app, the suspect would pressure the child to send photos, getting more aggressive and demanding more compromising images. Ultimately, this led to the predator threatening to expose the victim’s photos to their parents or posting them online.”

During his research, Travis found a statistic that more than half the children in the U.S. are users of online gaming platforms—and most of those children are under the age of 16. “When I was a kid, I would watch cartoons on television. That was my form of entertainment,” Travis said. “My son is entertained by playing these games, which is great. But parents need to know there are dangerous people online, and there are ways to protect your kids.”

“My young son loves to play online games, and he was potentially being exposed to the behavior I was seeing in these cases.”

Chris Travis, intelligence analyst, FBI New York

Travis assembled all the information he amassed and wrote a summary of his findings and a detailed conclusion about how this threat can be mitigated. He then briefed his report to the head of the FBI New York Office, Assistant Director-in-Charge Bill Sweeney.

“During the meeting, we kept throwing questions at Chris, and you could tell everyone in the room felt that he hit on something very disturbing,” Sweeney said. “You think younger children, the 7-to-12 age range, are physically safe if they’re just in the other room. You don’t worry about them the same way you would a toddler or a teenager.”

Sweeney asked Travis how he would solve the problem, and he responded, “We can only get so far by speaking to small groups. We should create a bigger approach, with a public service announcement, to at least start the conversation.”

Sweeney and others in the room thought it was an important step. Going even further, Sweeney said that it had to be a whole-of-community approach. “The FBI does not have the resources to stop every predator, which is a harsh and extremely sad reality for the world we live in,” Sweeney explained. “Millions and millions of children are online in multiple ways every single day, especially since the start of COVID-19. That significantly increases their chances of being victimized. We can have an impact if we educate parents about how to lock down their children’s devices and educate children about how to be safe. We can also start a conversation with other members of the community, like pediatricians, educators, and community leaders, so everyone plays a role in stopping these predators.”

And today—after several months of brainstorming and planning around the new world of COVID-19 restrictions—FBI New York launched the It’s Not a Game campaign and debuted the public service announcement Travis believed would kick off a broader conversation.

Part of the campaign roll-out involves a panel discussion with media that includes Sweeney, several community members mentioned above as touch points in children’s lives, and Supervisory Special Agent Seamus Clarke, who leads the FBI/NYPD Joint New York Crimes Against Children and Human Trafficking Task Force.

“I worked a few cases involving crimes against children before joining the task force, but seeing the volume of cases and what these sexual predators are capable of—I was shocked,” Clarke said. “I realized I needed to practice the same cyber hygiene we preach to others, so I recently locked down my children’s devices. They weren’t pleased, but it started the conversation.”

Clarke explained ways parents can take more control of what their children can access, and who has access to them. “Practically all recent cell phones and tablets have built-in features that allow parents and guardians to have varying degrees of control over how the device is used or isn’t used by their child,” Clarke said. “Exact settings differ depending on the manufacturer, but there are generally common features devices share parents should know about. I highly suggest parents take the time to get familiar with their child’s device and ensure it is properly set up.” (See sidebar for details.)

Sweeney wants parents to understand the FBI’s message with this campaign isn’t to keep your children off online games. “As much as we want to shield our children from every evil in the world, that’s not a practical way to live,” he said. “Children are going to play these online games, and that’s okay. But we can set parameters, we can learn the security settings on our devices, and we can talk with our children, or find someone for them to talk to.”

If you believe your child may be a victim, or if you know someone who is, please reach out to the FBI at 1-800-CALL-FBI or report it online at tips.fbi.gov.

Setting Up Your Child’s Device

There are several types of parental controls you can enable on your child’s device—many of which can be tailored by age—to help protect them from online predators. Some of these settings and functions include:

- Limiting the amount of screen time (this prevents overuse of the device, limits usage to certain times, and prevents late-night access when the parents are most likely asleep and unable to monitor).

- Requesting weekly usage reports.

- Setting up age parameters so your child can only download age-appropriate apps (most apps are rated for age usage, similar to movie ratings).

- Limiting what internet content can be accessed to ensure adult websites are not viewable on the device.

- Turning off the device’s location services.

- Setting a PIN (all of these settings are usually controlled by a PIN set by a parent, so the child has no ability to alter the settings).

Note: In many peer-to-peer games and other applications, there may be an embedded chat feature that allows the user to communicate by voice and/or text with other players. This feature can usually be turned off by the parent under the settings of individual apps, and a PIN can usually be created within an app to prevent the child from changing individual app settings.

Additional Resources

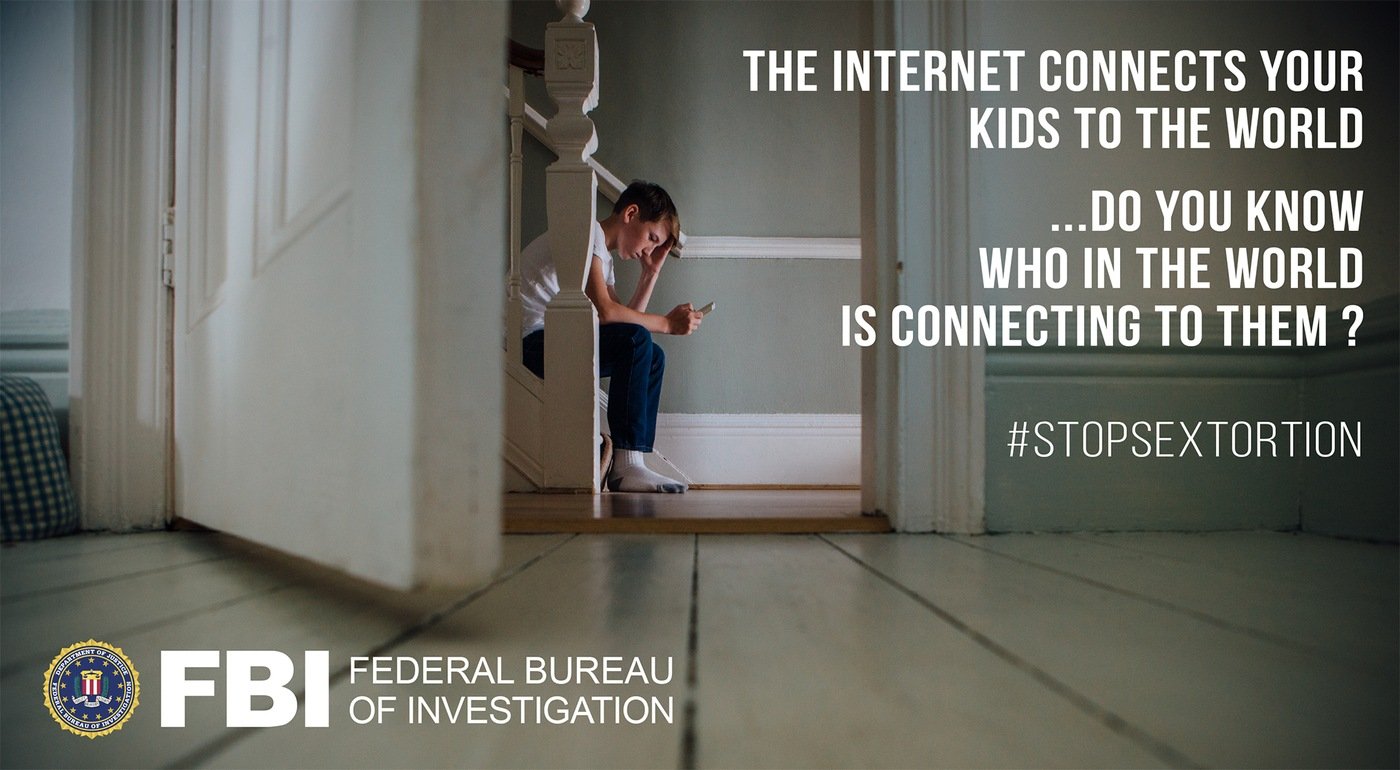

The FBI has seen a huge increase in the number of cases involving children and teens being threatened and coerced by adults into sending explicit images online—a crime called sextortion.

There are several resources available to help caregivers and young people better understand what sextortion is, how to protect against it, and how to talk about this growing and growing threat.

Learn more at fbi.gov/sextortion

Request a Speaker

Complete this form to request a speaker from the FBI to come and discuss the It's Not A Game campaign.

For Media

For members of the media, below are video clips used in the PSA without sound, as well as clips of the video games created by the FBI for this campaign. If you have any further questions or would like to request an interview, please contact the FBI New York Press Office at 212-384-2100 or by email at nyo-media@fbi.gov.