A Look Back at the Coors Kidnapping Case

Law Enforcement Collaboration and Public Assistance Played Key Role

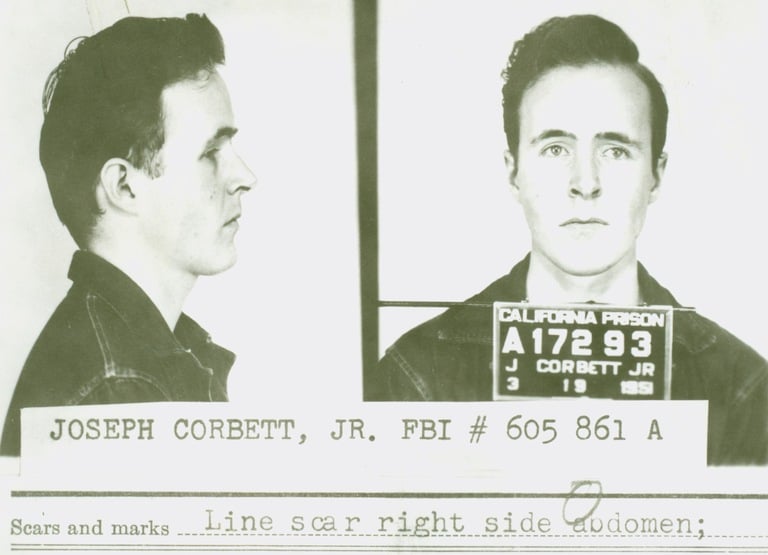

This March 19, 1951 mug shot was taken upon Joseph Corbett, Jr.’s incarceration at the California Institution for Men in Chino, California, where he was sentenced to five years after pleading guilty to second-degree murder. He escaped from prison and committed the kidnapping and murder of Adolph Coors, III while a fugitive.

On February 9, 1960, a milkman sounded his horn several times in an attempt to get the attention of the driver of a station wagon that was blocking the middle of the bridge over Turkey Creek, near Morrison, Colorado. When there was no response, he got out of his truck and walked to the vehicle—it was empty, but its engine was running and the radio playing. A few more beeps on the horn didn’t bring the driver back, so the milkman moved the car himself to the side of the road, noticing a reddish-brown stain on the bridge and a hat on the edge of the river bank below.

The milkman reported the matter to the local police, who quickly determined that the car belonged to Adolph Coors, III. Heir to the Coors Brewing Company fortune, Coors had left his house—not far from the bridge—that morning, but had not been seen since. Searchers soon spread out over the area looking for the missing 45-year-old father of four. In addition to the hat, a few objects belonging Coors were found below the bridge, but no other trace was found during the wider search.

Twenty-four hours later, the FBI’s Denver Division entered the case to help Colorado authorities—with the passage of a day since Coors’ disappearance, the federal kidnapping statute could be invoked and the full investigative resources of the Bureau could be called upon. Coors’ wife, Mary, received a typewritten note that day demanding a ransom for the return of her husband. Under the guidance of law enforcement, she followed the instructions regarding contacting the kidnapper but heard nothing back.

The FBI Laboratory began analyzing the available evidence, especially the ransom note, which had a distinct typeface and was written on paper with an uncommon watermark.

Meanwhile, state and local police pursued leads closer to the scene of the crime, conducting extensive interviews and other investigative activities. They soon focused on a canary yellow Mercury that had been seen in the area on several occasions and tried to track down its driver, a man who called himself Walter Osborne. The FBI learned that Osborne had disappeared around the time of Coors’ abduction, but before doing so had obtained a gun, handcuffs, and a typewriter. And the Bureau also learned that Osborne had obtained an insurance policy at a previous job, and that policy designated a man named Joseph Corbett as his beneficiary.

Joseph Corbett, Jr.’s FBI Wanted Poster

Corbett, in turn, had a son—Joseph Corbett, Jr.—who had previously been convicted of murder but had escaped from a California prison. Now a chief suspect in the Coors case, the FBI obtained a fugitive warrant for him and placed him on the Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list soon after.

Throughout the summer of 1960, Corbett, Jr.’s trail remained cold. But tragically, the trail leading to Adolph Coors ended on September 11, 1960, when some hikers came across a pair of trousers in the woods about 12 miles southwest of Sedalia, a town south of Denver. The pants had a key ring bearing the initials ACIII. The trousers, other items of clothing, and skeletal remains found there were determined to belong to Coors. A jacket and shirt had bullet holes that showed he had been shot in the back, and an analysis of a shoulder bone confirmed this.

The story of Coors’ disappearance remained in the public eye and was featured in various publications, including Reader’s Digest. Corbett, Jr.’s wanted photo sparked interest and leads across America, but it was the magazine’s readers in Canada who would break the case. One reader pointed the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and their FBI allies to an apartment rented by a man who resembled Corbett, Jr., but the man had recently moved on. The next day, the manager of a rooming house in Winnipeg called local police to report that a man who looked like the fugitive had recently stayed at her flophouse. She also noted that the suspect had been driving a fire engine red Pontiac.

That new information went out across Canada, and on October 29, 1960, a Vancouver police officer reported a similar vehicle parked outside of local motor inn. Soon, police—with the assistance of the FBI’s Toronto legal attaché office—were knocking on the door of the hotel room. The man who answered said, “I give up. I’m the man you want.”

Corbett, Jr. was returned to Colorado, where he was tried by the state for Coors’ murder (because Coors’ remains were found within the state, he wasn’t tried on federal kidnapping charges). During the trial, the FBI offered 23 agents, five lab examiners, and a fingerprint expert to help put forward an iron-clad case. Especially compelling was the ransom note believed to have been typed on Corbett, Jr.’s typewriter, and damning evidence taken from his burned-out canary yellow Mercury, which was recovered by law enforcement in New Jersey shortly after Coors’ disappearance. On March 19, 1961, Joseph Corbett, Jr. was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

And 65 years later, the FBI continues to offer a wide array of investigative assistance to our state and local partners—just as we continue to rely on the support of the public to help us solve crimes.